(English version of the VALUESQUE German blog post, 14 February 2019)

As a starting point today, we do a little math exercise: what is the expected value of a 100 Euro future cash flow, realized at an 80% probability? 80 Euros, of course! And what is the expected value of a 1.000 Euro cash flow, realized at an 8% probability? Right, also 80 Euros. The same. Not a problem for financial analysts.

Of course, everyone interested in business valuations always has to think in expected values and distributions: How likely is the occurrence of specific events? What is the distribution of the related cash flows? And: what is the range of possible cash flow realizations? Analysts have to get a clear picture of all of this if they want to reasonably calibrate the discounted cash flow (DCF) model, i.e. the cash flows themselves (the numerator in the DCF-model) as well as the risk adjusted discount rate (the denominator of the model).

Too bad, however, that our financial reporting systems can only support us here at a limited degree. Not only is the expected value thinking rather underrepresented in financial reporting – ok, one could live with that because expected values always require management discretion and such discretion is not necessarily suitable/wanted as a basis for decision making for investors – but even more severe, the balance sheet is rather a colourful hotchpotch of many different value and probability categories. A clear line is often missing and an analyst has to know this if balance sheet information should be transposed into an expected value world.

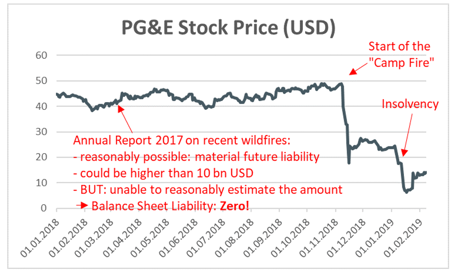

A recent practical example reveals the whole misery of this circumstance: the biggest US-utility Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), located in California, had to go into insolvency because of (threatening) legal actions amounting to billions of USD. The company feared that potential responsibilities for fresh wildfires in California would bring it financially to its knees. One reason for this is that, amongst others, it cannot be excluded that old overhead power lines of PG&E might have contributed to triggering the fires. (Comment: In the meantime it is confirmed by the CAL Fire Office that the power lines were the trigger of the Camp Fire) This is dramatic for the shareholders, of course, but not much less dramatic for the accounting system per se. Because the risk in its whole dimension was known already a long time ago, however: it didn’t show up on the balance sheet!

PG&E outlined very clearly in its 2017 financial statement, with reference to past wildfires under “Note 13: Contingencies and Commitments”, that a liability might hit the company which is clearly amounting to more than 10 bn USD (“[…] the Utility’s liability could be higher than the approximately $10 billion estimated in respect of the wildfires that occurred in October 2017[…]”), but also that an sufficiently accurate estimate is nearly impossible (“[…] unable to reasonably estimate the amount of losses (or range of amounts) that they could incur[…]”). PG&E ultimately concluded that the probability for the concrete cash outflow is too small in the sense of US-GAAP and therefore a balance sheet recognition of such obligation is not possible. Hence, they left this issue in the notes of the financial statement.

The rest is history. As wildfires ignited again in PG&E’s operating areas in November 2018 (the so called “Camp Fire”) the pressure on the company massively increased. The risk of future legal fines – which was now also pushed massively by public media reports – seemed to be on an unstoppable rise. The company announced the planned filing for insolvency on 14 January 2019.

PG&E did everything right (with today’s knowledge), at least from a financial point of view. In order to bring an obligation onto the balance sheet a third-party claim must be – according to US-GAAP – “likely to occur”. This means, according to general opinion, that the probability of payment is at approximately 80% (according to IFRS: “more likely, than not” = approximately 50% probability). The idea behind this: Not everything that could possibly happen should be recognised as a liability but only events which have a certain probability degree of realization. And for PG&E the litigation risk has not passed this probability hurdle at the time of the 2017 financial reporting.

But for business valuation certain “probability hurdles” do not play a major role. What counts is the expected value, as shown in the initial math exercise: Something very big multiplied with a low probability (NOT recognised as a liability!) can have an expected value just as high or even higher than something smaller multiplied with a high probability (this will be recognised as a liability!). But everything which will NOT be shown as a balance sheet liability will usually not find the same analysts’ attention as something that is recorded as a liability. And that is also how things were at PG&E.

If one read the notes of PG&E’s financial statement carefully one could even without the gift of clairvoyance come to the conclusion – as seen from the publication date of the 2017 annual report (February 2018) – that a) in California another new wildfire might soon to be expected, no matter which trigger, and that b) PG&E’s equipment couldn’t be modernized that quickly and therefore that c) PG&E would be at least suspicious for being responsible while at the same time its line of defence against any allegations would be very weak. In short: a noticeable aggravation of the “10 bn USD” problem was certainly not implausible.

Stock markets, however, took PG&E’s disclosure in the 2017 notes quite relaxed. Of course, it wasn’t totally irrelevant to them. Yet markets didn’t want to quite think about the whole potential extent. When looking at the stock price development of PG&E we can notice that it took until the actual resurgence of the wildfires in November 2018 that investors realized what is really going on.

The PG&E case it is surely a severe one of the financial analysis problem of ‘On’ (meaning: recognition of liabilities at a presumed 100% probability), ‘Twilight’ (meaning: recognition somewhere between 0% and a 100% probability) and ‘Off’ (meaning: no recognition at all, staying off-balance, just as in the PG&E case). But this whole problem basically runs through IFRS- and US-GAAP financial reporting like a red thread.

