On page 1 of its Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/2067, 22 November 2016, the European Union commented in the context of the adoption of the new accounting standard for financial instruments, IFRS 9:

“The standard aims to improve the financial reporting of financial instruments by addressing concerns that arose in this area during the financial crisis. In particular, IFRS 9 responds to the G20’s call to move to a more forward-looking model for the recognition of expected losses on financial assets.”

These words particularly addressed the general political critique about the treatment of value adjustments (impairments) during the 2008 financial crisis: “too little, too late”. Banks have waited too long until they reacted, they continued with cramming loans into the housing market when there were already signs of a correction, and they didn’t feel obliged to build-up reserves for some not-so-good-later-times because they didn’t see the necessity to make early asset value adjustments. This was the purport of the statements of G20 politicians and many regulatory and supervisory bodies when analysing the accounting system after the dust of 2008 has settled. This view was also supported by many research papers, e.g. the important “Report of the Financial Stability Forum on Addressing Procyclicality in the Financial System” (2009) which found that cyclical volatility could have been reduced if banks had earlier recognised credit risks in their accounts.

The consequence to this was a radical change in accounting for loan losses in particular, or financial instruments in general. Two of the main points in this standard are a) an accelerated loss recognition on the balance sheet by focussing on “expected” loan losses as compared to the “incurred” loan losses system applied before (this means that now even credit risk deteriorations can trigger a revaluation while before only a hard credit event, e.g. non-payment, led to an adjustment), and b) the necessity to build up higher reserves for loans in general (which is basically a consequence of a) here).

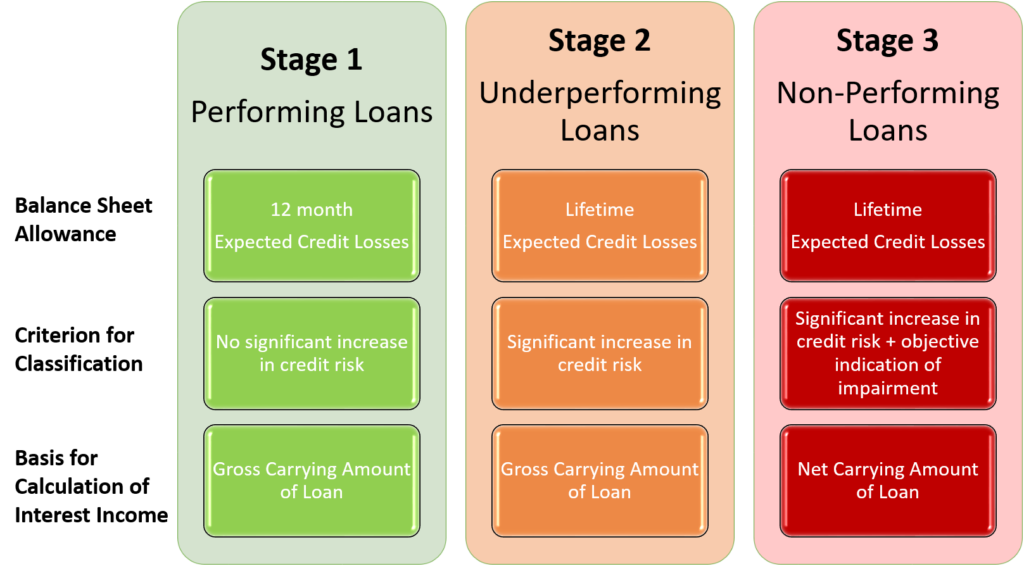

Under IFRS, the new IFRS 9 applies a 3-stage model which requires to classify loans into performing, under-performing or non-performing based on observations of credit risk movements. Each of these three stages triggers different levels of reserves (balance sheet allowances, provisions). The following graph highlights this.

