In one of his latest posts, Aswath Damodaran put his fingers on a quite interesting side-effect of the well-known Softbank/WeWork story. Could it be that Softbank simply bought into the struggling WeWork company again in order to prevent any impairments for this asset (LINK)? The argument is that no-reinvestment or an investment-at-a-lower-price would have led to a presumed accounting “fair” value of WeWork much lower than Softbank’s carrying book value – with the consequence of the necessity for a write-down for the WeWork stake, and hence highlighting clearly the loss in value of this investments in the Softbank books.

What stands behind this idea is a very special understanding of reporting standard setters and other portfolio valuation regulators: If there is a “fair” transaction pricing, even for a small part of the whole asset, then one should assume that this transaction pricing is a good indicator for the value of the asset-as-a-whole. A partial pricing is representative for the total asset value: Or “Pars pro Toto”, as the Latin saying goes!

This “Pars pro Toto” application has many different faces and happens at different participation levels. Below we want to restrict our analysis to a special case of financial accounting of companies that report according to the basic set of IFRS or US-GAAP and where the profit & loss statement is involved: The change of accounting treatment of participations because of the touching of certain classification limits. In simple terms, such reclassification takes place in both major reporting standard systems if participations change their nature from financial assets to at-equity accounting or from at-equity accounting to full consolidation (Softbank’s accounting is a bit different even if it stepped up from roughly 30% up to roughly 80% ownership in WeWork with its recent move, for didactical reasons we do not want to go deeper into this particular case below). Or – important – the other way round! Hence, for a P&L-impact-willing management companies often have to step-up or -down over one of these reporting lines. As we will see, the distance to these reporting lines for each single asset determines the price that has to be paid by management for its own non-value benefits (more on this below) and it serves as critical decision making variable for investors.

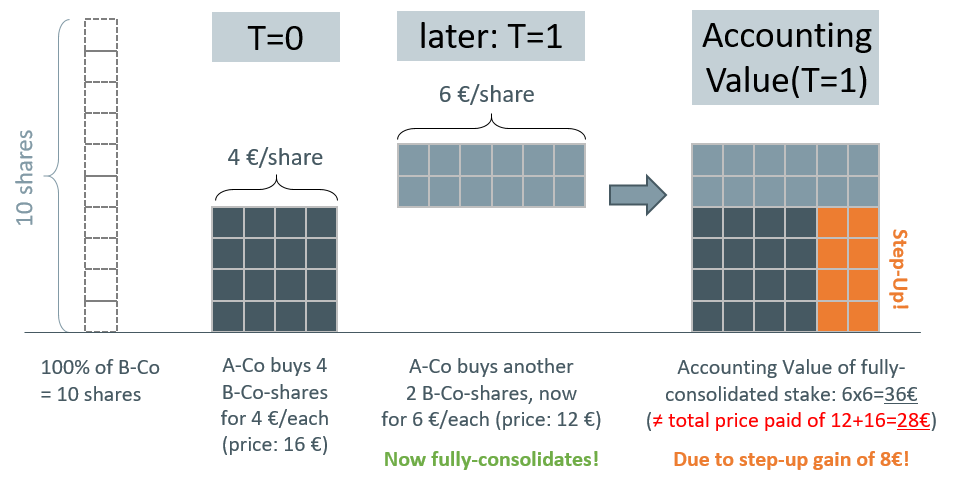

The above graph should clarify the basic problem for a typical step-up acquisition where the buyer-company A gains control in its participation in company B. Here, company A originally (T=0) buys 40% of company B for 16 Euros and accounts for this as an at-equity participation. At a later point in time (T=1) A buys an additional 20% of B for now 12 Euros and can now fully consolidate the stake. The trigger for the accounting valuation after the second transaction is the recent price paid (12 Euros for 20%) and this entails a fully consolidated 60 Euro for 100% (because the new “Pars” stands benchmark “pro-Toto”: 12∙1/(20%)=60 Euros) or – after controlling for minorities – a 36 Euro value for the 60%. This differs from the sum of the consideration given over time which is 16+12=28 Euros. The difference is here the step-up gain of 36-28=8 Euros.

