(Not only) in my opinion, the seminal and still most relevant paper about bitcoin accounting practice was written about three years ago by Deloitte Australia Partner and former IASB member Henri Venter: Digital currency – A case for standard setting activity – A perspective by the Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB). Based on lots of interesting analyses the paper basically comes down to the following statement: IFRS is not ready for properly dealing with cryptocurrencies (and without explicitly mentioning the paper also implicitly says that US-GAAP is not ready, neither)! This paper should have been a wake-up call – and one with a long run-up. We have been knowing for years that the day will come where cryptoassets become a relevant topic from an investment point of view in some companies and where we will face the accounting question the hard way. But since then not so much happened in standard setting…

Now, with Tesla’s 1.5 bn USD investment in bitcoin and its accounting treatment of this investment (intangible asset) there is tremendous outcry in the press and amongst investors. In the comments Tesla seems to be the baddie that wants to cheat the world. But most comments just stay at the surface of the discussion. To my knowledge, only the brilliant Footnotes Analyst (HERE) argues on level and adds some interesting news to the debate.

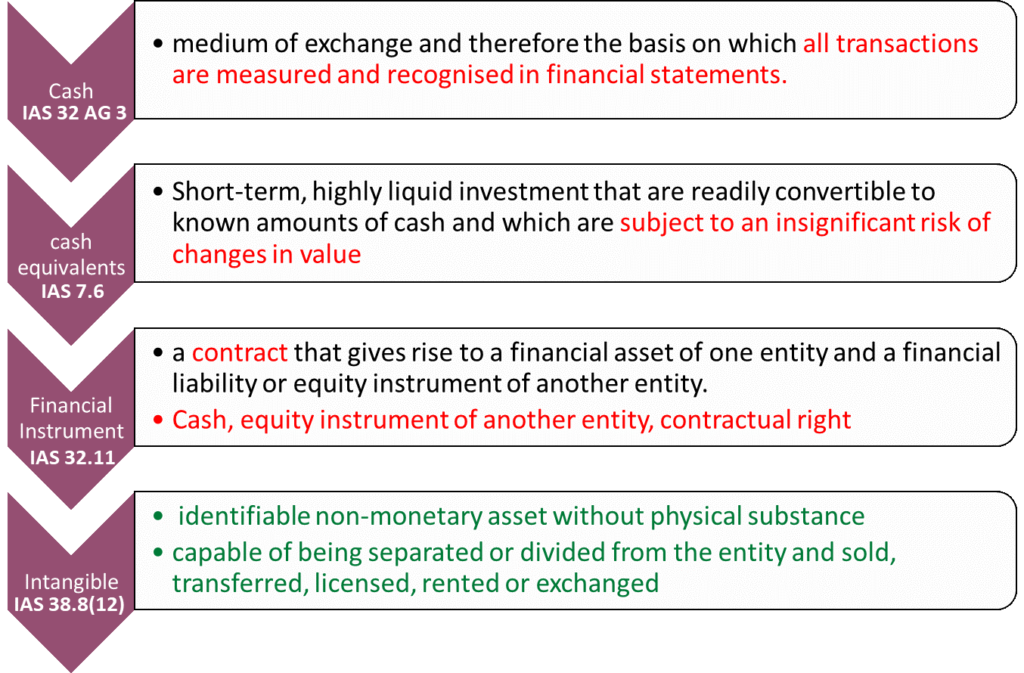

But what is the point with bitcoins in accounting? Why is this such a tricky topic? The short answer is: Because it does not fit into our well-kown accounting system. The longer answer is: Because the usual suspects (Cash, Currency, Financial Instruments) do not apply here, and the technically applicable category (intangibles) is not made for what you want to do with cryptocurrencies. The IFRS classification problem is shown in the following graph (the definitions overlap a bit but this is essentially what the conclusion is about).

Cryptoassets (or cryptocurrencies) are not cash because they are not a medium of exchange for all transactions (though perhaps for a certain subset of transactions). They are not cash equivalents as they are not subject to an insignificant risk of changes in value. They are not financial instruments other than cash or cash equivalents because there is no contractual right behind them. They do, however, fit into the definition of IAS 38 intangibles as described in the graph above.

