In the past, we already shed some light on the problems of reading the appropriate information from segment reportings of companies, but more in a general way (LINK). This time we provide a concrete example of why understanding segment information is highly important when performing business valuations. Here it is not an accounting problem and it is not a bad-disclosure situation. All relevant information is available in our today’s case. The company does everything correctly. Nevertheless, investors have to use each and every piece of information on segment performance in order not to run into severe valuation problems. This blog post is about Continental AG (Conti), a German automotive supplier.

Conti is a multi-activity supplier. It is structured in five segments: (1) Tire (producing car tires), (2) ContiTech (provides smart solutions made of rubber, plastic, metal and fabric to the automotive industry but also other industrial customers), (3) Chassis & Safety (develops systems aiming to improve driving safety and vehicle dynamics), (4) Powertrain (develops efficient and clean vehicle drive systems) and (5) Interior (provides network, information and communication solutions for vehicles).

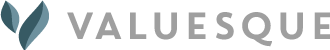

While the group in total also suffered a bit from the general weakness of the traditional automotive business in general, it has performed relatively strong in terms of fundamentals at the top-line over the last years. The following graph shows the revenue development of the group (below all group-numbers are depicted as the sum of the single segments, i.e. without taking account of any holding-level effects, which by the way are not material and do not change the general message; all data are taken from Thomson Reuters Eikon, in thousand Euros).

Obviously the activities in the main segments developed in a relatively smooth and parallel way. We want to have a particular focus on the tire business of Conti in our analysis, and here you can see that the proportion of tire sales (percentage numbers in the graph) has stayed remarkably stable over the years. But if we dig our way down towards the bottom line a bit further (Conti provides all this information) things start to look different. Let’s first have a look at the EBITDA level.

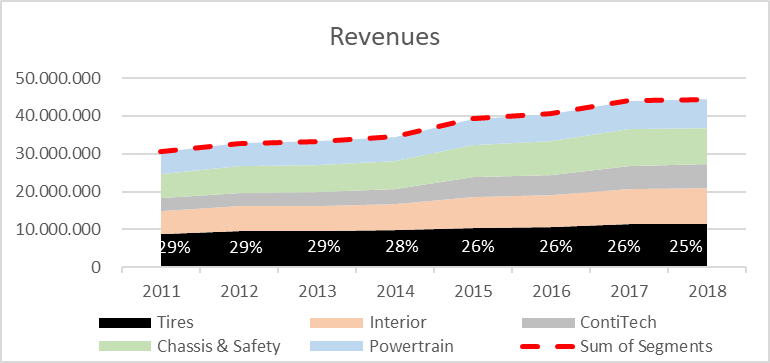

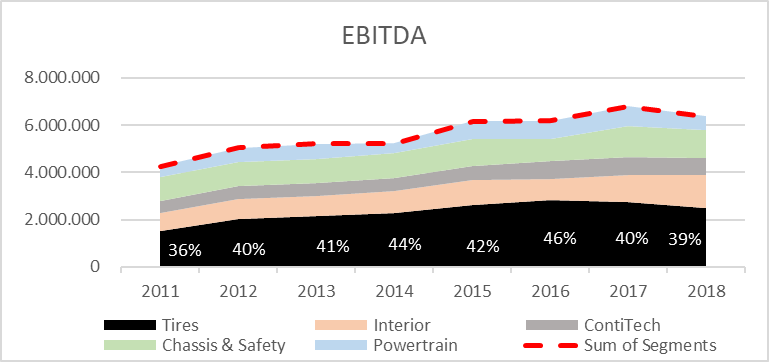

Now we can observe two interesting things: (1) the relative proportion of the tire business has clearly increased and (2) the stability of the proportions over time got lost. The reason for (1) is that the tire business is a highly profitable one. It generates margins that the other business segments can only dream of. The reason for (2) is that tires have entered into some sort of a pork cycle over the last years. While scarcity effects drove up margins until 2016, the reactions of the broad set of companies competing in the tire business (increasing capacities) kicked-in in 2017 and led to a non-immaterial margin reduction effect.

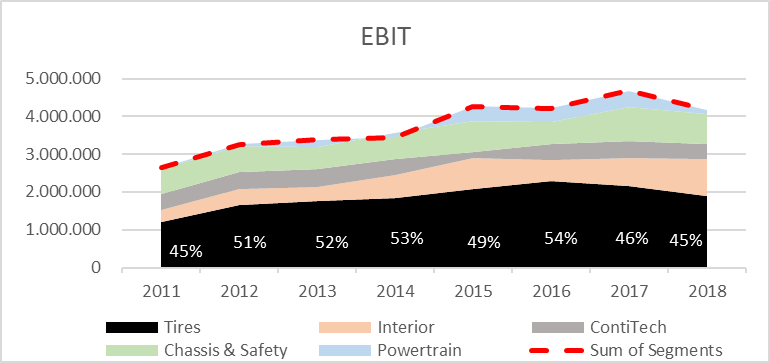

It gets even more interesting if we go further down the P&L. Now let’s have a look at the EBIT line at a segmental level.

