(English version of the VALUESQUE German blog post, 4 February 2019)

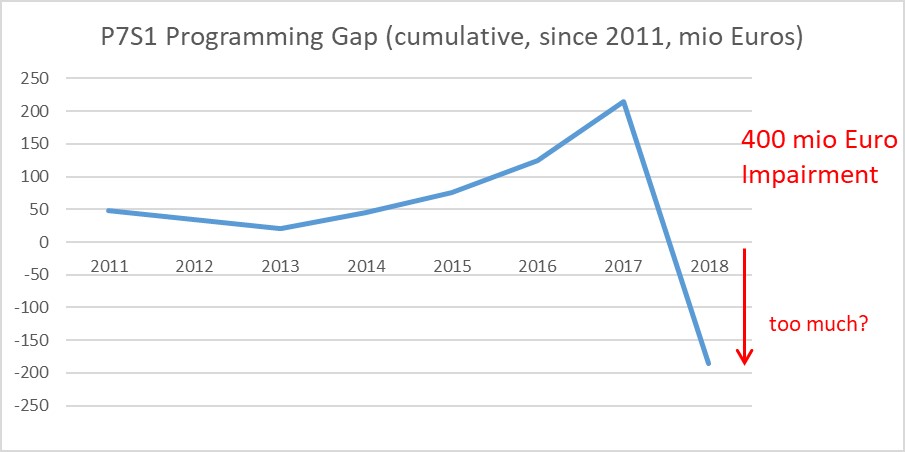

Impairments and what investors can read from them is an evergreen in financial statement analysis. Today we have a look at a very specific one – in fact an event with a really super-long running-in phase: The so called “Programming Gap” of ProSiebenSat1 Media SE – related to quite a material asset of this company – has earned some sort of a cult status at capital markets over the years. The programming gap is the name for the multi-year negative difference between accounting write-downs and cash investments on programme licences of the Munich-based television and media company. This excess investment status would not be a problem if the revenues related to programme licences would develop in a very positive way (then it would be a driver for growth of the programming base), but sales didn’t develop this way! As a consequence, over the years many investors got more and more the impression that the programming gap was rather the result of scheduled accounting amortisations being too low (probably because of a too long accounting useful life), with the nice effect for ProSiebenSat1 that earnings looked much nicer than they were in fact (lower amortisation = higher earnings).

However, according to the old capital market bonmot “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop”: such a gap cannot be built-up endlessly, even if ProSiebenSat1 managed to do so very well over the years. And so investors’ clamours of indignation with ProSiebenSat1’s accounting proceeding with the programming licences steadily increased over the past years. But in November 2018 it seemed as if their voices were eventually heard. ProSiebenSat1’s CEO Max Conze who was just appointed to his present position in June 2018 (see below why this circumstance is relevant here) announced at the company’s Capital Market Day that this accounting hot potato would now be addressed by applying a ca. 400 mio Euro impairment to it. And whilst some investors and analysts showed a sigh of relief and already wanted to put a tick behind this long due correction issue, Max Conze added this fatal sentence: “There will be no unpleasant surprises anymore”. Most market participants were happy (“great if nothing like this won’t happen again”), but a few investors scratched their heads about this additional comment: How should Max Conze know that? If he now impairs the licensing assets down to the fair value – what he should do according to the accounting standards – but in future the business prospects for the licencing business further deteriorate… well, then he would have to write-down again. Not particularly good for future earnings but c’est la vie. That’s exactly the idea of Impairments! So why the optimism there won’t be any unpleasant surprises anymore?

Based on numbers as of 2011, Programming Gap was already existent before. Hence, the developments are partially estimated here.