It is also worth noting that cryptocurrencies can be seen as inventory according to IAS 2 if they are held for sale in the ordinary course of business but this is rather not the case in a Tesla-like case. And some also argue that it could be a commodity under certain circumstances but then still be accounted for like inventory (see the description in the Footnotes Analyst article HERE) The situation according to US-GAAP is by the way quite similar to IFRS.

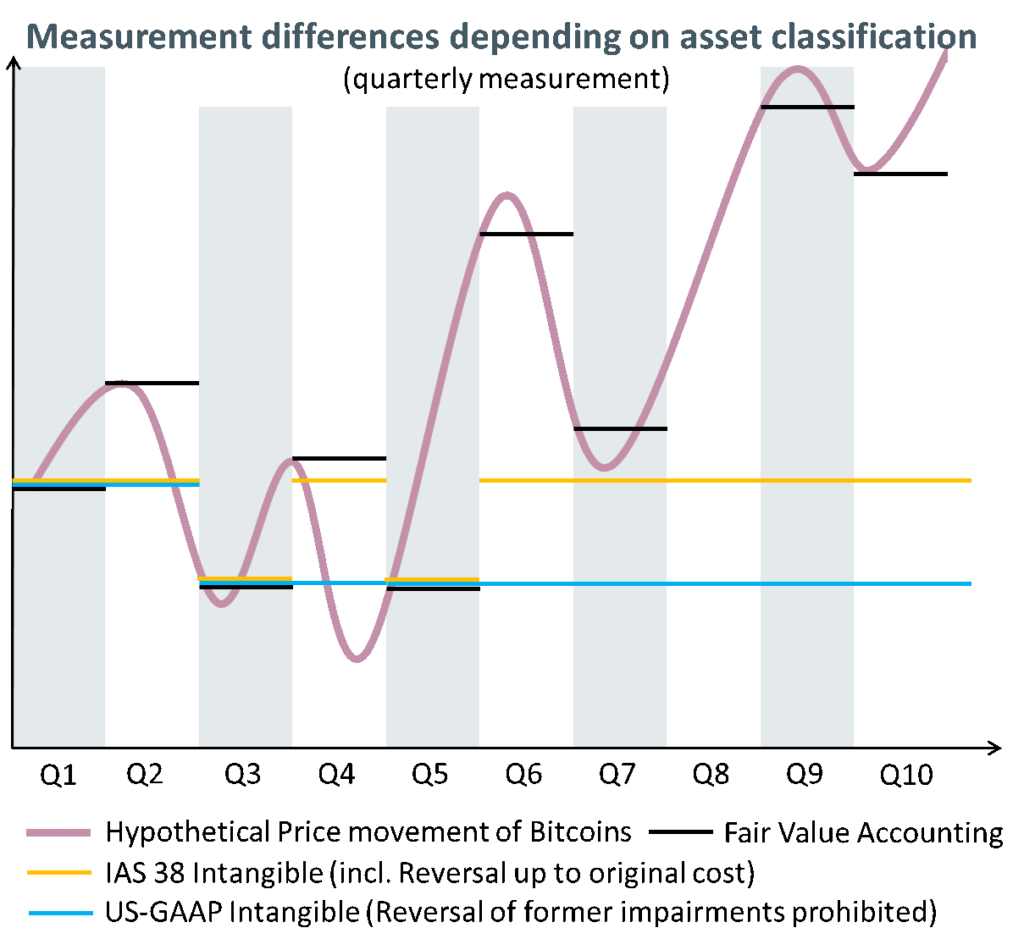

The question of classification of cryptocurrencies is highly relevant because the rules of ongoing valuation (subsequent measurement) differ a lot from asset class to asset class. Without going to deep into things here, the point is that for financial assets companies might get forced to value them at fair value (depending on the concrete sub-classification) while for intangibles companies can opt for fair value measurement but usually they carry them at cost less impairment (the latter is the Tesla way). This means that under an intangible asset classification companies can ignore any upward measurement in their accounts (under US-GAAP companies can even ignore any reversals from former impairments, under IFRS at least these reversals have to be taken into account). For inventory the accounting is similar to intangibles though not the same (here the lower of cost or market principle applies). The graph below highlights the differences in subsequent measurement for an acquisition of Bitcoins performed at the beginning of the first quarter. It becomes clear that the fair value accounting leads to a high volatility (either in the P&L or directly in equity) while cost accounting rather leads to a more stable, but less relevant accounting development.

