The German transportation-focussed engineering company Schaltbau Holding AG went through a deep performance valley during the last years. With ca. 45 mio Euro cumulative operating losses between 2015 and 2018 the future of the company was strongly at risk. In 2018, however, the company seemed to have managed the operating turnaround with double-digit revenue growth rates and an adjusted operating margin of ca. 3% (after ca. 0.5% in 2017). While this margin is still far away from the old levels of 7%-9%, the company is definitely heading into the right direction operationally. For 2019, the big challenge is now the restructuring of the liability side of the balance sheet (amongst others a ca. 100 mio. Euro syndicated credit line has to be refinanced, which compares to a current market cap of 225 mio Euros).

In June 2019, Schaltbau announced that it has basically reached an agreement for a new syndicate loan facility amounting to 103 mio Euros. Additionally, the company plans to set up a receivables securitisation program worth ca. 35 mio Euros. While we do not know any more details about this securitization program we assume that it will attract some investor interest as securitization can be quite an attractive tool for investors in these days where interest rates are close to or even below zero for many investment alternatives. For equity analysts, however, securitisation programs are not always easy to be set into economic context as they combine a lot of financing, investing and operating characteristics which have to be properly separated and accounted for in the valuation models. Below we take the Schaltbau-example for some clarifications on what is necessary to tackle such programs from an analytical point of view.

For our analysis it is simply assumed that the receivables (or parts of them) are transferred to an external party. This may be by a real securitization or by a factoring program or by something similar. The concrete nature of the program is currently not known to us but this is not of big relevance for our explanations. It is also important to note that we do not at all want to blame Schaltbau for something bad (or praise it for something good), we simply want to use this current example for highlighting some potential analytical pitfalls.

For such securitization transactions there are basically two possible accounting treatments. The first one is a pure lending with the assets used as collateral. This is often the case if not all risks (in particularly not the risk of uncollectability – a so called recourse factoring) change hands. In this case the accounting treatment is quite straightforward with the receivables staying on the balance sheet and a liability position now standing against it. In this case, there are admittedly no specific challenges for analysts. However, we do not think that this is the way Schaltbau wants to go (but we do not know) or at least we would rather want to assume that this is not the Schaltbau-way in order to shed some light on the real analytical challenges.

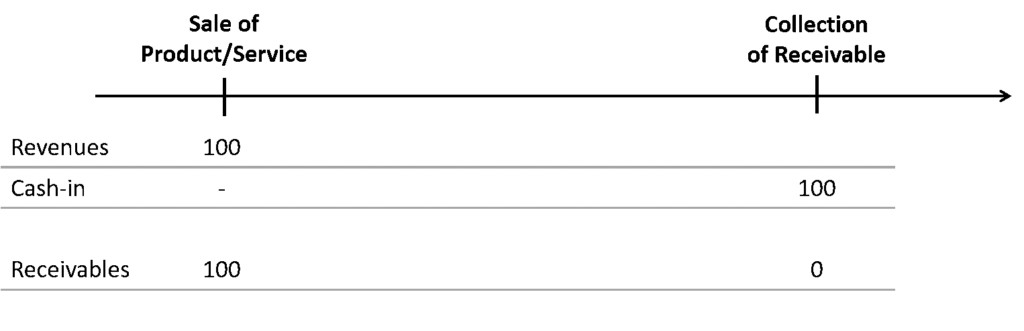

The other transaction structure is a true sale (non-recourse). Here the receivables exit the balance sheet and the company receives a selling price. This is the analytically interesting version of securitization. But let’s look at this step by step. Starting point is a normal business situation in which a company sells a product or a service and grants the customer a certain time to pay the bill. This is a pretty much straightforward transaction. At time of sale the company builds-up a receivable and takes it out of books again once the customer has paid.

