M&A accounting is certainly one of the trickiest playing fields in accounting for a couple of reasons: 1) It is aperiodic and therefore breaks into our normal and familiar accounting often like a foreign substance. 2) It is about values (i.e. present value of multi-year future cash flows) and not about normal period-specific revenues or expenses. Therefore it usually covers more than just the usual one-period-effects. 3) These multi-year economic effects are followed or accompanied by normal one-period effects, i.e. after the acquisition is done or even during the integration process. Therefore it is important from a financial analysis point of view to properly separate the multi-period effects from the one-period ones. 4) The reported numbers in M&A accounting cover a lot of procedures that are not retraceable by investors in detail, e.g. the single assumptions behind the whole purchase price allocation are mainly hidden for outside investors. 5) The last two points (3 and 4) together set a very dangerous dose of incentives for companies to palm away some future periodic negatives by including them into the one-time M&A effects.

There are a couple of techniques on how to hide away future expenses. We are going to discuss some of them in this and in future blog articles. Starting point today is the case of the so called earn-out clauses which grant the seller in a transaction a later purchase price adjustment if certain benchmarks of corporate performance are met in the future.

An earn-out is a quite reasonable purchase price adjustment clause in M&A transactions as it helps to overcome typical information asymmetries between the seller (knows the company very well) and the buyer (usually has an information disadvantage despite thorough due diligence). The earn-out works as follows:

A certain part of the purchase price is withhold by the buyer and subject to the actual future performance of the company. So if the (well-informed) seller promises a blue-sky future of the target company and it does not happen he or she gets a lower total consideration. If however, his projection is right (or even better than expected) then he or she gets a higher total consideration. This clearly limits the risks of a (not so well-informed) buyer and also motivates the seller to be honest in the whole transaction process.

As long as we do not know whether the performance targets of the earn-out-clause are met, the potential future purchase price adjustment hast to be treated as a liability for the buyer – valued at the expected present amount of future price adjustments. While the concrete valuation is also a tricky task it still follows normal rules of pricing future expected outflows. So far so good from a financial accounting point of view.

But what if the seller is not really an ultimate seller but rather part of the future combined company? We see this quite often when companies are buying start-ups with a founding-management with specialist know-how. In these cases, taking over the former management is often mandatory for supporting the future success of the transaction. But we also see it in bigger transactions where the (at least partial-) owner-management of the target company finds – for good reasons, e.g. because of the recent track record – a new management place in the now combined company. In all these cases it is no longer that clear what the ‘earn out’ is really about because the seller still impacts the fate of the new company. But then: what is the nature of this earn-out clause in such cases from an economic point of view?

There are two possibilities: 1) it is really an earn-out, just reducing the effects of the forecasting uncertainty of the buyer (unfortunately rather rarely the case if the target owner-management stays in an operating role). 2) it is some sort of an incentive for the newly integrated, former target company owner-management or – even more often the case – it is an outright part of the salary of the former target company owner-management. This second possibility is what we rather see as a typical case in target-owner-management-stay-in transactions.