So far so good. This is the state of things. Hence one important conclusion is that Tesla does its accounting technically correct. Treating Bitcoins as intangibles is the right way to go (for now). But does the treatment as an intangible really meet the economic nature of Bitcoin holdings? This is a question we have to answer in two steps.

First, accounting for intangibles is still a hotchpotch of different perspectives today – in both IFRS and US-GAAP. It is a (some say: bad) compromise of the old literature dispute between e.g. Hendriksen (1982, Accounting Theory, 4th edition) on the one hand side and e.g. Lev/Zarowin (1999, The boundaries of financial reporting and how to extend them, in: Journal of Accounting Research, 37,3, pp. 353-386.) on the other hand side. While the former regards intangibles in their extreme as items without alternative uses, not always separable, only having value in combination with other of the firm’s assets, and with a great degree of uncertainty regarding their recoverability (which ultimately should not lead to recognition of intangibles at all), the latters have made clear that other criteria rather point towards treating intangibles the same way as all other assets regarding recognition and valuation (i.e. with control of the future benefits as a criterion for recognition). This discussion finds its compromise in today’s accounting e.g. in the treatment of R&D expenses – in different ways in IFRS and US-GAAP.

While we certainly do want to admit that Bitcoins is rather something that fits into the Lev/Zarowin definition, we also have to emphasize that intangibles accounting should not be a compromise anymore today nor a like-other-assets approach. There are so many different animals in the intangibles zoo that we cannot lean back to treat this category as one-fits-all. We need differentiation – the same way we differentiated assets in general into different categories already a long time ago. Different nature of intangible means different treatment. And this is what is lacking today in intangibles accounting.