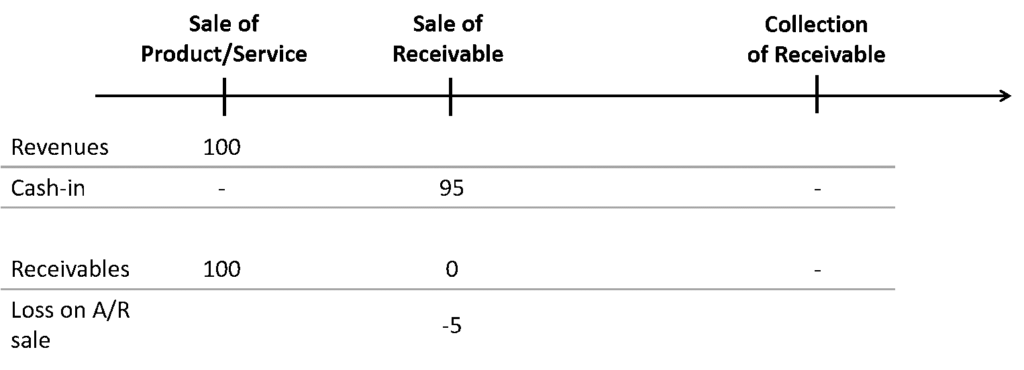

Now we assume that the company decides to sell the receivable before its collection to a third party in order to early-realise a cash inflow (here: only one single transaction!). Of course, the company has to suffer from some discounts on the sale (due to uncertainty and/or time value of money effects). Typically, the situation now looks as follows.

In the corporate accounts this cash inflow from the sale is usually classified as a normal operating cash flow. But from an economic point of view it is questionable if this is really an operating cash flow. It could also be a financing transaction (which is in line with the purpose of such transactions) or a de-investing transaction (which is in line with the non-inventory selling character of the transaction).

