(English version of the VALUESQUE German blog post, 29 January 2019)

Properly understanding financial statements is highly important for everybody, who is profoundly dealing with practical business valuations. Whether it is about investment decisions or fairness opinions: a deeper understanding of the accounting proceeding of a company is the basis of each valuation. Often it is only a slightly changing perspective that can make a multi-billion-Euro difference, as we can see when looking at some recent developments of US-industrial giant General Electric (GE).

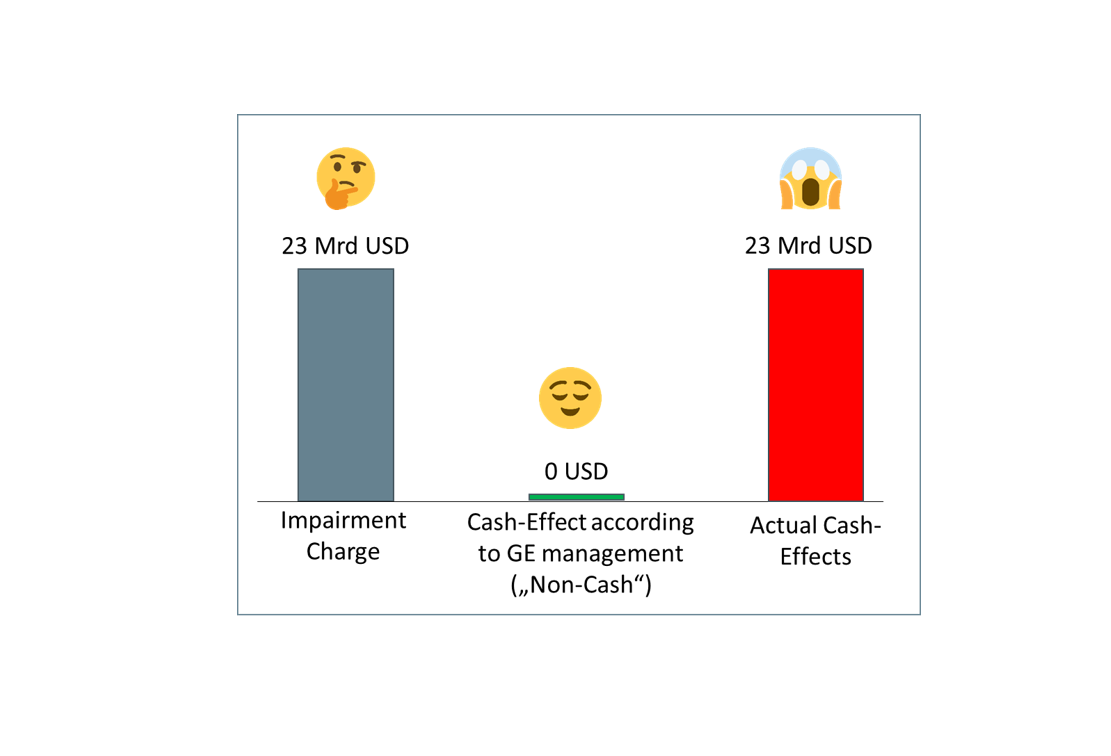

In fact, 2018 was a horrible year for GE. The company had to record a 23 billion USD goodwill write-down (impairment), mirroring the loss in value of several assets related to the acquisition of the Alstom energy business in 2015. John Flannery, who was installed as CEO just one year before, was chased out of the company and replaced by H. Lawrence Jr.

According to its communication department, however, the company did not seem to be too impressed by this development. In the 1 October 2018 press release the company send out the headline: “Company to take non-cash impairment charge related to GE Power”. Thomson Reuters articulated itself in the same vein: “The non-cash charge primarily relates to…”, just like many sell-side analysts. So, non-cash! The emphasis on this circumstance should tell addressees: No worries, it is just accounting! It has nothing to do with our cash flows – and cash is king!