Admittedly, at first glance such thinking makes quite a lot of sense in a basic theoretical setting (a current market pricing is still a very strong fresh value indication for the whole asset), but there are two major problems with this:

- Even if the underlying valuation theory was right, such proceeding offers a lot of room for manipulation or at least a lot of risk of economic misrepresentation. Admittedly, a clear misleading of investors is extremely difficult to spot here for an outside analyst without any deeper analysis (and we certainly do not want to blame any company if we do not know with a sufficient degree of certainty). But at least we can state that the risk that companies might behave opportunistically is very high here.

- Additionally, the underlying valuation theory is already wrong in the first place in many cases. It is too simple for our real world valuation cases and not in line with what we know about valuation concepts. This is a big misunderstanding of standard setters, we think, and it certainly adds to investors’ confusion.

To start with the first point, the pure practical problem of this “Pars-pro-Toto” rule is that the pricing of the partial transaction is perhaps in reality not so “fair” as one might expect, even if it takes place between two independent parties. Perhaps one of these parties’ management is willing to sacrifice a fair pricing, i.e. tolerating a worse transaction price for its shareholders, at the benefit of some other advantage for itself, such as the prevention of a write-down of the whole position (as in the Softbank/WeWork case suggested by Damodaran), the better resemblance of the value of the whole position (a high value looks always better than a low value) or even a management bonus- or guidance-related more attractive outcome.

Of course, the price-to-be-paid by such a non-fair transaction for the sacrificing party’s management is the loss in the economic value of the asset-position that comes along by entering in a such a bad transaction. This price is often too high for full-asset or full-position transactions. That is why we rarely see intentional bad transactions for whole positions, at least if the parties involved are really independent (important: see about the problems of transactions between not fully-independent parties HERE and HERE). But this does not mean that we never see such strange full-asset transactions at all, we have a couple of evidence that this also happens from time.

However, in the simple “Pars-pro-Toto” case the price is often not very high. Nobody sells or buys the whole position here, it is just a smaller part of the position which is subject to the transaction. And the economic loss for only a part (and perhaps only a very small part) of the whole position might certainly be seen as adequate for some managers to be compensated by the other benefits mentioned above. Putting it differently, the probability of a management’s motivation-arbitrage obviously increases with the smallness of the effective transaction that triggers the revaluation of the whole position.

With these explanations we already touch an extremely important Corporate Governance aspect. While there might be possibilities for management to cover one bad (economic value loss) by one good (better resemblance, no write-down, higher bonus, etc.), the outside investor loses twice: he or she suffers from an economic value loss AND from a loss in transparency or reliability of the stated numbers. This double-suffering is why it is so important to look closer at this topic.

And the problem is not only restricted to step-up situations. It is also possible to play this game by reducing a certain investment position to the lower level (a step-down transaction). While this might look odd for some readers at first glance – because managers would need a transaction partner that is willing to pay a higher price than economically required – there are sometimes some strange side-agreements in the contracts which officially (ongoing consulting fees, certain take-or-pay contracts at attractive conditions, etc; which are handled separately form the transaction itself) or unofficially (outside of the eyes of investors) serve as a compensation. It is important to not underestimate this “step-down” possibility because it can often be conducted at a relatively low degree of overall economic pain for the management and for the competitive situation of the company.

We do not want to provide examples for these situations here as they all require a deep case-by-case analysis. But rest assured that we have screened a couple of transactions where we really felt anything but comfortable about the above highlighted problem in recent years.