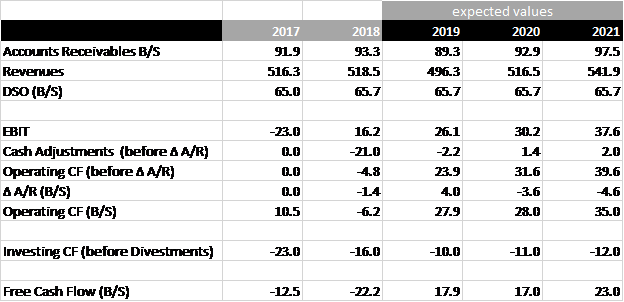

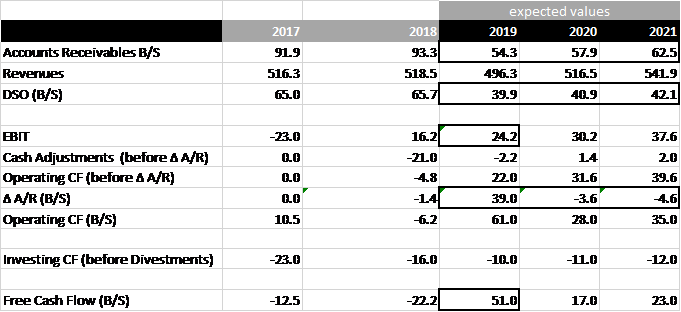

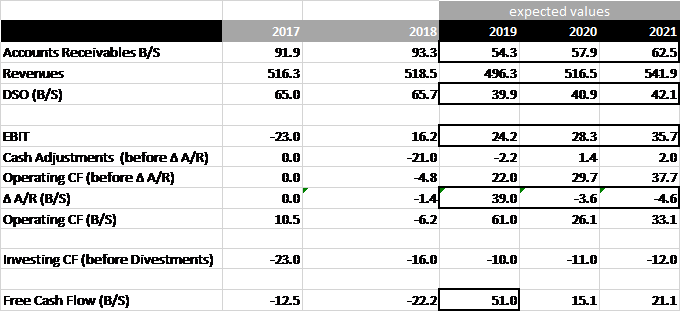

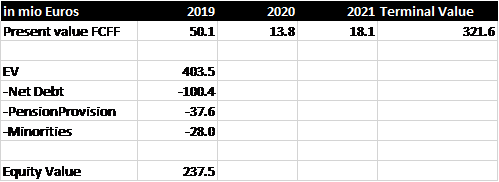

However, from a valuation point of view it does not matter how you qualify this transaction (operating, financing or investing), it is only important that you treat it consistently in your model. Below we now apply a typical recurring securitisation transaction to the accounting of Schaltbau to highlight the valuation effects. It is assumed that the company goes for a 35 mio Euro receivables securitization program (as indicated) at the end of 2019 and that it keeps this level over time – i.e. that it resells fresh receivables once the old ones have been collected (take care: here a repeated transaction is necessary!). This is a typical structure of a securitization program. Starting point of our analysis is a simple valuation of Schaltbau BEFORE the securitization program, using I/B/E/S forecasts for the coming three years and some further own assumptions (e.g. on the translation effects from EBIT to operating cash flow and on sustainable capex). We have further already used normalised numbers as a 2018 starting point (i.e. stripping out any effects from the recent disposal program). The model is of course NOT meant to provide any investment recommendation, it is simply structured for didactical reasons here. The valuation model for Schaltbau in September 2019 here looks as follows:

Here A/R stands for accounts receivables, B/S stands for balance sheet, i.e. accounting measures. Further, DSO are the “days sales outstanding”, a measure for receivables management efficiency. It is calculated by (AR/ Revenues) * 365. Further using a WACC of 7.2% and a long-term growth rate of 2% (our assumptions here, for the message of this analysis the concrete numbers are not relevant), we get the following enterprise value (EV), respectively equity value:

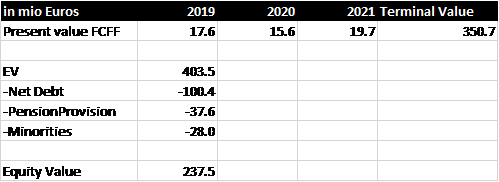

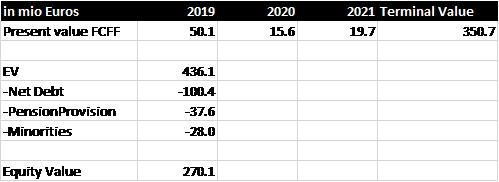

Now we assume that Schaltbau goes for the securitization program (all other things being equal, i.e. we do not take into account any further debt restructuring measures, we also assume that there are no tax effects from this program). Here it is assumed that the company has to take a discount to the transaction which is equivalent to its time horizon-specific financing costs. In our model this is roughly 5-6% p.a. (although in reality it will be lower as we mix here detail planning phase and terminal value effects for reasons of simplicity). If we now – as it quite often done in practice – apply this discount only once at program initiation to our numbers we get the following results:

The framed cells show the changes in our model. Mainly a) the change in the amount of receivables and b) the one-time hit to profitability (here as a reduction of EBIT). Applying now our valuation parameters to this new setting leads to:

This is a much higher enterprise and equity value! And this is something we see quite often in analyst research… and it is wrong! The problem is here that the discount to profitability is only applied once but in fact the company has to suffer from this discount each and every time when it sells new receivables, there is no mercy! If a company starts with a securitization program and wants to keep it alive then they have to give away something on a recurrent basis in order to benefit from this early cash-in of receivables. And hence: If we apply the discount on an annualised basis in each year, things look quite differently:

The valuation model now looks as follows:

We can see that there is an intertemporal shift (more concretely: a front-loading) of cash flows but that the present value of these cash flows is exactly the same as in the case without any securitization program at all. In fact, if properly modelled the securitization program is value neutral if the company has to take a fair discount to all the revolving transactions amounting to the cost of financing!

Now one might say that the securitization program is not an operating but an investing transaction. But then the effects will simply show up in the investing cash flow section – no change to the free cash flows as mapped above. And if you want to qualify it as a financing transaction then there are no effects in the free cash flows AT ALL as compared to the no-securitization situation – but also the WACC does not change as we do not assume any tax effects (the increase in the cost of equity due to higher leverage is perfectly compensated by the now higher debt/equity ratio, this is the Modigliani/Miller finding). Result: However you want to look at it: No change to our original “no-securitization” situation in value terms – whatever you want to qualify this transaction.