Looking (in extracts) at the asset-side of IFRS reporting reveals: there is a clear domination of the often difficult to be economically justifiable On/Off principle in most cases. Assets are either recognised at full value or not at all. What is unproblematic for many physical assets like machines or inventories can be a big problem for many intangible values. The classic example is here the expenditures for research and development. The rule is: basic research is not an asset under IFRS – the future transformation into positive cash flows is still too vague in IASB’s opinion. But so called ‘development’ expenditures (i.e. when ‘products’ have reached a certain maturity which makes the future cash flow generation quite probable) are recognised on the balance sheet in full. However, both approaches are not really helpful for business valuation reality. Of course, the probability of turning development-stage expenditures into future cash flows are in fact higher than turning basic research ones. But in economic reality in both cases investors will find themselves in certain probability regions which are in most cases rather far away from 0%, but also far away from 100%. In US-GAAP this problem is even more severe as neither research nor development spending is brought to the balance sheet (all ‘off’)

Moreover, if companies want to recognise tax-loss carry-forwards as an asset in IFRS they need a probability of realisation of +50%. Then they can fully (i.e. at 100% probability) show them on the balance sheet. Beneath this probability level: zero recognition. And here too, the valuation truth is clearly in many cases somewhere between the extremes. Not far back in the past the French utility company Veolia Environment S.A. had such tax-loss carry-forwards amounting to nearly 1 bn Euro on its disposal. Not on the balance sheet because of not meeting the minimum probability criterion. But for business valuation reasons they had quite a value (as the real world development of the corporate performance revealed quite clearly in the following years)!

Things certainly look more colourful on the liability side of IFRS. Financial liabilities are to be recognised at their expected repayment value as seen from the date of issuance (meaning precisely: default risk will be considered). However, if there are later changes in the expected repayment value (i.e. changes in default risk) they are usually not displayed in the value of liabilities. Exceptions do exist for companies who run parts of their liability side at fair value (usually banks or other financial entities). For them it is possible to recognise the (often seen as counterintuitive yet absolutely correct from an economic point of view) effect that the liability is getting smaller when the company slips into a crisis (see the blog post on so called “own credit gains” HERE – in German only).

Provisions should usually also be recognised at their expected value – but at the expected value as of the balance sheet date! This means provisions have a present value (i.e. a discounting component) as they always relate to future events, yet a present value calculation is mostly (in particular for short-term provisions) abstracted from which regularly leads to deviations from the real “expected value”. But not always: long-term provisions are indeed discounted. Yet, very differently than financial liabilities. Standard setters rather dictate a discount rate for accruals (instead of looking at market proxies) – and standard setters aren’t usually taking default risks adequately into account but they rather focus on on yields of high-quality corporate bonds as a benchmark. By following this proceeding, the accounting value of provisions is often shifting away quite massively from the actual expected value (see our blog post on pension provisions HERE).

At least: the often unworthy game of the past with leasing contracts is finally over since January 1, 2019. Until before it was possible to choose with a few contractual tricks if companies would like the financial commitment (and asset) to be ‘On’, i.e. on the balance sheet – so called finance lease – or ‘Off’, i.e. outside of the balance sheet – so called Operating Lease. You can guess which path companies which were rather interested in lower financial liabilities and hence a higher creditworthiness followed? Right, the operating lease! But that’s history. Leasing contracts are now coming all (with very few exceptions) onto the balance sheet, and this is definitely a reasonable development (but there are still some Topics worth being discussed in this context, see our blog posts on IFRS 16 HERE, HERE and HERE).

And accordingly we can find several more examples like the ones cited above. But to avoid a misunderstanding: Accounting limits of recognition are quite reasonable in most cases. Standard setters simply don’t want to permit too much discretion or subjective assessment. That’s financial accounting. For good reasons there will probably never be an ideal accounting system in practice. And we must accept this. Yet, there are two major BUTs:

BUT (1): as a financial analyst you surely want to know which probability measure is the basis of (non-) recognition (On/Twilight/Off) in order to transpose it properly into your own appropriate cash flow forecast. But to correctly spot this probability measure is anything but easy in many cases.

But (2): IFRS’s development in past years shows quite some characteristic of patchwork. The lines of how to apply certain probability measures when valuing assets and liabilities aren’t getting any clearer over time. I definitely have a little bit of an understanding for some of the nostalgic financial analysts who still have a faible for some of the good old national accounting systems (such as e.g. German GAAP, i.e. following the Handelsgesetzbuch HGB). There the perspective was far away from any forward-looking-approach und hence expected values in most cases, but the line was at least essentially more consistent. Analysts knew better what sort of information they got delivered from the reporting.

For the analyst this old-accounting setting meant: reading the notes, adjusting the probabilities which stand behind the On-balance and Off-balance disclosures for own purposes, and eventually set up an own synthetic balance sheet (a balance sheet which follows the valuation-relevant criteria and not according to the GAAP). When doing business valuations this synthetic balance sheet path is definitely a reasonable way – because here nobody has to adhere to the tight corset of financial reporting.

But times cannot be turned back. And hence, we have to live with what IFRS and US-GAAP deliver. So, keeping an eye on what realization probability is really behind each and every single position on the balance sheet (and of off-balance positions) is today more relevant than ever before. In particular for the big positions.