So far, so good (bad), but now let’s move to the pure theoretical problems (bullet point [2] from above). Even if managers do a step-up transactions to the best of their knowledge and belief, and by paying a fair price for this partial position, the step-up rule is still flawed in many cases. We want to highlight this point by making use of one of the most controversial step-up applications in recent years (at least to our knowledge): The Carlsberg-Lao accounting!

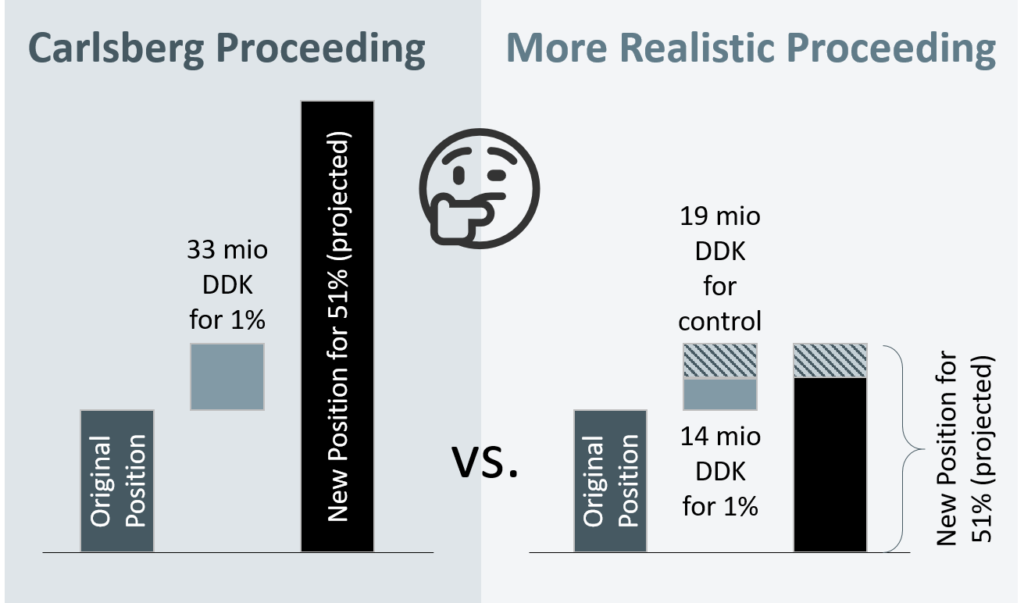

The Danish Carlsberg A/S is one of the biggest brewery companies in the world. Before 2011 it held a 50% position in the Lao Brewery Co. Ltd which was proportionally consolidated. Then, in Carlsberg’s 2011 annual report it is written on page 6: “The Group acquired an additional 1% of the shareholding in the joint venture Lao Brewery Co. Ltd., Laos, in a disproportionate capital increase, thus gaining control of the entity in a step acquisition.” So Carlsberg went from 50% to 51% ownership and now can fully consolidate the asset! On page 66 of the 2011 annual report, note 30 (Acquisition and Disposal of entities), Carlsberg gives more information on this move: Carlsberg brought-in assets valued at 33 mio DKK in order to get into the desired control position. The accounting values of Lao before and after this transactions look as follows:

| Before | After | |

| Consideration given | 33 mio DKK | |

| Accounting Value (assuming 100% ownership) | 1,372 mio DKK* | 33*100=3,300 mio DKK |

| Book Value for the 50% (before) and 100% (after, fully consolidated) ownership position | 686 mio DKK (50% of above) | 3,300 mio DKK (100% of above) |

| Step-Up Gain (Carlsberg accounting, after accounting for non-controlling interests) | 3,300*51%-686=997 mio DKK

|

|

| Effective Accounting Step-Up Gain on the original position | 997*50%/51%=977.5 mio DKK |

*according to Carlsberg accounts

Obviously, with this transaction, Carlsberg created an increase in the like-for-like book value of Lao assets of 977.5 mio DKK (>140% of the original 50% value of the Lao position) even after controlling for the increase in ownership in its position – just by this 1% step-up transaction. Quite a lot!