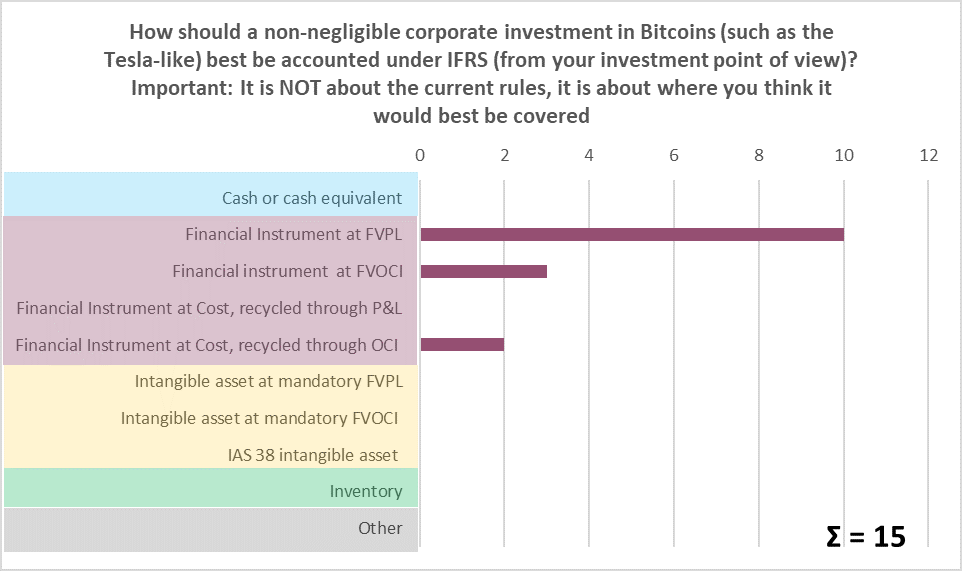

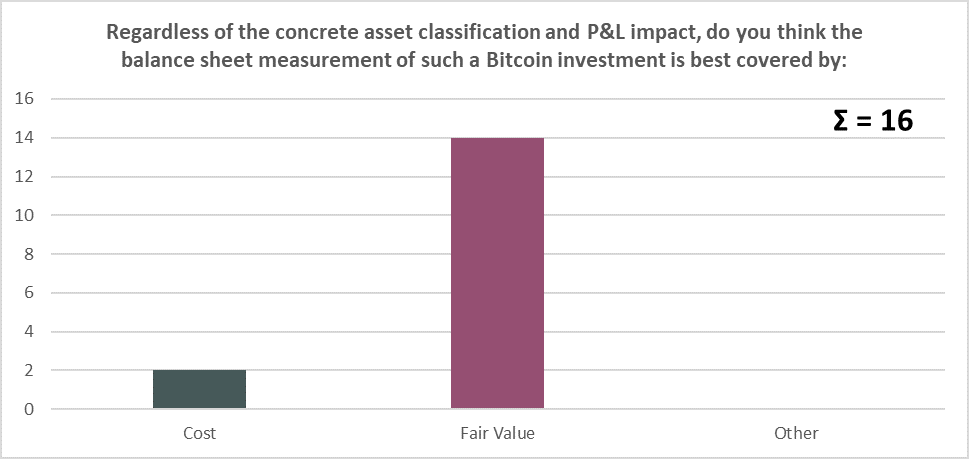

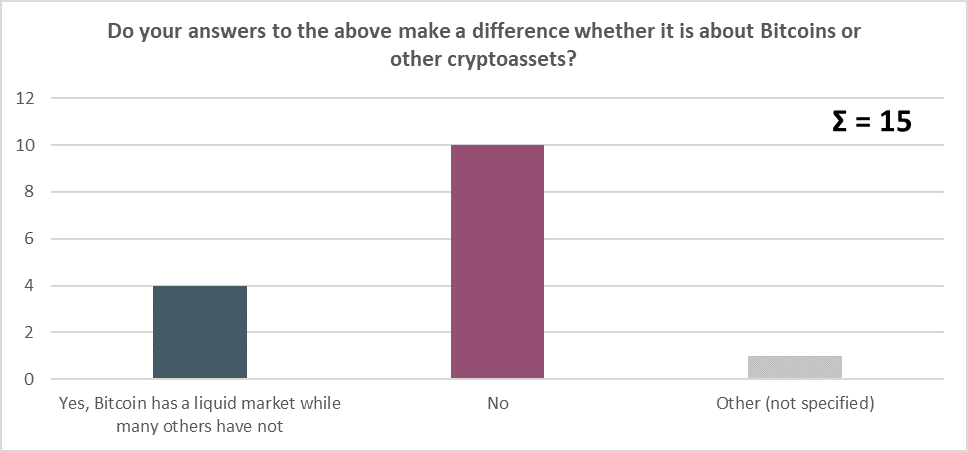

Second, even if intangibles differentiation seems to be a necessary step, this still does not ensure that it would be the best solution to the Tesla-Bitcoin problem. In order to get more clarity, we thought it is a good idea to ask equity analysts and investors about their perspective on this issue. For this we sent out a survey amongst ca. 40 German public equity analysts and portfolio managers. The response rate (16 answers) was ok but not overwhelming. It is clear that this is not a representative survey, but we think it gives some insight into reporting users’ general view on this topic.

We asked three questions. Question 1:

Question 2:

Question 3:

Obviously the message is clear here. Irrespective of the concrete rules every respondent would like to see the Bitcoin investment as some sort of a financial instrument. Most of the respondents want companies to be required to carry such an investment at fair value. And at least a majority does not differentiate between Bitcoins and other cryptoassets here.

To be honest, treating Tesla-like bitcoin investments as financial instruments and measure them at fair value is also my personal preference (but survey participants were not informed about this before). Though if you now think these results might be a good basis for changing IAS 32 Financial Instruments: Presentation you should be aware that we have already been there before. For this we quote from the Henri Venter paper: “We note that the superseded IAS 25 Accounting for Investments was an all-inclusive standard that addressed the accounting for investments. IAS 25 defined an investment as an asset held by an enterprise for the accretion of wealth through distribution (such as interest, royalties, dividends and rentals), for capital appreciation or for other benefits to the investing enterprise such as those obtained through trading relationships. However, IAS 25 was [in 2001, the author] superseded as a result of issuing IAS 39 and IAS 40 [Investment Property, the author] and consequently left a gap that would have addressed the accounting for investments in intangible assets and commodities held for investment purposes.” (See again: HERE) Or putting it differently: the definition of financial instruments has been actively changed away from a situation that allows Tesla-like bitcoin investments to be treated as such – even without knowing at the time of change that we will face a cryptocurrency accounting problem one day in the future. At my experience the probability is now rather low that standard setters will reopen this formerly narrowed definition again – but let’s see what the future will bring.