This no-change-in-value is an important finding from a valuation-technical point of view but it is not the end of the story. Two more aspects are worth considering. First, there might be a positive effect for enterprise value and equity value for companies like Schaltbau (which are in a quite tough financial situation before the securitization program) from the decreasing bankruptcy risk. And it is true, we can in fact observe such an effect in practice. And second, there is the big question whether Schaltbau will be able to go for this program by only paying the normal financing costs. In many cases we see that already distressed companies have to give more than just the financing costs to enter such transactions – which is then a negative effect. What is the combined consequence from these two aspects? We do not know yet, we have to balance them once it becomes clear what the terms and conditions of the program are. It could turn out to be slightly net-value-positive (if the program is well structured) or it could be net-value-negative if it is not well structured. Our example case just looked at the pure technical aspects here, neglecting these two aspects.

The key Take-aways from our Analysis

- Take care with securitization programs from an analytical point of view. Usually the operating cash flows look very good initially. And there are a lot of analysts who fall for this initial positive bias. But securitization is a transaction that companies never get for free. In the best case it is value neutral. But analysts can only find out if they properly model the whole transaction cycle – which means for the case of a sustainable 35 mio Euro level in the case of Schaltbau that they have to take any discounts into account until eternity (simply because the company has to continue with this program until eternity on a revolving basis if it wants to keep this level).

- Technically, the securitization program does not have any value effect if the company can do it exactly at its cost of debt financing (bankruptcy risk-decreasing effects set aside). But whether this is really the case is something which is up to a separate analysis. In a real world setting (i.e. including bankruptcy risk effects) analysts have to compare any positive effects from an improved credit profile to any negative effects of an expensive transaction structure (and there is often a quite expensive structure in reality!). Outcome: Unclear before we know the details!

- We write this article because we can see it quite often that analysts and investors do not take into account the whole-cycle nature of such securitization programs – i.e. that in fact the early year cash-positive effects come at the cost of negative outer-years cash effects. And there are some CFOs who know this! That is why companies do not only try to benefit from a one-period effect but rather to make this effect somehow sustainable by simply increasing the securitization program over time. This goes back to the old ugly-CFO rule: ‘If you want to make use of a one-time effect for a longer time, then build it up over time’. In the current context this means: Companies start with some securitization and increase the amount of the program over time. Often this is combined with comments like: ‘Due to the success of our initial selling… we continued…’ or ‘market testing showed us that the appetite for this product is much more attractive to investors…’ or similar. Effect: If analysts do not take care and do not constantly adjust the outer years effects, then they falsely overweight the positive initial operating cash flow effects (which is only in 2019 in our example above) also in the following years. And if analysts see these effects for three or more years they might be tempted to take it as a sustainable effect. This is a very dangerous situation as in reality there is no eternal possibility for increasing such a program. There will be definitely one day when the music stops! We do not know whether Schaltbau goes this way but it is important for analysts to keep this in mind when analysing securitization programs: An initiation of such a program is as dangerous from an analytical point of view as is the constant increase of such a program!

- Sometimes such securitization programs come along with an increase in the aggressiveness of revenue recognition. This is just a general observation – no relation to the Schaltbau case here. This more aggressive revenue recognition is often possible because DSO decrease in the context of the securitization transaction and so companies can easily mix this up by some real-world revenue recognition effects (e.g. being a bit more relaxed in their collecting terms) which are usually now more difficult to spot for analysts because there is not a smooth historical time series of DSO measures anymore available. Take care of this!

- Here we didn’t take any tax effects into account in order to get a simple structure for didactical reasons. This might be different in reality.

- What we wrote above about DCF models is equally true for multiples. Here you also have to take care that you take this multi-year effect into account. This is particularly true if companies manage to take this transaction discount somehow OUT OF operating earnings (we have also seen these cases in practice). Be particularly aware of any operating cash flow multiples as we now know that operating cash flow effects are not at all sustainable in case of securitization programs.

Finally, a concluding comment on Schaltbau Holding AG: While we looked critically at the situation of the company in the past in a corporate governance setting (see https://www.finance-magazin.de/blogs/was-wirklich-zaehlt/schaltbau-ag-welchen-preis-hat-der-widerstand-gegen-aoc-1404161/, only available in German) we just used the company here for an example on how to include securitization or factoring or similar programs into our research from an analytical way. We do not know how the program will be structured and we give Schaltbau all the credit of doing this transaction package properly. This is finally not at all an investment recommendation in any direction.