Now the instability of the tire-business contribution remains similar to the EBITDA-level (the margin effect is relevant for both EBITDA and EBIT) but the relative contribution increases even further. The reason for this latter effect is that the tire-business is relatively asset-light in terms of how much CAPEX has to be spend in order to generate a Euro of profits – at least as compared to the other business segments – and hence depreciation and amortization charges are relatively low in the tire-business.

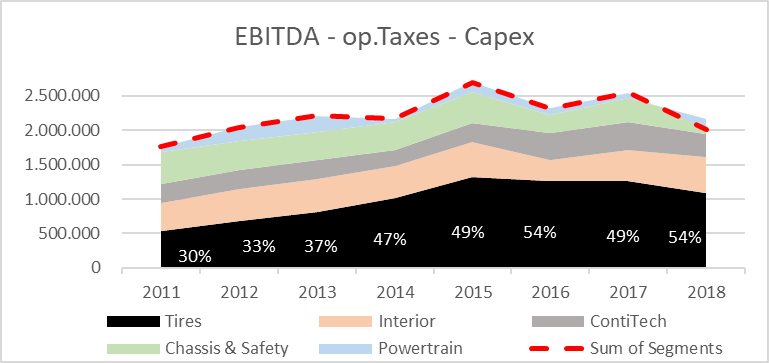

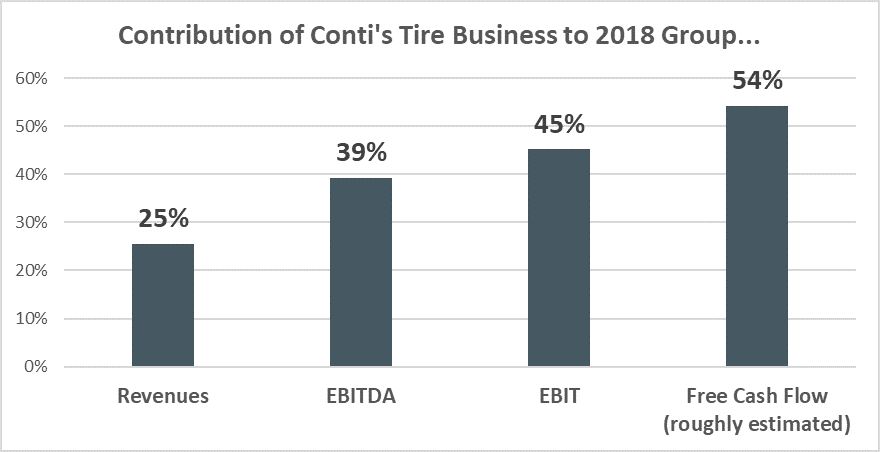

A similar picture can be observed if we look at a “dirty” free cash flow level. Below we provide an overview of a proxy of free cash flow, calculated as EBITDA minus hypothetical taxes on the operating business (calculated at a normalised 30% tax rate) minus Capex. We abstract from any working capital impact here as we do not know exactly how it is distributed over the segments. While we admit that working capital is an interesting topic for tire makers as the industry moves more and more towards a “Just-in-time” structure, and we can observe some differences in working capital management between European and Asian suppliers, we do not want to bring in any subjective assumptions here (at the cost of not being absolutely right). However, we also think that the main message of this blog post would not change a lot in the overall picture if we include working capital effects here – although the numbers might certainly change slightly.

Now we have all the data that we need for our analysis. Obviously it is necessary to go deep into the performance of the single segments in order to really find out what is relevant for our valuation. A superficial segment revenue split analysis would lead to a big misunderstanding about the real value drivers of the company. We have to look at everything that drives the cash generation of the single units – for the free cash flow at least on a normalised basis (due to the general intertemporaly instable nature of capex). And of course there are a couple of consequences for equity valuation:

- Comparing Conti with the broader universe of automotive suppliers – e.g. by the way of multiples – does not make sense on a revenue (rarely done) or an EBITDA (often the case) basis. Multiples are a proxy for a DCF-analysis, and here these two bases of reference are not an appropriate level for measuring similarity to the general performance of other supplier businesses. On an EBIT level things are, however, quite (!?) ok.

