In 2018, Cyan AG, a provider of network-integrated security solutions, acquired 100% of I-New Unified Solutions AG from Austrian gambling company Novomatic AG, in a two-step approach. The acquisition – and particularly the disclosure around the acquisition – had some special features which are worth shedding some more light on here. While we admittedly could not fully retrace all the numbers of this transaction, on a broad basis our picture is the following:

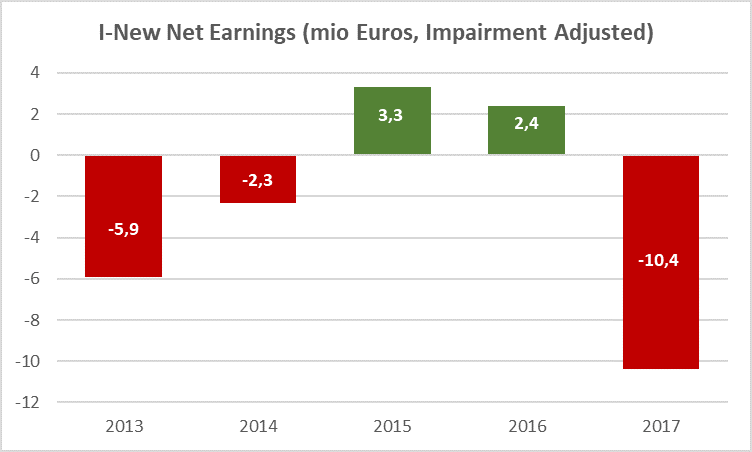

The first step of the transaction (the buyout of roughly 76.8 percent of I-new from Novomatic) took place at a basically zero consideration on an equity level. We can roughly retrace this from the Novomatic accounts and also from the comments of Cyan. Perhaps the real transaction price differs a bit from zero but certainly not too much. And by just looking at the past performance of the I-New stake (since in the hands of the seller Novomatic), a zero equity value at least does not seem to be out of plausibility.

Source: Novomatic Annual Reports

After this initial acquisition of the I-new stake from Novomatic, Deloitte Austria performed a purchase price allocation (PPA). The idea of such PPA is to split the purchase price onto all net-identifiable assets and to assign any remaining non-allocatable consideration to the “goodwill” position. In its purest sense this is usually simply a distribution of an amount of money (the consideration given) to some accounting assets – including goodwill as a residual.

But in the I-New transaction the price was zero. And how should one distribute a purchase price of zero? In such a case a distribution is still possible if the acquirer and the auditors think that the value of the acquired company is NOT equal to the purchase price (zero) but in fact higher. Then they do not distribute the purchase price to the assets, they rather allocate the value (or what they think is the value) to the purchase price. So, quite the other direction. In such a situation the residuum of this exercise is not a goodwill (positive difference between purchase price and net-identifiable-assets) but rather a so-called badwill (negative difference between purchase price and net-identifiable-assets).

Of course, it is possible that the VALUE of some acquired net-assets is higher than the purchase price but for reasons of financial reporting it goes without saying that it needs a lot of confidence in the valuation result in order to come to this conclusion BECAUSE there was still a transaction between two independent parties in place. One obviously needs very good reasons in order to go this way.

As a consequence standard setters have put an additional hurdle to this positive value / price difference. In particularly, they included the so called “attention-paragraph” into IFRS 3. In simple words it says: Dear auditor, please check twice whether the seller is really that stupid (or forced) to sell the net-assets at a too low price (IFRS 3.36). If even after this check the badwill persists, we can isolate basically three reasons for such a situation from an economic point of view:

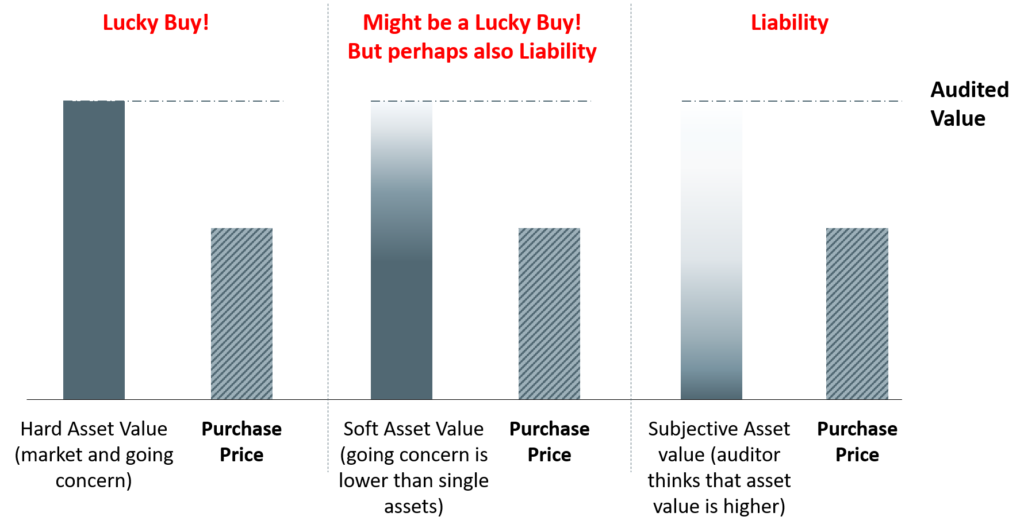

- (1) The deal was simply a “lucky buy”. The buyer was so smart and the seller so stupid (or so forced) that the transaction is just a bargain for the buyer.

- (2) The identifiable net-assets have a higher value than the purchase price because if the buyer would resell them immediately it could reach a higher price than by keeping them in a going-concern world. This might be e.g. in a distress-situation: liquidation seems to be better than going concern. Or a situation where some ramp-up costs (which cannot be recognised as a liability in a PPA) are still to be expected. If the buyer does not want to or cannot sell the single assets immediately (or faces other restrictions) then he paid a quite low price as compared to the single net-asset value. Of course, there might be good reasons for a buyer to go for such a transaction, e.g. if it expects the business environment to improve in the future. Or if it wants to keep the possibility open to sell the assets separately if the business environment does not improve. Typical examples for this could be found in the aftermath of the financial crisis in some financial institution transactions, e.g. when Deutsche Bank bought certain assets from ABN Amro in 2008 and realised a badwill of more than 200 mio Euros on this.

- (3) Auditors or CFOs simply state that there is a higher value in net-assets but unfortunately it is not. Of course, in a proper setting auditors/CFOs would not do this – but you never know. So the assessment of such a situation remains with the investor / analyst.

Now let’s have a look at what this means from an economic point of view. Because the economic (though not the accounting) treatment of a badwill differs quite a lot between the three aspects:

- In case (1) things are quite clear. If indications tell you that it is a lucky buy then the negative difference between purchase price and net-identifiable-assets, i.e. the badwill, is clearly equity. It is without doubts an immediate gain through P&L to the buyer. Great job of the buyer!

- In case (2) there might be some positives to the buyer in the future but this remains to be seen. But still the assets that it bought are quite valuable in separation. In this case, however, auditors really need a clear indication that the fair value of single-assets is indeed higher than what was paid in the transaction. This might be the case if there are highly liquid assets that can be sold without any problems. And if you think that this case (2) applies you also have to ask yourself why the seller company didn’t sell the assets in the first place but rather went into such a disadvantageous transaction. Hence, in economic terms we would feel here more comfortable to NOT treat such a badwill as an immediate gain through P&L to the buyer. In our eyes, this should rather be a liability (standing against the highly valued assets on the asset side) in the first place, and then the buyer can prove over time that this is not correct. If the buyer does not like it: he can sell the net-assets. But we have to admit that it really differs from case to case on how to best treat such a situation from an economic point of view.

- Case (3) is clear again. If by using the leeway of accounting treatment the assets are overstated then the badwill is clearly a liability (in opposition to the overstated assets), or better: the overstatement is simply wrong.

It is, however, this grey area between case (2) and case (3) which gives us a lot of analytical problems. Outside investors do not know whether the assets are in fact overstated without any further information. It is difficult to assess the marketability of the isolated assets. And even case (1) can never be excluded without digging much deeper into things.

