In the famous 1959 Billy Wilder movie “Some like it hot” the former Saxophone player and notorious impostor and gambler Joe (Tony Curtis) manages to make Sugar (Marilyn Monroe) believe that he is the heir of the Shell company. And since 1959 it has been a couple of times that investors felt as if Joe (or someone with a similar skill set) has in fact taken over the company – be it the giving-up of the long-term development strategy in the 1990, the oil reserve overestimation scandal in 2004 or the recent discussions about a 1.1 bn USD Shell-Eni corruption case in Nigeria.

And this time some investors wonder a lot about Shell’s lease accounting following the introduction of the new accounting standard IFRS 16 (admittedly, a topic not as severe as the ones listed above – but still worth shedding some more light on).

But let’s start at the very beginning. The new standard on lease accounting (IFRS 16) that substitutes the old IAS 17 basically brings almost all lease commitments of the lessee as a liability and a respective “right of use” asset onto the balance sheet starting in the financial year 2019 (for more details on IFRS 16, see https://www.iasplus.com/de/standards/ifrs/ifrs-16, for a working example on how this standard impacts our DCF valuation models from a technical point of view, see https://valuesque.com/deutsche-post-more-debt-same-equity-value-the-ifrs-16-financial-analysis-problem-part-1/). Two core questions are here obviously: How to determine the amount of the liability (or the asset) for IFRS financial reporting reasons? And does this make sense from an economic point of view?

A very simple example should help to understand this. Imagine a company leases a machine which has a market value of 100 Euros. The company agrees to make lease payments of 35,35 Euros in each of the next three years. The (incremental) cost of debt of the company is 3%. It is assumed that we live in a financial reporting world where the value of liabilities is determined reasonably.

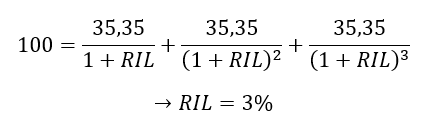

We can now determine the financial cost of this leasing contract by determining the internal rate of return of the project (the so called “rate implicit in the lease” RIL):

Here RIL exactly equals the cost of debt. Obviously in this case it does not matter from a valuation point of view whether the company a) enters into the lease contract or b) buys the asset directly and finances this purchase by taking a 3 year annuity loan from the bank at its respective cost of debt.

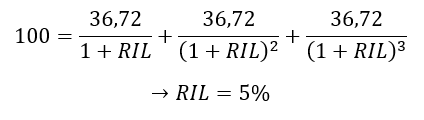

But now imagine, the company agrees to make annual lease payments of 36,72 Euros instead (all other things being equal). Determining the RIL leads to:

The RIL is now obviously higher than the cost of debt of 3%. Purchasing the machine and simultaneously debt-financing it would be the cheaper solution. Hence, one might wonder why the company should enter into such a leasing contract. Three possible reasons:

- Bad management decision; the company simply bought something expensively what it could have been able to buy much cheaper.

- Outright purchase not possible; the company cannot buy the machine directly (e.g. because the owner of this very exclusive machine does not want to sell it this way). It has to go the way of leasing it at these conditions.

- Buying more than just the asset; by entering the leasing contract the company might have bought something on top of the machine per se which has a value, e.g. some flexibility (cancellation and extension options) or some risk reduction (residual value guarantees).

Without saying too much here: In reality we most often see reason 3. But whatever it is in a particular real world case, it is worth to analyse the economic impact of all three cases below.