And such wording is not new at all. The Deutsche Telekom AG also heavily emphasised the “non-cash”-nature of its multi-billion write-off on UMTS-licences and goodwill in 2001. In 2010, Siemens summed up its adhoc-release relating to a 1,4 billion Euro write-off in its Healthcare-Division: “The impairment has no cash impact”. In 2011, Sony explicitly clarified in connection with a 3 billion Euro write-off on deferred tax assets: „The valuation allowance is a non-cash charge and does not have any impact on Sony’s consolidated operating income or cash flow“. The Swedish automotive supplier Autoliv Inc. finally repeated the message over and over again in 2018: In the headline and several times in the text of the press release (in connection with lots of appeasing words) the company didn’t allow for any doubts about the character of its Impairments: “Autoliv records non-cash charge…” “A non-cash impairment of goodwill“, „It is a non-cash item…” and so on. And all these examples are just a small selection of many more cases with a similar message: It’s always about write-offs, and it is always emphasised that it is non-cash in nature.

However, all these corporate statements have one major problem: They have pretty much roughly the same content quality as a message from an airplane pilot, saying that all engines are broken and on fire and the plane is in free fall, but – no worries – all passengers and the crew are in good health.

First, both statements are, strictly speaking, correct. Health damage is manageable as long as the plane is still in a state of falling. And there is often indeed no major relevant cash-effect with impairments in the particular write-down period. Not even tax effects are realised since such value adjustments only appear in the consolidated financial statements.

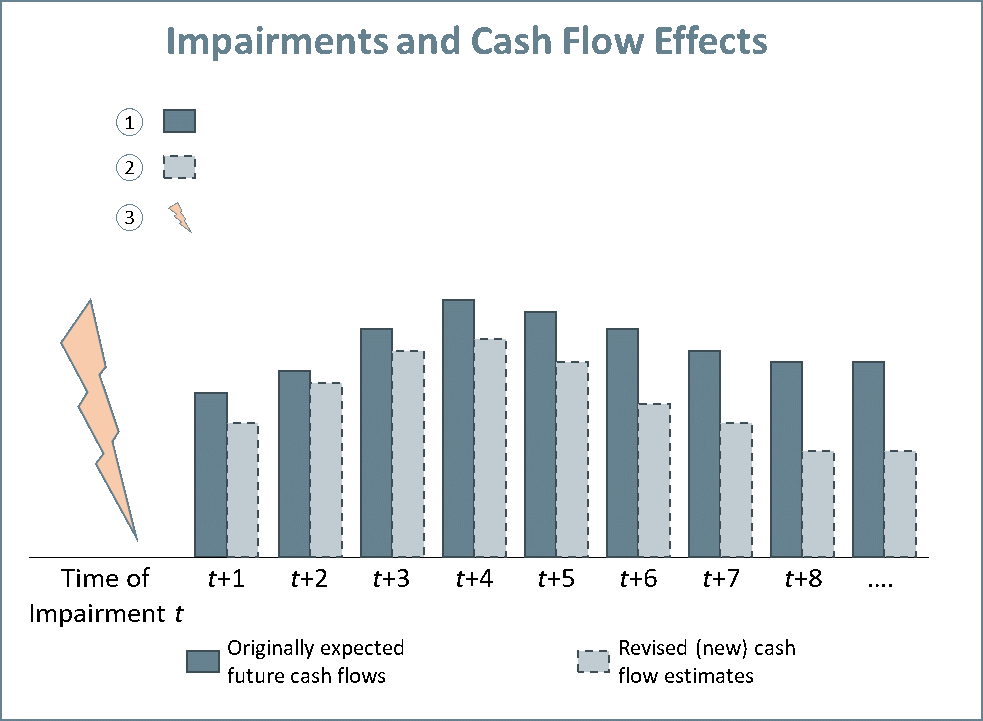

Second, the situation will most probably, in both cases, change dramatically very soon. This is obvious for the imminent plane crash. And it is not different for the impairment story. In fact, impairments are taken exactly BECAUSE the expectations about future cash flows have downward adjusted. General Electric has to write down, because the Alstom-assets will generate lower future cash flows than originally expected. And the same is the case for Siemens, Telekom and Autoliv. Sony in 2011 was confronted with the fact, that existing tax loss carry forwards were expected not to be turned into positive cash flow effects, because the performance of the country divisions will not be good enough for that in the future (from 2011’s perspective). In all cases the same: massive negative corrections of expected future cash flows (and hence: a massive future cash effect) lead to the impairments.