- Quite ok does not mean great! Due to the highly differing nature of the tire business from the other businesses, Conti heavily calls for at least a valuation in two parts – the tire business and the rest (at least). Better is a full sum-of-the-parts (SoTP) valuation. This is obviously the case for a multiples valuation, but also necessary for a DCF model where a separate modelling of the single segments is definitely required from an economic point of view.

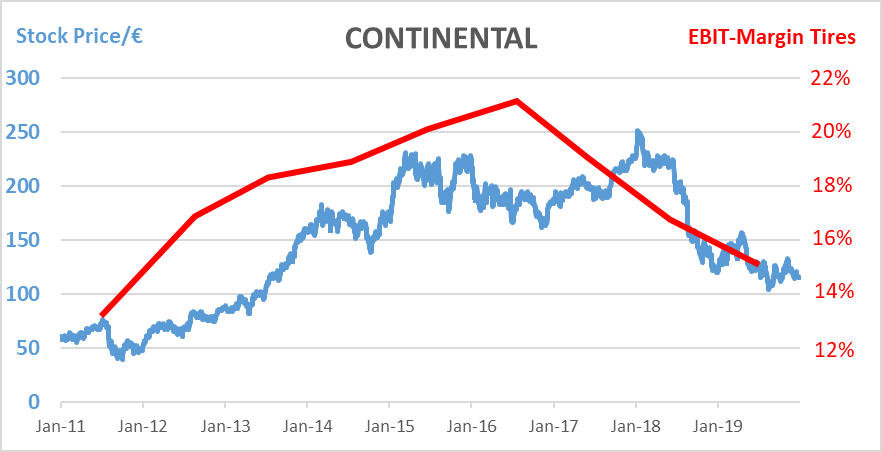

- On top of the general developments in the automotive business, obviously the margins in the tire business are a major driver of the stock price performance of Conti in recent years. And this makes sense from a fundamentally analytical point of view. Hence, analysts should devote a lot of research power to the general situation and the expected development in the premium tire market supply/demand when performing their valuations.

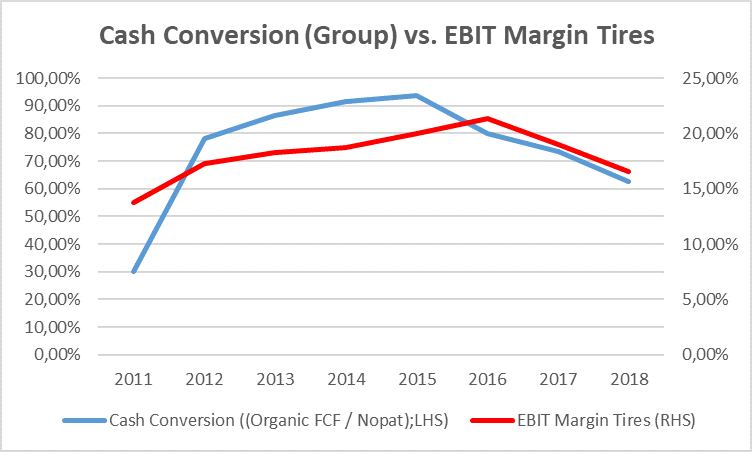

- Staying with correlations: Some analysts assign the weaker cash conversion over the last years (i.e. how Net operating profit after taxes [Nopat] translates into FCF) to the recent margin slide in the tire business. And in fact, there is a clear correlation to be observed.

Comment: Here we measure FCF by deducting organic capex from operating cash flow.

However, correlation does not always mean causality. In fact, here the step from Conti’s tire EBIT to tire FCF is not a big one. Of course, there is some sort of “leverage” to the above described effects as Capex in the tire business is much higher than the depreciation and amortisation charge (Conti tire has to invest in order to stay competitive) but the main disturbance factors are found above the EBIT line – as described above. The weaker cash conversion of recent years is rather a consequence of the massively increasing Capex in the “Chasis & Safety” (doubling since 2011) and the “Powertrain” business segments in recent years (the latter even with a negative 2018 FCF according to our rough analysis). This evidence is important as understanding the real drivers of cash conversion is necessary in order to properly project future cash generation of the company. And this again shows why a clear segmental understanding is so important when valuing companies such as Conti.

To summarize: What we have here is a nice example of where the group level is not really the best way to focus your analysis or valuation on. It is also an interesting case of why thinking through all the drivers of separate business units is sometimes indispensable in order not to get caught on the wrong foot by some of our familiar valuation “heuristics”. Of course, a DCF model is always the best academic way to value a company. But a DCF also needs a proper analysis and modeling in order to be powerful. And due to the inherent lack of humans (and computers) of making proper projections, multiples – whatever shape the take – are always an important tool for value discovery. But they have to be calibrated properly as well!