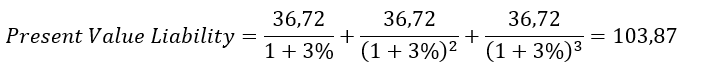

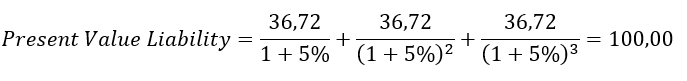

One thing is the same for all three reasons: The company makes the same payment commitments and the present value of these payment commitments is calculated by discounting them at the opportunity cost of capital. This liability side view is not at all different from the valuation of a bond or of a loan. It does not matter to whom a company owes money: nobody would value a high-coupon bond by discounting it at the coupon rate but always at the opportunity cost of debt capital). And the respective opportunity cost of debt capital is here the cost of debt of the company (3%). Hence the value of the liability is:

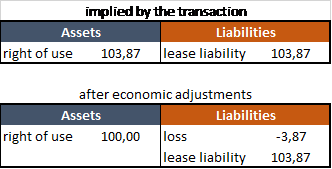

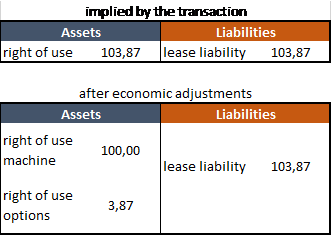

- In a financial statement world which is assumed to follow the economic perspective, the consequences for the three cases are now as follows:The company thinks it bought something worth 103,87 Euros. However, management or auditors sooner or later should realize that they overpaid (because the market value of the machine is lower) and this will lead to an impairment of the machine down to 100 Euros. This implies a loss (flowing through the P&L and then into equity) of -3,87 Euros.

2. This case must immediately raise the question on how we should know the market value of the machine here when it cannot be bought directly. Obviously, there is no real market value. The company bought something via leasing at a price a normal market participant has to pay for it. This means there are not necessarily any adjustments necessary from a financial statement point of view.

Comment: It might be that the company has to write down the asset for other reasons (e.g. lower value-in-use). This would bring us back to reason 1. But in this case the question should be asked why the company goes for such a transaction anyway if it does not make economic sense.

3. Here the company paid a fair price for a package of a) the right of using the machine and b) the benefit of some additional options or guarantees. The balance sheet should look as follows.

This is how balance sheets should look like in a sound accounting environment. However, this economic view is not necessarily the view of IFRS standard setters (it basically hasn’t been the view already before the introduction of IFRS 16, but now it becomes all much more apparent). Without going to deep into the details, IFRS 16 offers three different ways of determining leasing liabilities now at time of transition:

- Full retrospective approach (FRA): Here companies should report the leases starting in 2019 as if IFRS 16 had always existed. This is a time consuming and complicated exercise for leasing-heavy companies. Companies who go through this process have the choice to use the rate implicit in the lease (RIL) or the incremental borrowing rate for discounting future lease payments.

- Modified retrospective approach 1 (MRA 1): Here companies only take the remaining lease payment duties from January 2019 onwards into account and determine the respective lease liabilities. Right-of-use assets are set equal to the leasing liability at the beginning of 2019 (i.e. as if the leasing contract starts at the beginning of 2019). Companies have to use the incremental borrowing rate for discounting future lease payments.

- Modified retrospective approach 2 (MRA 2): The same as MRA 1, but with the right-of-use asset being recalculated back to the beginning of the respective lease contract (as right-of-use assets and leasing liabilities follow different value paths over the leasing period this implies some differences in the 2019 starting equity account [negative impact] and for future earnings [positive impact] as compared to MRA 1). Companies here as well have to use the incremental borrowing rate for discounting future lease payments.

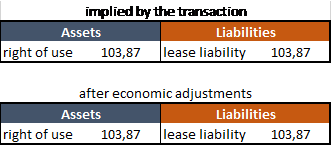

The interesting variant is obviously the full retrospective approach (FRA). Here companies can – under certain circumstances – use a different discount rate for determining the lease liability (i.e. the RIL) than the one which makes sense from an economic point of view (i.e. the cost of debt or incremental borrowing rate). Using the RIL for discounting and taking our example above, leads to a present value of the lease liability of 100 Euros:

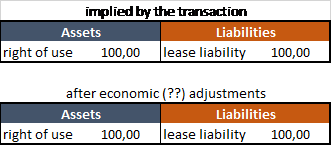

This is not a big surprise as by definition the liability (i.e. the result of the present value calculation) has to equal the asset value (100 Euros) if the discount rate equals the RIL. The balance sheet in this FRA/RIL case would look as follows:

In this case it is highly improbable that the lease liability will be upward adjusted to the economic value over time. If IFRS 16 allows for this, then it will also be kept.

