When Michael Jensen published his “Free Cash Flow Hypothesis” in 1986 (‘Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow’, Corporate Finance and Takeovers, in: American Economic Review, 76, pp. 323-339) it was widely seen as a ground-breaking idea. This theory managed to bring-in a behavioural and a principal-agency perspective into a so far mostly neoclassical topic: the valuation of a firm!

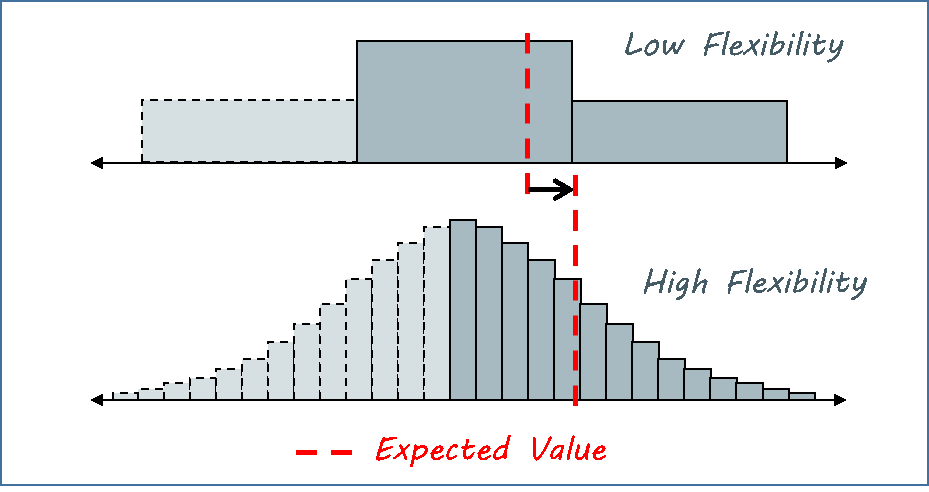

The free cash flow hypothesis says in simple words that if companies generate too much “free cash flow” managers will waste it for negative NPV projects, simply because they are not restricted to only doing good projects. The solution: Cutting down the free cash flow by e.g. high levels of debt for which high interest payments have to be made. The lower the headroom for managers the better the decision making, according to this hypothesis. Since then this hypothesis and similar measures of management flexibility have been extensively tested by academics – with admittedly mixed results but mainly supporting Jensen’s hypothesis. A very interesting recent study on flexibility found out that in particular the companies with the highest degree of financial flexibility in fact face a negative stock market performance (see Rajput et al., 2019, Is Financial Flexibility a Priced Factor in the Stock Market? in: Financial Review 54, pp. 345-375).

But these are only observations for an average or positive business environment. If companies are faced with a tough environment such as the current coronavirus-one, we have to rethink flexibility. In our current situation behavioural aspects take a back seat and hard decision-scope-oriented aspects come to the fore. We are now rather in the good old real option framework which positively prices flexibility in particularly if uncertainty is high. Even more relevant, not having flexibility is a big risk in the current environment – be it for survival, be it for adjusting to new business circumstances, or be it for participation in important future trends.

When we talk about flexibility, the first thing that comes to mind is the cash on hand and the ongoing cash generation – i.e. a simple measure of the liquidity of a company. But there is much more to it than only cash. Below we provide some aspects we think it is worth to closer look at when analysing the flexibility of companies:

- Cash and Cash Flow Generation

Clearly the most important facilitator of liquidity. In times of crisis cash is king, and the ability of cash generation keeps the business alive. When looking at cash these days, three measures are of particular interest:

- cash burn: how much of available cash (for how to treat restricted cash, see HERE) is eaten up by the business over a particular time period (e.g. one year)

- static cash runaway: how long does the available cash positions last, given a certain cash burn rate (sometimes this ratio is also called the “defensive interval” if more than just cash – i.e. also some other short-term assets or undrawn credit lines are included)

- dynamic cash runaway: how long does the available cash positions PLUS worst case ongoing operating cash generation last, given a certain cash burn rate; it is seen as very positive if dynamic cash runaway is eternal.