Just as a short reminder: You can also see here the relevance of this transaction for the above described practical application problem: It takes only a 1% step-up for Carlsberg to massively revalue the whole position (or in money-numbers: only 33 mio DKK for an adjusted step-up gain of 977.5 mio DKK). Without any more explanations here, obviously this highlights that the risk that something has not been followed a fair transaction situation is quite high (but it is still possibly reasonable). But we rather want to focus on something different here.

In fact, the big conceptional question is: Could it perhaps be that the original book value for 50% ownership in Lao is quite a good measure of the fair value AND the additional consideration given for reaching the 51% threshold is a fair amount, TOO. This would confront with Carlsberg’s accounting proceeding as obviously the new transaction generates a totally new total asset valuation and renders the old valuation obsolete. And here the answer to this question is…. Yes, this could very well be!

The reason for this is that after the transaction, Carlsberg has full control of the assets (something it didn’t have before). And control has a value! Now Carlsberg has totally different possibilities of influence on the Lao assets than before. We know that control has a value from investment reality but also from academic research. So perhaps (and this is not at all only an hypothetical exercise) Carlsberg was willing to pay just the original per-% value of 1,372∙1%=13.72 mio DKK for the controlling-adjusted increase in its participation (absolutely in line with the original value) AND additionally was willing to pay 33-13.72=19.28 mio DKK for getting control of the assets (you only pay a control premium once and for all stakes you have in the company, you cannot transfer such a premium to each and every percent of you holding)? This would make perfect sense from an economic perspective. And this would totally change the whole situation.

Now the implied value of the 51% position as seen from Carlsberg is 51∙13.72+19.28≈719 mio DKK (or the consolidated 100% position at 100∙13.72+19.28≈1,319,28 mio DKK – we abstract here form any further control premiums that might be relevant once Carlsberg gets direct access to the cash flows of Lao). Now the accounting step-up gain is just the 719-686=33 mio DKK and the “economic” step-up gain would be (719-19.28)∙50/51-686=0 DKK – no step-up gain at all (and that is logical in this setting here)! Clearly all these values differ massively from the Carlsberg accounting proceeding.

We do not want to discuss in-depth what exactly the thinking behind Carlsberg’s transaction price for the additional 1% was. But the here presented “control-premium” concept makes a lot of sense, we think. It could be that the thinking of Carlsberg was a mixture of both – overstating and control – or even something else (as some investors suggested at that time). With “something else” we mean that it could also be a LOWER market price for the 1%-stake (entailing a lower fresh value for the original position) combined with an even HIGHER control premium. However, for those who want to follow this latter possibility (e.g. because control premiums often are in the region of ca. 30%, much higher than the here assumed one): we want to slightly calm you down here. Carlsberg already was in a strong decision making position before the transaction (joint venture) and so a price of 19.28 mio DKK does not seem fully unreasonable for the next control step – but this does not mean that those investors with extremely critical eyes are totally wrong with their assumption of a higher control premium. It would need some further research to find out (something we have done at that time but we do not want to disclose our findings here). In any way we can see: What a difference a control premium can make for fair values of partial positions!

Carlsberg is not alone with such accounting effects. A similar jump just to 51% control-ownership (although from a lower starting level of 20%) had been observed for New York based TV company Discovery Inc. (at that time still operating under the name Discovery Communications), which recorded a step-up gain of 29 mio USD on the before non-controlling stake in the course of bringing its Eurosport-participation to a controlling position in 2014. In this year the Discovery company showed an overall net profit of 1.1 bn USD, so the accounting effect was just marginal but still existent.