When looking at the balance sheet of an FRA/RIL reporting company one immediately gets the point. The liability is understated if companies use the RIL for discounting (no matter which of the three reasons above is the actual one). It does not mirror the economic liability! Companies now look more attractive from a credit point of view than they actually are!

And companies are aware of this positive resemblance. E.g., the French retailer Casino Guichard-Perrachon S.A. which follow the FRA can now apply discount rates only slightly short of being double-digit because their Brazilian leasing activities have valuable cancellation options. The operating lease liabilities on its balance sheet are, as a consequence, much smaller than they should be from an economic point of view. And Groupe Casino is not alone.

However, not every FRA company manages to go this way. In fact, using the RIL as a discount rate is not always straightforward in practice. Some feedback that I get currently shows that for companies having opted for the FRA it is sometimes easier, sometimes not so easy to go for the RIL as a discount rate when they opt for FRA. Auditors require clear documentation on asset values if the RIL should be used as a discount rate. This is particularly problematic for companies that lease real estate (e.g. retailers) because of the non-standardization of these assets. It is less problematic for companies rather leasing more standardized assets (e.g. airlines leasing airplanes).

But not only the FRA/RIL-companies are problematic. For these companies we at least know that we have to adjust their liabilities for analytical reasons (even if imperfect information makes this quite difficult in practice). Even more problematic are companies that do not follow FRA but still own-construct their discount rates – because then it is not so obvious that we have to adjust their liabilities. And this brings us back to the original thematic anchor of this article: Royal Dutch Shell Plc.

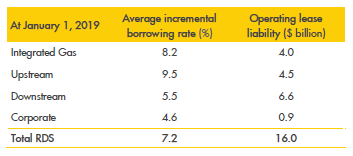

Shell presented the impact of the IFRS 16 transition in a conference call to investors dated 28 March 2019. Shell made clear that it follows the MRA, and not the FRA, meaning that it has to use the incremental borrowing rate for determining the lease liabilities. So far so good. In the call it presented the following table.

Source: Presentation “IFRS 16 update call”, Royal Dutch Shell plc, March 28, 2019 (downloaded 18 May 2019: https://www.shell.com/investors/news-and-media-releases/investor-presentations.html), slide 7.

As we can see from the table, on average the discount rate used by Shell for discounting leasing liabilities is 7.2%. This contrasts to the yields-to-maturity of outstanding long-term USD bonds of the company of 3%-4% (and for Eurobonds even lower). Quite a difference at first glance!

Of course, this comparison is not very fair. Shell enters into lease contracts via subsidiaries which might be financially ring-fenced and hence have a lower own credit quality than the mother company. But still, discount rates at these levels look very expensive. And the discussions and explanations in Shell’s “IFRS 16 update call” do not really help in softening investors’ concerns, neither (important: I have not been in the call myself; all the information are taken from the “edited transcript” of the call, provided by Thomson Reuters Streetevents).

In the call, Shell’s Executive Vice President Controller Martin ten Brink explained amongst other things the rationale behind the discount rate assumptions. He first explained, that the discount rates are a function of three considerations: the tenure of the lease contract, the nature of the assets (ultra-deep water rigs, LNG vessels and others) and the credit rating of the respective Shell entity. This already raised some questions: Why should one (at least partly) double-count asset risk and credit risk? On the one hand, asset risk is a determinant of credit risk (see the comments on the Merton (1974) model in determining credit risk: https://valuesque.com/actuarial-accounting-repair-the-pension-valuation-conundrum/). On the other hand – if you want to take it into account by determining the incremental borrowing rate – many of the leased assets of Shell should back the loan by their own cash flows which make the financing of them being largely independent of the entity’s credit rating.