- Asset Disposals

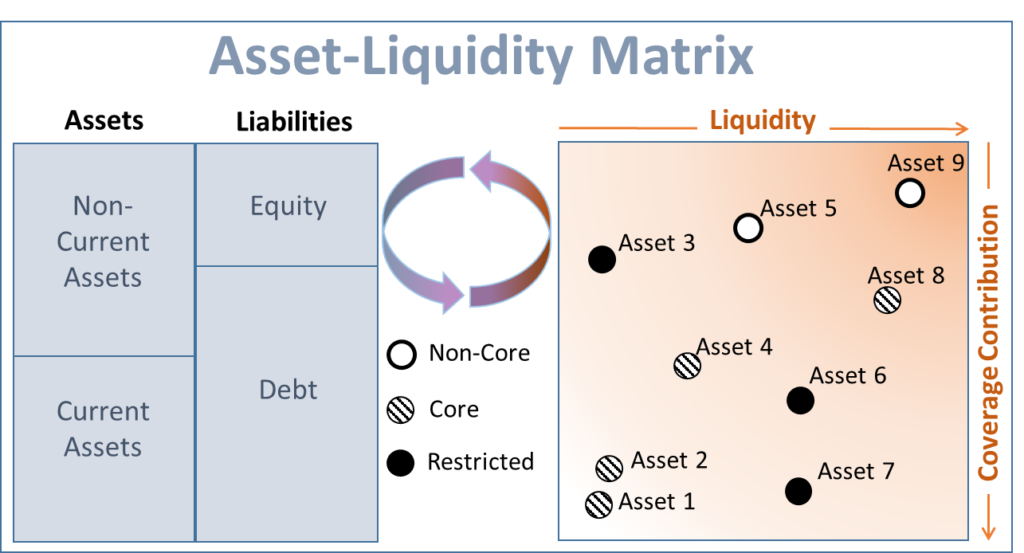

A very important driver of flexibility is the potential to raise cash from asset disposals. This does not mean that the company has to do such disposals but that there is the possibility to raise cash a) within a reasonable amount of time, b) without negatively impacting the core business, and c) without weakening the credit profile.

It is important to note that it is not necessarily the case that assets we find under “current assets” on the balance sheet are rather suitable than non-current assets. This is why it is necessary to transform the balance sheet into an asset-liquidity matrix, which takes the above mentioned criteria a)-c) into account. Based on such a matrix one can see how big the flexibility from asset disposals is for the company.

- Financial Liabilities and their structure

Financial obligations are certainly a restriction of flexibility. The most important factor is currently to identify refinancing or redemption dates (the earlier the worse) but also the financial debt composition (one big is worse than several smaller). Additionally, it is worth to understand what covenants say, i.e. at which point there is risk of renegotiation or cancellation, whether foreign currencies are involved here and whether there are some off-balance financial liabilities with tight payment terms (guarantees or debt in non-consolidated units).

- Hedging

It is necessary to review the hedging portfolio of companies. Some typical hedging contracts (often for currency risk) provide insurance only within a certain range (so called collar strategies) because this is very cost-efficient way of staying safe with a high probability. However, as market movements have been quite material in recent months it is possible that some of these hedges are no longer working. If companies now stand at the wrong side of the transaction this can materially negatively influence their financial flexibility.

- Specific Commitments

Usually operating commitments are already covered by the cash burn analysis and financial ones in our liability analysis. However, there are some payment duties which are worth to be analysed in more depth. These duties can be contractual in nature (e.g. some take-or-pay or minimum purchase commitments from suppliers which just kick-in in this coronavirus-phase), insurance-like (e.g. some guarantee payments to customers which now become relevant) or a contingency which has changed in value.

- Operating Flexibility

The most important measure of operating flexibility is the degree of operating leverage, i.e. the amount of fixed costs of a company. This is particularly business model related but within industries we also see some differences. In manufacturing business it turns out that it is positive these days if companies provide a rather low value-adding depth to the products, i.e. they rather follow an assembly model, such as German cooking equipment manufacturing company Rational AG which has most of the added-value of its products in its supply chain. In contrast, companies that have a rather high degree of vertical integration are rather inflexible.

Companies with a higher degree of outsourcing, be it temporary workers or external service providers or consultants, are also more flexible to adjust their cost structure (variabilizing of fixed costs; e.g. French construction equipment rental company Loxam SAS was even able to reduce personnel costs by about 70% in France recently due to switching to temporary/partial unemployment contracts) than companies which keep most of the costs in-house.

Current government actions, such as allowing for short-time work or rental concessions, are also clearly targeting at allowing for variabilization of fixed costs. This means that for understanding corporate flexibility it also matters in which jurisdiction (i.e. under which concrete legal framework) the company operates.

- Supply Chain Flexibility

Some companies face quite strict contracts along their supply chains and others have some optionality. We have already mentioned the minimum purchase requirements that have to be checked in supplier contracts. But there is more to supply chain flexibility. One point is the lead time – the shorter it is the better for flexibility and the lower the risk of overstocking or destocking at reduced prices. E.g. Bohoo Group Plc. and inditex S.A. only have 2-3 months lead time and hence have much more flexibility in the supply chain than traditional retailers at usually 7-9 months.