And an example for starting at the just-below-control level but now to a much higher new ownership level is the following one: In 2018, Australians biggest fresh fruit and vegetables company Costa Group increased its holding in African Blue, a Morocco-based blueberry grower, from 49% to 86%, i.e. also stepping from a pure joint venture position up to a control position. This allowed Costa Group to book a step-up gain of 48.3 mio AUD on an originally valued 21 mio AUD African Blue position. Here again for accounting reasons any control premium paid was just taken down to the revaluation of the non-controlling stake. Admittedly, in this case a potential control premium distributes a bit better over the freshly acquired stake (as a bigger percentage was purchased) but the basic economics are still similar to the Carlsberg/Lao case.

Diageo plc., one of the world’s biggest producer and marketers of spirits and other alcoholic beverages, even benefited twice from the control-premium effect when building up its position in United Spirits Limited. In the financial year 2013/14 (FYE 30 June) it recorded a step-up gain of 140 mio GBP when moving from a financial instrument to at-equity accounting (which included presumably at least a soft control-premium), and in 2014/15 of 103 mio GBP when bringing the participation to a fully consolidated one. This was also not super-material vis-à-vis a net income of ca. 2.2 and 2.5 bn GBP in both years, but it still was a nice little sweetener.

And so we can find many other such examples: some more, some less material but all benefiting from the control-premium effect on their previously non-controlling (or softly-controlling) stakes. Such accounting proceeding is really against all valuation and pricing reality that we know. It is a basic misunderstanding of standard setters to go this way. So it definitely has to be taken into account in investors’ analyses in every step-up situation!

As a checklist: At our opinion, for investors the following points are important to check if confronted with a step-up- or step-down-gain:

- Check if there are any indications of a non-fair transaction. Are there any side agreements that come along with the transaction? Is there are forced-seller or forced-buyer situation at the other side of the transaction? Is the transaction seemingly away from market pricing of comparable assets? Of course, auditors also check for this but they also often follow some rules and limits. Perhaps the limits are stretched just as wide so that auditors agree but investors would not.

- Be particularly wary if only very small transactions take place which are just enough to move the position over one of the participation accounting hurdles. Here the risk of misstatement is highest.

- Repeated step-up- or step-down-gains can also be observed if it goes in-line with the contract length of management. Why pushing everything up in one period when management can distribute it over more than one period and benefit from this effect on a seemingly sustainable basis?

- What is the value of “Control”? This is a difficult question. The answer heavily depends on the market environment as well as the single transaction circumstances. But it is worth to think about it deeply when looking for the real fair value implications of transactions.

- We have seen some companies in trouble (or companies with participations in trouble) that apply such techniques simply to highlight the (in fact non-existent) substance in the respective positions. Take particular care in these situations.

- There is also the situation of a step-up- or step-down-loss. This is sometimes the case if companies perform a “big bath” accounting. Why not driving the values down just to benefit from the low positions only in later periods? This is also something we have observed in the past.

- Sometimes these transactions are just used to highlight the real value in the assets. There is nothing wrong with this, just a new set of information (as long as none of the other above aspects are touched).

To summarize: Step-up or step-down accounting value implications are a real weak spot of financial reporting. Admittedly, there are certain hurdles to go for corporate management if they want to mislead investors here: they have to go for a transaction! Much trickier than just changing one or the other assumption on some valuations. But we see this more and more often to happen these days. While a couple of years ago we just thought that it is ok to look at the really strange and obvious transactions we today look at each and every single transaction that entails such accounting effects. Companies more and more stretch the limits set by auditors and hence we have to step in as investors regularly to understand what is really behind these transactions. And not rarely our perspective differs quite a lot from the accounting picture that companies present to us. But we also have to admit that in many cases we are just lacking enough information to make a clear and sound judgement. But it is certainly always enough to move our gut feeling in one or the other direction.

Disclaimer: The observations presented in this post are just subjective and do not at all entail a clear statement that something is wrong with the accounting from an economic perspective at the respective companies. The comments should just highlight the riskiness of the particular step-up accounting treatment if seen from an investor’s point of view. Furthermore, this post does not at all give any investment recommendations for whatsoever company share and in whatsoever direction.