Further, Martin ten Brink commented that “…the 7.2% is the weighted average incremental borrowing rate on transition. This is not an indication of the borrowing rate to be expected on future lease contracts.” and “…the incremental borrowing rate that we apply on transition is a constructed rate.” This again could not really clear the fog around these high discount rates. Is it now a market based borrowing rate or not? And if yes: why should a future borrowing rate be different then? Martin ten Brink also comments that Shell would not reopen existing leasing contracts with contract partners again in order to lower the interest rate. While such proceeding is perfectly understandable from a doing-business point of view, it unfortunately brings his whole discount rate explanation here highly closely to the RIL perspective (which is absolutely not what is relevant or appropriate for Shell’s MRA reporting approach – it is about the incremental borrowing rate and NOT about the contract terms!).

Certainly, all this could simply be a communication problem. But even after looking deeper into the annual report, I could not find any indication of such high incremental borrowing rates for the typical Shell lease project. Again of course, it could be that some rates implicit in the lease (RIL)are set at these high levels but this is not what it is about here (over and over again: Shell follows the MRA! It is about the incremental borrowing rate).

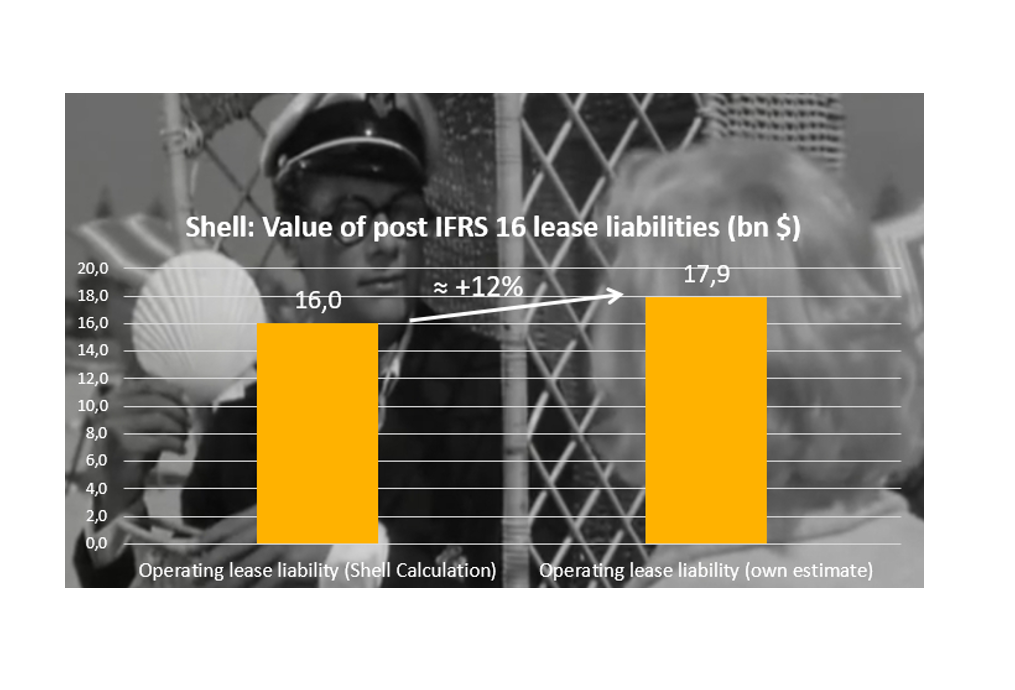

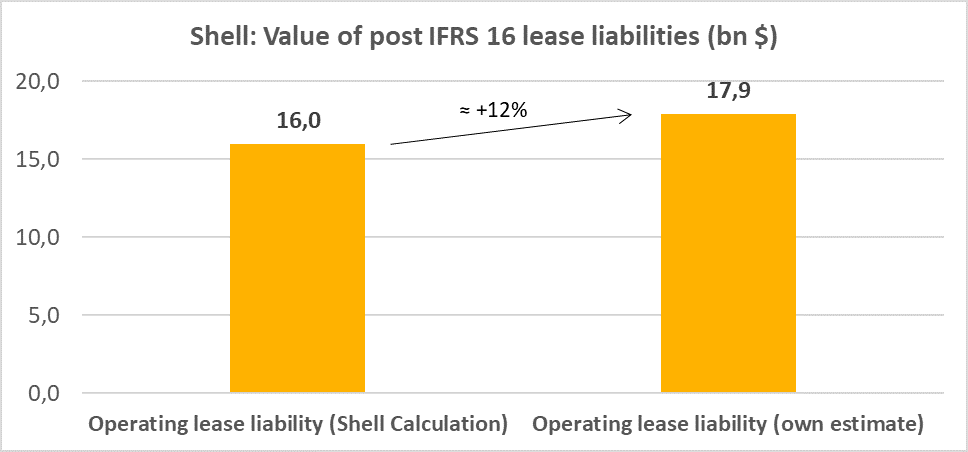

Hence, I recalculated the lease liabilities by applying some own analytically derived financing estimates (e.g. Belgian Liquefied Gas transportation specialist Exmar NV can finance LPG vessels at rates of about LIBOR plus 1%-3%, etc.). As I do not know all the details of the Shell leasing portfolio (although a lot of information had been given in the update call), I still had to make a lot of assumptions here, e.g. on different leasing durations. However, even my most conservative scenario shows some clear differences of >10% in the valuation of the lease liabilities of Shell (see graph below).

As always, what I write is not an investment recommendation and the calculations are made based on imperfect information. It is also a purely subjective view on Shell’s lease accounting. I also cannot disclose all my data sources here which I know weakens my message a lot. However, the calculations in the graph really show my most conservative scenario!

So what? Even if you have different data sources and see different results, my analytical view and also the above comments on the companies following the FRA emphasize how important it is to look deeper into companies’ IFRS 16 accounting practices regarding discount rates. Don’t take it as a given. This even more so true as this standard is new and historical comparability is not possible.