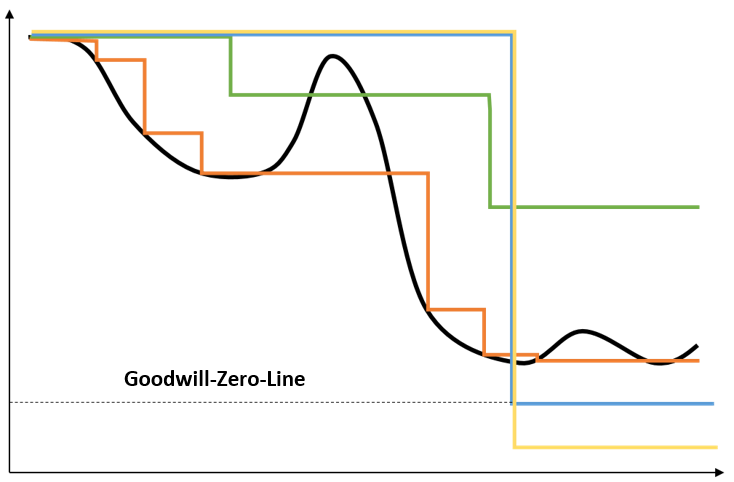

To set investors’ frowns with Conze’s comment into economic context we have to dig a bit deeper into the accounting topic “Impairments”. In fact, impairment are not impairments are not impairments. This is the case as impairments regularly require a lot of assumptions on future cash flow generation and cost of capital, and therefore management has a not inconsiderable margin of discretion here. The following graph highlights a few typical real-world Impairment cases. As a benchmark the actual fair value development of the assets under analysis is indicated by the black thick line. It is here assumed that management can in fact estimate the fair value of assets with a reasonable degree of certainty (which is admittedly quite a strong assumption but appropriate here for illustration purposes).

Case 1 Orange – Proper application: This is the ideal economic case, in line with the intensions of standard setters according to IFRS and US-GAAP. (Carrying) book value is quarterly adjusted downward if market values are lower (with a few insignificant technical restrictions). However, upward value adjustments (at least with regard to goodwill) are not allowed. Important to note again: Here impairments are the result of actual fair value developments. Consequence: With a clean conscience management can’t promise anything (!) to capital market at any point in time. When fair value drops further in the next quarter then further impairments are necessary again. That’s how accounting goes in the case of proper application.

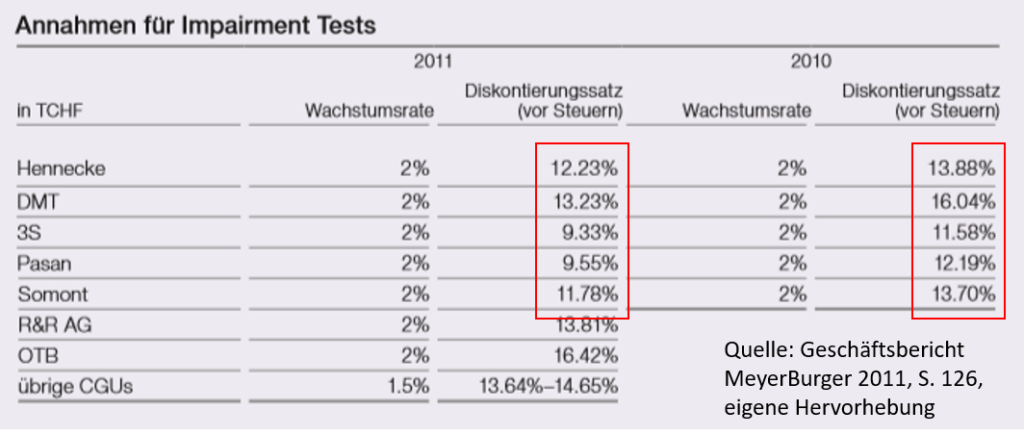

Case 2 Green – The “shrew” application: That’s the typical real-world way of application. Impairments are happening but… too little, too late (see also for a nice academic study Hirschey/Richardson, FAJ 2003)! Management makes use of its margin of discretions and shys away from impairments until a critical threshold is crossed, from where auditors could no longer look away. Because this case is so common in reality we do not provide a list of examples here. But if you ask yourself now how CFOs can apply this strategy in practice (without of course giving an advice here): The best way for disguise (i.e. the weakest point of auditors’ detection) is usually here the detailed planning phase (i.e. the first couple of years of cash flow planning) – according to my subjective experience. That is the phase where it is easily possible to portray the future a bit more positive than it really is – extremely difficult for auditors and outside investors to comprehend. Less in focus during the last years are, in contrast, cost of capital and long-term growth rates. Simple reason: Auditors have way more benchmarks here and can much easier spot aggressive assumptions. But to be honest, this doesn’t mean that cost of capital and growth rates are fully out of the focus of CFOs. In 2011 for example, diamond wire saw producer Meyer Burger Technology AG managed in the middle of the big solar crisis (these saws are mainly used in silicon treatment) and hence in a significantly riskier business environment (stock price Meyer Burger end of 2010: 23 Euros, end of 2011: 12 Euros) fully counterintuitively to reduce its cost of capital for its impairment tests.