Source: Own depiction according to IFRS-Foundation

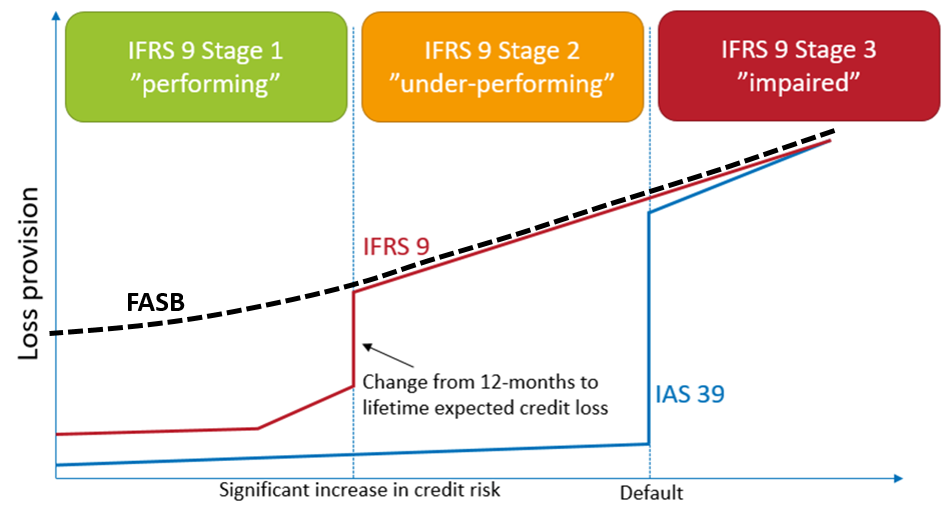

Side-comment: The rules according to US-GAAP are quite similar to IFRS 9. However, the FASB-approach does not know any different stages. It just builds reserves for each and every loan according to the lifetime expected credit losses.

The reserve building for the different stages under the FASB-approach, IFRS 9 (and as compared to the old IAS 39) is shown in the following graph.

Adjusted own depiction of the graph in Frykström/Li (2018), IFRS 9 – the new accounting standard for credit loss recognition, in: Economic Commentaries, Number 3/2018. Sveriges Riksbank.

This new approach definitely makes sense from an investors’ point of view as it is clearly more in line with a timely fair valuation of assets, which improves both transparency AND bank management’s stewardship. It also brings along more management discretion (and the risk of a loss of comparability) than under the old rules which has been sometimes criticised. But this is the normal price to be paid when moving towards a more value-oriented accounting setting. In the particular case of IFRS 9, we do not think that management’s discretion is a real big problem – at least it is certainly not nearly as problematic as in the case of goodwill impairment testing.

So far, so good! But what if you do not want to see banks as normal players of an economic system? What if you also want to see banks as something like a last resort for supporting the economy (or at least an important part of the “last resort” system). What if you want to see banks as something that has to be kept alive and working – also and in particular if there is an economic crisis? Then – depending on the kind of crisis – perhaps the new accounting standards are not the best way to support this.

The 2008 financial crisis was a banking crisis. It was fuelled by banks and it had its origin at banks. So restricting banks to more economic behaviour makes sense in order to reduce the likelihood of these kinds of crises again. Also with a view on other types of crises that are the result of a normal cyclical behaviour of an economy such value-oriented rules make sense. But in a coronavirus-type crisis, an external shock-driven crisis that has per se not its roots in some bad economic development, we rather do not want to have banks to act in a strict economic sense – which means to stop handing out loans, immediately accounting for the credit risk deterioration of existing loans and running into the risk of being the one of the first ones that go bankrupt in this crisis – we rather want to have them as part of a non-market-driven “last resort” system. And in such a situation, a strict application of IFRS 9 is not really a big help.