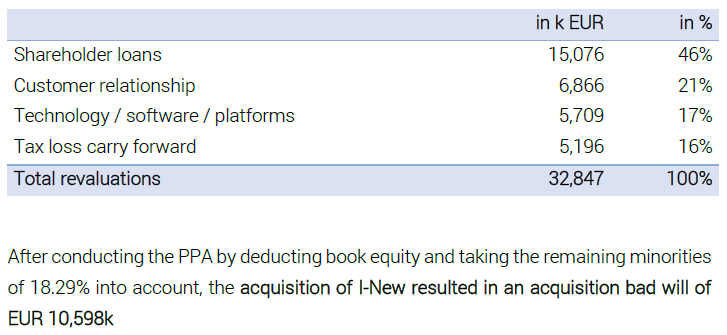

So let’s go back to our Cyan-Novomatic transaction. Obviously, Cyan and Deloitte Austria have revalued some I-New assets (mainly customer relationships and software/technology/platforms), have found a badwill and treated the difference as an immediate gain – at quite a remarkable value (higher than the organic revenue of the company!). It is worth noting here that according to IFRS every badwill is treated like an immediate gain through P&L. So there is nothing wrong with the accounting proceeding, assuming that there really is such a badwill – so case (1) and (2) are covered by the accounting proceeding (though not necessarily from an economic point of view. But case (3) is still open.

Source: Cyan AG, Consolidated Annual Report 2018, p. 23.

In order to assess the real quality of this move – and to understand in which case (1) to (3) we are probably located – we have to dig a bit deeper into the typical technical proceeding in a purchase price allocation (PPA). It is enough to focus on the revaluation of the two intangible assets – software etc. and customer relationships – because these are the most interesting ones in our I-New analysis. Here we go:

- In a PPA, the valuation of such intangibles (assuming that they are seen as intangibles according to IAS 38 in the first place – which btw can mostly be assumed for customer relationships and software etc.) follows the rules of IFRS 3. The respective value category is the “fair value”, which usually is seen as “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date” (IFRS 13).

- This fair value can be basically determined according to three different valuation approaches: (1) the market approach looks at active markets for the asset or comparable assets. We can exclude here that an active market or market indication exists for customer relationships (by nature in most cases) or for the relevant software (if so, Novomatic would have sold the software directly at a positive price). (2) the cost approach is based on the idea of rebuilding the asset and to determine the costs associated with the rebuilding. As still the overlying idea of a potential “transaction” is inherent to the fair value measurement, the cost approach only makes sense if it is a good proxy for this potential transaction price. This makes this approach usually not very well applicable for customer relationships (you can spend a lot of money to build up customer relationships but still customers do not want to buy your products) and only applicable for software if really an asset is generated that has a transaction value of similar size. So, when applying the cost approach it is always necessary to not lose sight of the potential future cash flows that the asset generates. This brings us to (3) the income approach which clearly looks at the potential future benefits that someone can earn from holding the asset. For our case of customer relationships and software there is usually always (at least) a link to this income approach necessary.

- The income approach itself knows a couple of sub-methods. Without going to deep into this they mainly differ in terms of whether the whole company is valued at first (e.g. using a DCF) and from this the value of the other single asset is deducted to the value of the intangible asset under discussion, or by directly valuing the expected cash flow stream of the single intangible asset (just as a comment here: the so-called relief from royalty sub-method which looks at a potential income from licencing-out the asset can also be excluded here because if one could do it, Novomatic would have done it already).

- So in this particular PPA it is highly probable that the buying company Cyan as well as the auditors had to build their own expectations of future cash flows relating to the company as a whole or the single assets in order to come to a conclusion on the value of the assets – by doing this they always had to keep in mind that the benchmark is the price for these assets in an orderly transaction.

Looking further into the specific transaction, Novomatic did not seem to be a forced seller of the I-new subsidiary. Perhaps a bit bored by it but far away from throwing it into the market at any price (and the above presented numbers on I-New’s historical performance support the assumption of a basically zero purchase price). This makes case (1) highly unlikely in this transaction.