Case 3 blue – soft kitchen sinking (also known as “relaxed life”- kitchen sinking). From here, it gets interesting (and also a bit messy). Kitchen sinking describes a technique – also known as “Big Bath” accounting – where mainly everything (or at least a lot) that is possible, is poured down the kitchen sink. Much more than is necessary from an economic point of view! But why should management, who is usually rather interested in a good corporate performance proceed this way? The answer is quite simple: If things are already going bad, then all the bad things (or a major part of them) should be recognised now and in this period. This makes a free pathway for later periods because then the probability of further future adjustments is quite low. Or put it differently: it is highly improbable that there are more impairments to come in the coming years. Additionally, when major impairments take place, stock markets probably get a bit insensible for the concrete amount. They simply don’t care a lot whether e.g. General Electric writes-down 23 bn USD or only e.g. 18 bn USD (see https://valuesque.com/2019/03/21/ges-23-bn-usd-goodwill-impairment-the-non-soft-hard-cash-financial-analysis-problem/ on why we have chosen this example here). Investors simply often classify such proceeding in a generalized “very bad”-category. Usually, soft kitchen sinking is restricted to (non-amortisable) intangible-only write-downs, not more. In soft kitchen sinking a CFO just doesn’t want to be burdened again in the future with this “daft” Impairment issue – he rather wants to spend a “relaxed life” in the future. Indications for analysts for a soft kitchen sinking are management-comments like: “…no more unpleasant surprises in the future,” (Sic!), “…corrections of past problems”, “…a clear and fresh basis built”, etc. Hence, what might seem to be a sedation of the current situation for some investors should make an expert rather listen attentively.

Case 4 yellow – Hard kitchen sinking: If CFOs dump more into the kitchen sink than just goodwill or other non-amortisable intangibles (such as brands in some cases) then they are usually up to really bad things. If they additionally (or exclusively) write-down depreciable physical fixed assets, intangibles that are subject to scheduled amortisation or inventories they want to set a totally new basis for future performance – not only having a relaxed life but rather a blue-sky experience in the future. Value adjustments of machines now lead to lower scheduled depreciation/amortisation in the coming periods (the depreciable amount is now lower). Similar for intangibles that are amortisable on a scheduled basis. And lower inventory values flow into the future profit & loss statement at lower costs of goods sold. Result: future accounting expenses are lower and thus future earnings look better than they would without this hard kitchen sinking. Moreover, the Impairment is often already forgotten by market participants the next year. A wonderful future earnings enhancement effect! Conciliation comments from company representatives – such as in the case of soft kitchen sinking – are by the way heard rather seldom here. The perspective of a nice future performance is often enough for management, victory chanting would be rather too suspicious. If you want to see a nice example for a hard kitchen sinking where really everything can be observed, you should have a look at the (in-) famous 2014 annual results of Tesco PIc.

Three sub-variations of hard kitchen sinking are worth having a closer look at:

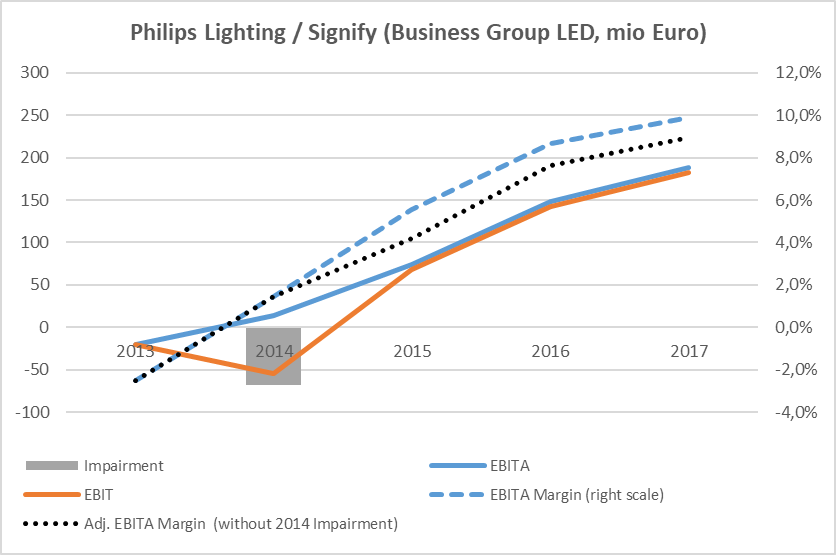

First, the impairment of non-goodwill-assets in a sub-segment of the company which is not in the focus of capital markets. These impairments are often overseen by the stock market but still have exactly the desired effects for companies, also on a consolidated basis. In 2014 for example, Philips Lighting NV (today Signify NV) which saw itself already in the beginning of an upswing phase, additionally helped itself by writing down non-goodwill-industrial-assets in the amount of 68 mio Euros in its LED-division (why, if the upswing was already there?). As a result, the cumulative depreciable asset base has shrunk with the result of a quite remarkable boost to earnings in the future. The following graph shows that the actual EBITA margin of the LED segment in the coming years is clearly higher after the impairment than it would have been without the impairment.

Second, it is not only about assets. It is also possible to go the liabilities way, e.g. to upward adjust some provisions. Outdoor advertiser JCDeacaux SA build up provisions for “onerous contracts” in 2015 in the course of its CEMUSA-acquisition, only to release them step by step in the coming years (sometimes amounting to more than 15% of operating earnings).Effect: major boost to its earnings in the years 2016 and later.

And quite related to this latter point: Third, such adjustments are very popular especially in connection with M&A transactions. Why? Value adjustment for financial assets or provisions within a transaction usually don’t stand out. Ok, perhaps goodwill is a bit higher as consequence of this proceeding than it would be otherwise but that’s usually just accepted by capital market. And Goodwill is not subject to a scheduled amortisation. Its accounting development can – see case 2 green above – be actively managed by CFOs at least to a certain degree. A perfect boost to future accounting performance! For a really infamous example have a look at the proceeding of Carrillion Plc. in earlier years – a company which is now insolvent and which has been raised a lot of publicity for its – gently speaking – creative accounting activities quite often in the past. Concretely, in the course of Carrillion’s Alfred McAlpine takeover (2008) and the Eaga acquisition (2011) the British construction company performed value-downward-adjustments already during the purchase price allocation phase (PPA) of working capital positions, IT-assets and similar amounting to more than 20% of the purchase price in each case – this made their accounting life much easier in the following years (although not on a sustainable basis as we know today).

Whoever now wonders whether management perhaps might lose a lot of reputation as a consequence of such too-high impairments, a loss that probably cannot be compensated later through higher earnings or a “relaxed life”, gets two counter-arguments:

First, already addressed above, a lot of negative information usually disappears at large and is hidden in the big one-time impairment pot so that its full severity gets often not noticed by capital market participants. Experience shows that in sum and over the years the “positive” effects from a good ongoing performance weighs much stronger than the one-time negative effect. Obviously many investors have a blind eye here. And this is a big inefficiency of capital markets (and of many sells-side analyses).

Second, much of our accounting is management business not investor business. Kitchen sinking can be observed very often – though not only – following a management change. And management changes usually provide a high individual benefit impact for the new management by blaming the whole drama (i.e. the reasons for the impairments) on the old management. Fresh management’s slogans are often: “We came in here and didn’t expect anything bad – and then we saw what really goes wrong in this company. We had to quickly repair it. But now – with us – everything will be fine!”. As a consequence, reputation of new management often rises even more in the eyes of capital markets by kitchen sinking, since this new management finally seems to clean up with inherited liabilities and leads the company into a new, positive phase. Another strange market inefficiency…

Regarding ProSiebenSat1’s programming-impairment, everybody can now form his own opinion here based on the explanations in this post. Important: Don’t forget that in all described examples of potential kitchen sinking cases there might also be good and justifiable reasons for the write-downs. We only provided some indications here. In fact, finding out about the true nature of an impairments requires a case-by-case analysis. And as always: This post doesn’t imply any investment-recommendations.