In summary, the main takeaways from first experiences with IFRS 16 lease accounting with regards to discount rates are:

- The rate implicit in the lease (RIL) is in most cases higher than the incremental borrowing rate of the company. This is mainly due to leases offering more than just access to the asset (e.g. additionally offering flexibility or guarantees). The RIL, however, is not at all a good concept for discounting lease commitments – and it has never been (not in the old IAS 17.20 neither). It does not allow to determine fair economic values of lease liabilities. This is the case if companies pay a fair price for an attractive complex lease package. But it is even more so true if companies overpay. In this latter case companies can bring the same liability onto the balance sheet (equalling the pure asset value) no matter what stupid or aggressive lease contract they enter. This does not make sense.

- It is quite strange that IFRS 16 allows for a bonus concept for companies. If you can document it, and if you go the long way of opening up again all your existing leases to follow the full retrospective approach (FRA), then you are allowed to use the RIL. At my opinion it cannot be that companies get a “liability credit” when they follow certain procedures. And by the way, the higher interest rates expense in the following years in the RIL case do not even translate into a systematically lower net income over the whole lifetime of the lease as the RIL-approach also comes along with lower than normal depreciation expenses on the right-of-use asset.

- It is also highly questionable whether companies following the FRA/RIL are doing themselves a favour by taking the RIL as a discount rate. Investors know that on a technical basis IFRS 16 does not change anything for equity values (see https://valuesque.com/deutsche-post-more-debt-same-equity-value-the-ifrs-16-financial-analysis-problem-part-1/), so beginning of 2019 should rather be the time for making a clean table on the liability side. By using too high discount rates they run danger of getting into discussions on the amount of their liabilities in one or two years’ time and then investors might have forgotten that it is still due to the equity-value-no-change IFRS 16 introduction.

- While it is to a certain degree possible to adjust leverage for FRA/RIL companies to a more economic setting, the real difficult-to-analyse companies are the ones not discounting by the RIL, but still “constructing” their discount rates (i.e. their incremental borrowing rates). This is the Shell case and I currently can see a couple of such Shell-look-alikes in the market.