But also the possibility of volume changes along the supply chain is a clear positive for flexibility. Again, Bohoo has a very flexible supply chain in this context because of its long-time established „test and repeat“ strategy which allows to check at low quantities how customers react, in order to follow-up at large quantities in case the test has been successful.

Regional manufacturing and an optimized warehouse footprint also benefits corporate flexibility. This is a model that some companies have been building over the recent years in order to be better able to deliver more customized services and products in time. E.g. PepsiCo Inc.is currently working on this in order to allow for more different packaging, brand and flavor combinations.

And finally, companies that multi-source benefit from a higher degree of optionality vs. peers that don’t.

- Organisational Flexibility

In times of crisis it becomes evident that a decentralized organisational structure allows to make distinct adjustments of just the right size where needed. Concentrated organisations often have the problem of not being able to make granular and fine-tuned adjustments. E.g., the US-based connection products and cable company Amphenol Corp. runs such a decentralised structure with more than 100 regional managers that all have decision power within their area. By this the company has proven its operating resiliency already during the 2008 financial crisis in which its margin suffered much less than its peers. And decentralisation not only allows for very specific answers to shocks, it also allows for short reaction times.

The benefits of a more decentralised organisation during times of crisis also becomes evident for other companies. Only recently the Swiss industrial group Metall Zug AG decided to focus more on the strategic management of its portfolio companies (and less on operating influence) in order to grow its organisational flexibility in this context.

Another organisational or corporate governance topic is corporate culture. A speed-oriented corporate culture that often comes along with a high level of innovation power is of high flexibility value in times of crisis as this allows to quickly jump on new opportunities and go away from non-promising old ones. L’Oréal SA has always been such an agile company which often proved its ability to quickly adapt, e.g. by its often seen operational outperformance against competitors in new fast growing segments of the beauty market.

- Strategic Flexibility

The ability to jump on strategic opportunities as they pop-up is of high flexibility value. We particularly see companies benefitting from this that have already proven their ability of being able to actively juggle with their activities portfolio. E.g. companies that have ample experience with reshaping their product portfolios such as Siemens AG and Nestlé SA are at an advantage as they are running a quite successful acquisition and divestiture strategy since several years now and as they are always trying to keep strategic flexibility.

On the other hand, some industries will have more problems with strategic flexibility. The European telecommunication industry, for example, has been focussing on paying high dividends (and hence emphasizing their sustainable business model) for many years now in order to attract investors – some sort of a classical Jensen’s FCF thinking. However, this pay-out policy restricted management from building up a position of strategic optionality and also from consequently going for the upcoming opportunities. Now, that the industry needs strategic flexibility, many companies are not prepared for it.

- No Flexibility for the Counterpart

It should not be forgotten that the lack of flexibility of business counterparts is also some sort of flexibility value.

On the customer side, this lack of flexibility could be due to brand power (emotional effects), due to contracts (e.g. concession business) or due to the nature of products and services. For tailor made products customer flexibility is usually rather low. E.g., in the steel business companies are much better positioned in the premium segment where often solutions are developed in close cooperation with the customer and where switching costs of customers are rather high (i.e. flexibility of customers rather low). Compared to this, in the standard segment there are no such switching cots. And in some software sub-segments customer flexibility is restricted in even two ways: first, because of integration of a certain solution in an already existing ecosystem (where other solutions simply do not fit) and, second, due to induction and learning costs for new, unknown solutions.

In contrast to this, many automotive suppliers suffer from this counterpart flexibility. They have brought themselves over the years into contracts with OEMs that can be easily and materially upward and downward adjusted in volumes by the latter. Now, OEMs of all colours make use of this flexibility (which benefits them) and leave the suppliers in the spectator’s role of quickly reducing revenue declines.

- Capex

Capex necessities are a double-edged sword from the view-point of flexibility. They clearly have to be seen in the context of the financing situation of the company. On the one hand, not having fixed asset investment commitments is a positive for financial flexibility. However, often the lack of such capex commitments has its roots in the fact that the company has engaged in a capex program in the periods before, thereby having locked-in a certain asset structure which now reduces its strategic flexibility (the company cannot easily adapt its asset structure to the new environment).

Therefore, the best situation is a strong balance sheet and a low number of legacy assets. Then the company can position its business for new destinations. However, if the balance sheet is weak, low capex commitments (i.e. a young fleet of assets) are much better than an old substance.