Perhaps you now say: it is what it is, hopefully we find new rules in the future and until then we have to deal with the current rules. Then we want to remind you here that the history of accounting has always been a rat race between companies and standard setters and whenever standard setters where too late, companies found ways to exploit the missing rules – often to the bad for investors. So, it would be nice if standard setters quickly deal with this issue. For a bit of reading entertainment we list in the appendix some of the more remarkable historical cases where standard setters have been late. The minor ones, the everyday cases, do exist in fact a lot, too.

Disclaimer: We hold no economic stake in Tesla – in whatsoever direction. We base our analysis on imperfect information and hence we might be wrong with some conclusions. This is just our subjective view and no investment recommendation at all!

Appendix: When standard setters came too late…

Let’s start early. Before 1929 companies in the US could play some sort of an event-driven marking-up of certain fixed assets (in particular property). Whenever they required fresh financing they could refer to a liquid market – not often given – or to an ‘independent’ appraiser who revalued the assets. Although from today’s perspective the contribution of this early fair value techniques to the whole-market 1929 crash seems to be overdone as “large revaluations, relative to total assets, were rare.” (Dillon, 1979. Corporate asset revaluations: 1925–1934. in: Accounting Historians Journal 6, p. 12), there were several examples of companies that greatly took benefit from this technique – at least for some time.

In this same pre 1929 era accounting for intangibles was rather free-style – with the auditor’s opinion being the only restriction (but this auditor’s opinion was of totally different quality than today’s one). This also allowed a broad set of internally developed intangibles to be recognised as assets. Although the cost principle was already the dominant perspective at that time, this still allowed to bring advertising costs to build market shares, early project life losses, experimentation costs and similar onto the books (Paton/ Littleton, 1940, An introduction to corporate accounting standards, American Accounting Association Monograph No. 3, p. 31-33, 74, 92,99). While write-ups were rather infrequent, some of these intangibles were assigned an eternal life (i.e. no write-downs) but most of them were regularly amortized. Disclosures about the recognition and valuation were very limited at that time. While research suggests that investors were able to look through most of the management discretion applied in recognising these intangibles (Ely/Waymire, 1999, Intangible Assets and Stock Prices in the Pre-SEC Era, in: Journal of Accounting Research 37, pp, 17-44), i.e. investors stuck to tangible asset information rather, the creativity to push earnings has led into a very low visibility from intangible values – even at the standards of that time. And single companies were perfectly able to lead investors up the garden path with this.

During the 1960 start of the merger wave in the US, investors found that the so called „pooling of interest method“ of accounting for mergers & acquisitions (no uncovering of hidden reserves and goodwill) might allow for hiding prices paid for mergers in the accounting and therefore allow for overstating future performance of the buyer company. Despite intense critique about this accounting-technique it was kept alive by the Accounting Principles Board (APB, the body that replaced the formerly ruling Committee on Accounting Procedures [CAP] of the American Institute of Accountants) which today is often “regarded more as the result of intense lobbying by industry than the product of sound thinking.” (Zeff, 2003, How the U.S. accounting profession got where it is today: Part I. in: Accounting Horizons 17, p. 198). And companies could continue to go for often value destructive M&A activities, something which was only found out years after the deal (when CEOs have already cashed-out). It was only in 2001 when the FASB eliminated the “pooling of interest method” – not a big surprise: against the strong resistance of companies. The IASB eliminated this method only in 2004 when the newly issued IFRS 3 Business Combinations superseded the old IAS 22 Business Combinations.

In the run-up of the US savings and loans crisis (a banking crisis in the late 1980s in the US that led into bankruptcy of roughly 1,000 savings and loans institutions and a wealth damage of roughly 150 bn USD, triggering the big budget crisis and a recession of the US economy) several banking institutions applied the then famous ‘gain trading’ strategy: Banks at that time were not forced to bring financial instruments down to the lower-of-cost-or-market (i.e. could avoid write-downs) while selectively selling well performing instruments to realize the gains in their books. This asymmetric trading strategy led to big overvaluations of the economic books of banks (with mostly the bad investments remaining) – until it all exploded! Not necessary to mention that acting bankers cashed-out a lot before the crisis (the run up of this crisis is also described as the high-time of the so called 3-6-3 bankers: paying 3% on deposits, taking 6% for lendings and teeing off at the golf course by 3 p.m.).