And third, both statements – the pilot’s and the impairment interpretation – miss the point in a quite cynical way. The current state of things is neither of significant importance regarding the well-being of airplane passengers nor regarding the cash effect of write-downs. It is without any doubt the next moments that count. And this should not come as a surprise. ‘Doing business means taking the future into account’ (“Für das Gewesene gibt der Kaufmann nichts”, already stated in 1966 by Hans Muenstermann, one of the protagonists of the development of modern valuation theory in Germany), is one of the core principles of every investment and valuation professional.

Now one might think that it is simply a minor misunderstanding between companies and investors and that companies of course do not want to lead investors up the garden path. But this is wrong! As often as we hear the emphasis of the non-cash-nature of write-downs, as rarely we hear about it in the case of write-ups. Quite the contrary! In 2015 for example, when – based on an improved business outlook – the French textile company Chargeurs SA freshly recognised a tax loss carry forward in the amount of nearly the whole annual net income as a deferred tax asset, they very actively stressed the “leading to improved free cash flows”-character of this move in their investor presentation slides.

Against the background of the highly material analytical implications of the underlying transactions, it is clear that it is of utmost importance to find the right way through the impairment information jungle in business valuation. That is why we provide a little roadmap for company valuation and financial analysis on this topic below. In general, when you see a write-down of assets, three different basic cases are to be differentiated:

- Non-Cash: A wind power station is acquired and in the following years is subject to scheduled depreciation over its useful life. In this case, the value adjustment (scheduled depreciation) takes place AFTER the cash-event (i.e. the acquisition). The depreciation does not imply any cash-consequences (apart from tax-effects). The project will eventually be finished at the end of the useful life. For valuation reasons no terminal value is calculated.

- Soft-Cash: Typically (if we do not know better), in business valuation a “going concern”, i.e. the long-term continuation of corporate operations, is assumed. In this case the scheduled depreciation/amortisation of fixed assets stands somewhere BETWEEN two cash-events. Of course, it has its root in past happenings (the initial purchases of the assets). But it also stands ahead of future replacement investments. In a company with a homogeneous asset-structure (meaning an evenly-distributed age structure of assets from young to old, and hence regular and steady replacement capital expenditures) the sum of scheduled depreciation/amortisation expenses is usually a very good starting point for an estimate of future (cash-relevant) replacement investments. Therefore, in a going concern world scheduled D&A serves as an indicator for future investment cash outflows. As the exact amount of future cash outflows is unknown today and as with future asset acquisitions there is also a ‘compensation’ in the form of (hopefully) future-future cash-inflows from operating these replaced assets, we call the cash-nature of such write-downs ‘soft-cash’.

- Hard-Cash: unscheduled write-downs, impairments, regularly have a clear and strong negative future cash-effect. The value correction of assets is happening BEFORE the cash-event. In fact, the expected negative cash flow deviations are the CAUSE for the impairment. And different from the scheduled write-downs where companies can hope for future-future cash inflows from the replaced assets, in the impairment case a company gets as a compensation for the negative cash effects: Nothing at all! Impairments are a one direction negative cash hit. Hard cash!

Of course, it is assumed here that CFOs approach the impairment testing in a reasonable and honest way, meaning that they impair assets when they have serious valuation reasons to do so, and hence follow the rules of IFRS or US-GAAP. But this is not necessarily always the case (which by the way is not a relaxation of the comments above but rather often leads to an aggravation of things). In reality, impairments are often a topic of corporate policy. We will see in one of the next blog contributions how analyst and equity valuation professionals should deal with this risk.