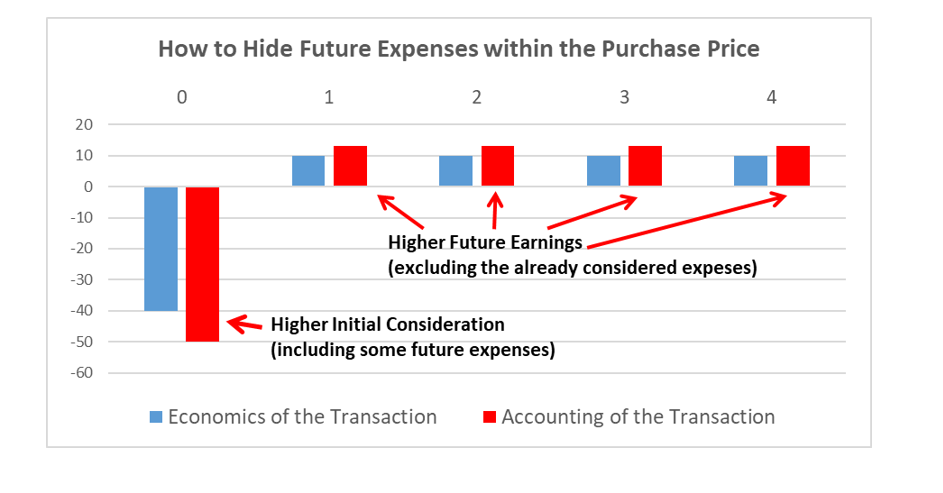

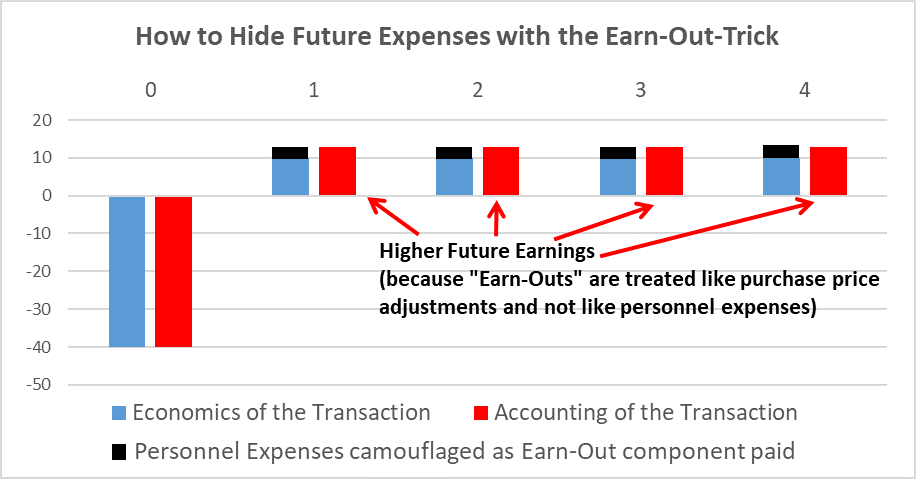

But why is this all important for financial analysis and business valuation? Here is the clue: If in economic terms buyer-companies want to incentivize the target-management for performing in their operating role or if they simply want to pay them for working then it is no longer an earn-out in the strict sense. It is rather an ongoing salary component in the periodic business of the newly combined company. And – again from an economic point of view – it should show up as personnel expenses in the years after the acquisition closing – therefore reducing the future earnings of the company.

But with the earn-out clause communicated to investors it all seems as if the company has quite high earnings in the future (because they are now not impacted negatively by these personnel expenses) but has to suffer a bit from purchase price adjustments for a couple of periods – in the eyes of the investors: because the new company is so successful. What a different picture this is now, isn’t it? And this means for our real world: if companies can paint such a colourful picture for investors by making future expenses rather being part of the original transaction …. they will do it!

The list of real world examples of this trick is very long. Below, for reasons of illustration I provide a couple of recent ones which I became aware of – which is certainly only a tiny part of the total.

In 2017, Tabula Rasa Healthcare Inc. took over the medication management company SinfoníaRx Inc. for 35 mio USD in cash plus potential up to 85 mio USD of earn-outs. The founder and long-term CEO of 2006-established SinfoníaRx now serves as part of the management team of Tabula Rasa which makes the major part of the so called earn-out a normal remuneration component as part of the former CEO’s salary.

Also, in 2017, German life science specialist Sygnis AG (today: Expedeon AG) acquired the UK-based provider of bioconjugation products and services Innova Bioscience Ltd. for 10.8 mio Euros plus an expected earn-out of roughly 2.2 mio Euros (according to the Sygnis 2017 balance sheet). One of the founders of Innova became chief technical officer in Expedeon – and presumably will receive a non-negligible part of the variable ‘purchase price adjustments’ for his performance as an employee in the years after the acquisition – i.e. from an economic point of view as part of his salary.

In 2016, the B2B media company Ascential Plc. bought the US-based data analytics company One Click Retail LLC for an initial cash consideration of 44 mio USD plus up to 181 mio USD (!) of ‘earn out payments’. Ascential informed the capital market that “a portion of the earn-out payments is also subject to founders remaining in employment with the company” and that the payment of earn-outs depends on some performance targets.

It was also in 2016 when Italian media company Digitouch SpA acquired the SEO-specialised web agency Optimized Group for 1.35 mio Euros plus up to 430 thousand Euros earn-out in case the company reaches some performance targets. One of the co-founders of Optimized stayed with the company to become the new managing director of the now-subsidiary and also took the role of Head of International Development of Digitouch.

Only a couple of months ago, at the end of 2018, Mayville Engineering Company Inc. finished the acquisition of Defiance Metal Products (DMP), a manufacturer of component parts for heavy and medium-duty commercial vehicles for a cash payment of 114.7 mio USD plus an additional earn-out payment of up to 10 mio USD which will be paid if DMP meets certain performance metrics in 2019. Although we do not know for sure yet in this case, we think it is highly probable that the former DMP CEO, who is now Chief Operating Officer of Mayville, also benefits from this ‘earn-out’ as a compensation for his services as an employee of the newly combined company. We come to this conclusion as he was also part of the management team of the selling-vehicle that was build-up by the DMP former majority owner Taglich Private Equity.

Lots of examples! And the list is far from exhaustive. In this context I often get the comment from e.g. auditors that this earn-out trick is not a real problem as nothing gets lost here. They argue: Perhaps there is a slight economic misclassification but if we add it up there are still all expenses or cash-outs in the numbers. But as I already wrote above: this point of view is certainly not the right one for somebody who wants to make investment decisions. The problem here is that our accounting system is not only about historic numbers but – even more important – it should bring the addressee into a situation of being able to value the company (decision usefulness). This means for equity valuation reasons: It should allow or at least set the basis for a proper forecast of future earnings or cash flows. And this is a big problem if investors fall for this earn-out trick! If investors do not recognise that future cash flows or earnings are somehow affected by certain negatives (here: personnel expenses) but rather think that this negative relates to a past transaction – the acquisition itself – then there is the risk that they overstate the real value of the company because of overstated forecasted future cash flows… and this is exactly what happens quite often in the real world cases.