So, now you should have enough information on this case to think yourself. Why does Cyan and Deloitte Austria see so many positives in the customer relationships and the software if the long-term owner didn’t see it? They should have performed a future oriented subjective valuation (income approach) of these assets. And: Against the background of the zero-price-transaction which took place immediately before the PPA, how strong must the conviction have been for Cyan and Deloitte Austria in order to override the results of this transaction just by own expectations of the future? How reliable are such own expectations against the background of conflicting market information? How does their opinion fit with the current development of extensive restructuring activities of Cyan relating to I-news (source: Cyan H1/2019 report)? What exactly are their assumptions on an ‘orderly transaction’ which obviously is seen as differing from the real transaction?

What Cyan and Deloitte Austria gave here is a bold statement against the real transaction price. It is a clear message that they feel so convinced by their own view on the business that even real world information points do not matter for them.

To make one thing clear: it could well be that everything is ok with this proceeding. But for an outside investor this is not at all retraceable without more information – and the risk of being the victim of a false valuation is very high here. In fact, his proceeding differs a lot from a usual proceeding in a PPA. And in such a case prudent investors simply cannot relate on the pure result of the PPA, they definitely need more input on this market pricing override. Hence, investors would well be advised to:

- Request more information on how Cyan and Deloitte Austria came to their assessment (this would help a lot in building up an understanding about the future performance of I-new).

- Track the performance of I-news closely over time in order to get a better understanding of how credible Cyan’s and Deloitte Austria’s assessment was at the time of the PPA.

As a final remark, we also do not want to hide here that we were troubling also with the quality of the data provided by Cyan (which does not make things any better). In a press release at 1 July 2019, Cyan announced that the company has published on a voluntary basis a “geprüften Konzernabschluss” (press release only available in German, “Konzernabschluss” equals “Consolidated Financial Statements”) for 2018, together with a link on where to find this document. Usually, in German language, “geprüft” Consolidated Financial Statements is the expression for “audited” Consolidated Financial Statements. However, we could not find any auditors’ opinion in the respective documents (at least in the ones we have found). Probably, “geprüft” refers to some other sort of certification or review (e.g. internal ones) but this is something one would not really expect reading the press release. What remains here is that there is no visible auditor’s activity or opinion in the respective report that we have found on the website (see HERE).

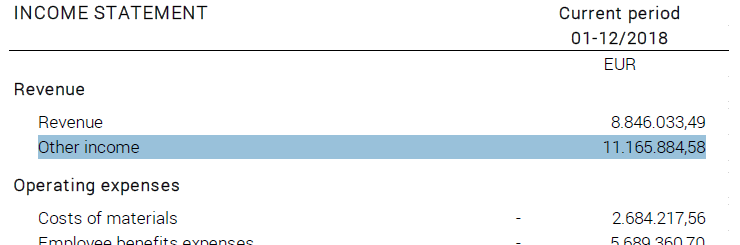

We are also not super happy with the disclosure of the badwill-gain – even if it would be seen as correct to treat it as an immediate gain. It is listed directly under the header “revenue” while it is certainly not a revenue at all. But at least it is marked as “other income” in a sub-category of revenue. This makes this disclosure definitely a bit better than e.g. the disclosure of e.g. Drillisch AG after its acquisition of yourfone retail AG in 2015 where the badwill gain has simply been included into revenues without any further explanation.

Source: Cyan AG, Consolidated Annual Report 2018, p. 16. Comment: the badwill gain is part of the “other income” category, there are also some minor, other research subsidies included in this position.

To summarize:

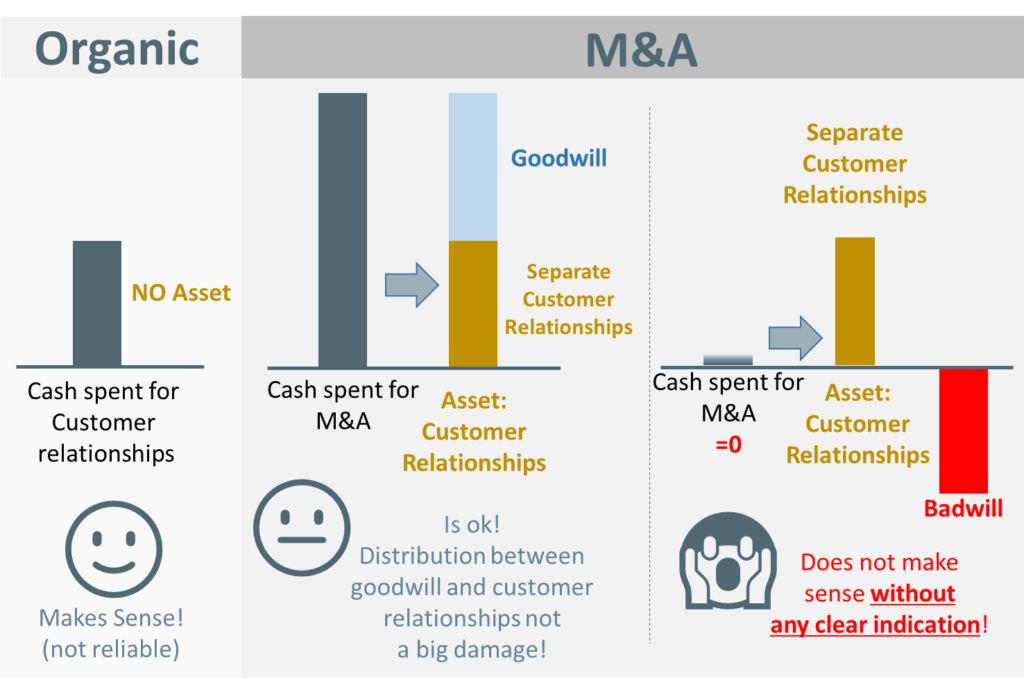

- The basic idea of the PPA (to bring some net-assets onto the balance sheet that one could not bring onto the balance sheet without an M&A transaction) only makes sense from an economic point of view if there is a positive price being paid for the new net-identifiable assets. A good indication for this is if the purchase price in the whole transaction is positive – and then it can be broken down to the single net-assets.

- The damage of a typical PPA proceeding in the context of a positive (equity-equal) price being paid – namely that by application of the income or cost approach some assessment on the future cash flows and risk on single assets is subjective and might be wrong – is manageable. It is just a distribution of a given amount of money on different assets. Although, it is not the topic of this post to criticise the PPA in general, we still want to highlight that “manageable” does not mean that the typical PPA proceeding is a good one from an investor’s point of view. The split-down of net-assets in a PPA still has consequences on the future amortization figures. But this is up to a separate analysis in this blog.

- If there is NO positive price being paid for the total net-assets, there is still a possibility to assign a positive value for some net-assets. But then a buyer absolutely MUST be able to determine the value of the single isolated net-assets on a super-highly RELIABLE basis. In other words: It must be absolutely clear for which assets which price has been paid. The normal rules of PPA (e.g. amongst other to determine the value based on some subjective cash flow and risk estimates) are not at all reasonable here. It is no longer a distribution of price, it is an out-of purchase price value indication. The risk of generating assets just out of hot air (with an accompanying immediate gain in the P&L) is simply too high.

- Whoever generates a badwill should – at our opinion – not only rely to IFRS 3.36 (“Check twice!”) but clearly disclose the basis of the revaluation of single assets. If he/she cannot do this or doesn’t want to do this (e.g. for competition reasons) he/she cannot show an immediate gain in the P&L (at our opinion, from an economic point of view) because otherwise the whole basis of historical cost accounting could be easily eroded (at least temporarily) just by doing bad acquisitions.

- Admittedly, IFRS standards are a bit weak in this whole regard. Although they have a basis in an assumed proper valuation of the net assets in a PPA, they do not set enough incentives for ensuring a high quality of the valuation. It is too easy for companies to move the limits of rule-based accounting application in the desired direction – with quite some attractive outcomes.

I think you got our doubts! We do not state that the proceeding is wrong in economic terms but we feel a bit uncomfortable here. Of course, we will be super-happy if all the assessment of Cyan and Deloitte Autria regarding the revaluation of I-New proves to be correct. But we are also going to track this closely in the future…. The 2019 annual report will tell us much more on this issue!

Disclaimer: As always, we hold no economic stake in any of the companies involved in this blog post – in whatsoever direction. We base our analysis on imperfect information and hence we might be wrong with some conclusions. This is just our subjective view and no investment recommendation at all.