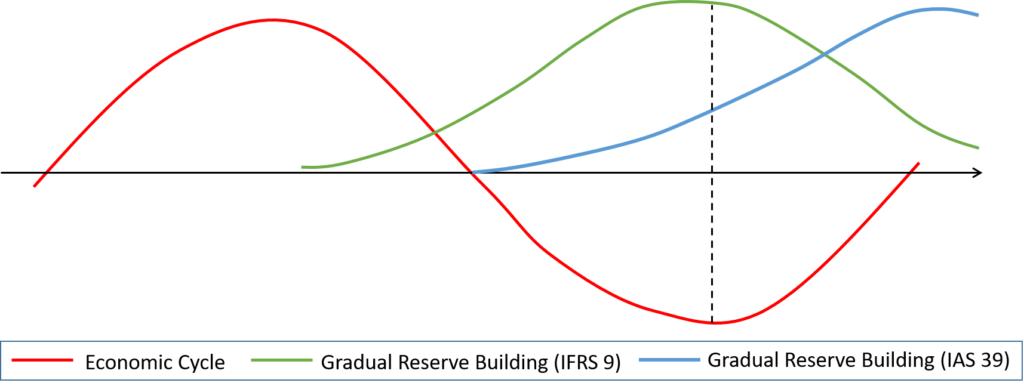

The following graphs highlight this. The first one adresses a “normal” crisis. Due to the longer lead times banks can gradually build up reserves and hence keep their equity safe. Even at the time of highest economic stress (the dotted line in the graph) the IFRS 9 banks are still in good shape because they have fully provisioned for the economic credit risk situation. The IAS 39 banks are lagging in terms of reserve building and run risk of getting into financial trouble themselves.

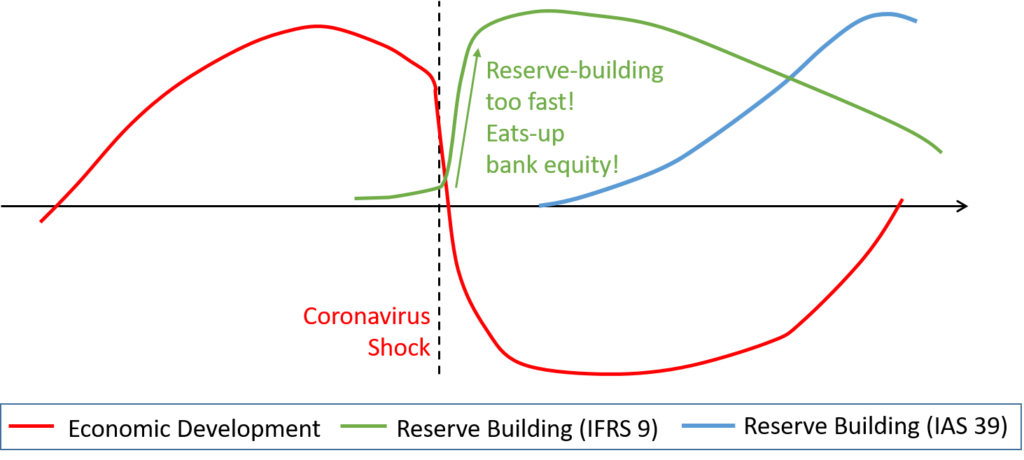

The second graph depicts a coronavirus-type crisis – a sudden, independent shock. In this case, IFRS 9 banks must immediately build-up reserves. They cannot do this gradually and hence they cannot do this by protecting their equity. In contrast, reserve building runs immediately against the equity account and eats it up. In contrast, the IAS 39 banks can wait until they see the first non-performing loans until they have to build up reserves (this might also not take too long after the Coronavirus shock, but at least it will be later in time).

This big problem of IFRS 9 has already been realised in recent days. On Friday, 20 March 2020, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced that It does not want to see banks to set aside too much reserves against loans because that would further reduce the flow of credit to the economy. The ECB suggested banks should apply so-called IFRS 9 transitional rules, which allow some measurement discretion, and it said that its supervisors will „exercise flexibility“ in their bank assessment.

We perfectly understand these statements from a macro-economic point of view. They clearly point into the right direction. However, while the intention is good we think the ECB communication is quite weak. The comments suggest that we now have a new accounting rule which has been designed to better deal with crises, and now that we see the crisis we already relax these rules. These comments definitely do not help to strengthen the trust in the IFRS – quite the contrary.

The ECB should make clear that IFRS 9 is a good (or at least not a weak) set of rules in a market-oriented system. But if we want to take banks out of a pure market setting and use them as part of a solution to the problem (which the ECB comments clearly showed and which we perfectly understand) then we have to apply additional rules which might differ from the market-system-based ones. These additional rules then could be e.g. a temporary relaxation of the IFRS 9 rules. We think it is highly important to clearly make a difference here because otherwise we will have the big discussion about the general usefulness of IFRS 9 once the coronavirus crisis has softened a bit.