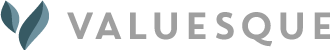

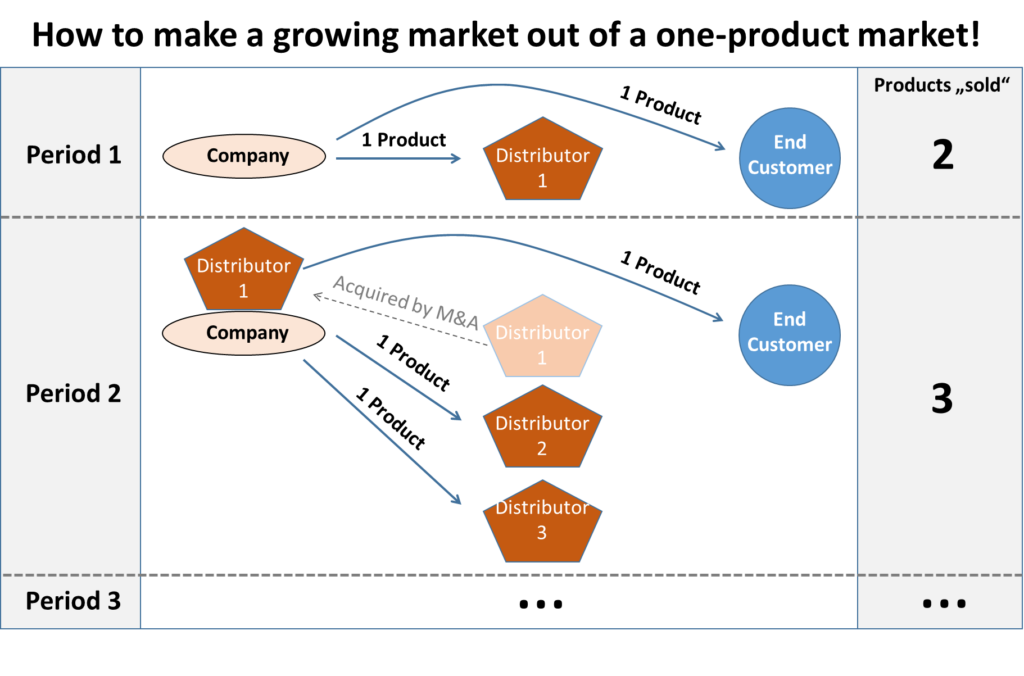

What can companies do if the end-customer market is simply too small for their ambitious revenue goals? They can simply create a new parallel-market. Sounds impossible? It is not! And it has already been applied (or at least tried to) a couple of times in practice… Let’s explain this technique with a simple (and simplified) example. Imagine a company can sell just one product each year into the end-customer market. There is no more market potential. In a normal environment, the company would record the sales for this one product every period. So far, so clear!

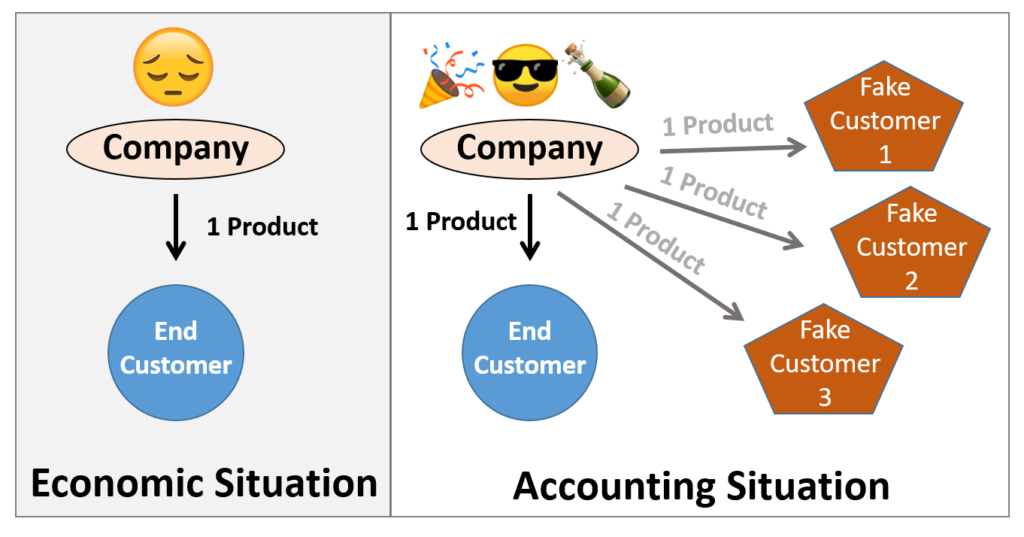

Now imagine that the company is looking for other “customers”, e.g. a reseller or distribution company. It is important that this distribution company is not related to the company (at least from the point of view of auditors) because otherwise a sale of products to this distributor would not exit the scope of consolidation of the company and hence would not show up as external revenues.

So now the company can already record two product sales in this period! But so far this only seems to be a slight gain of timing because the end-customer market will still be buying only one product in the next period and hence someone – the company or the distributor – has to suffer next period by not being able to sell its product into the market.

How to deal with this problem? In a next step the company takes out the oversupply by simply taking the distributor from the market: by way of M&A! The company simply acquires the distributor at the beginning of the second period. If we assume here that the distributor has nothing else than the one product from the last period on stock and no other activities, the acquisition price is just the price for the product.

Additionally, the company now sells one product (perhaps the one which is sitting in the distributor’s balance sheet because he could not sell it in the first period) to the end-customer. And it sells two products to two other distributors (or two to one other distributor). Now the sales count in the second period is already 3. This increasing revenues are generated at the cost of having to finance this weird transaction somehow – remember you need the cash for acquiring distributor 1. Usually the company has to issue fresh debt for this. Take care: Here one product is already sold twice – first to distributor 1, then reintegrated via M&A, and the sold to another distributor or the end-customer!

In the third period the company sells one product to the end customer and sells three more products to three other distribution companies (or one other distribution company, the structure here is just chosen for the sake of clarity). And of course it acquires the two distribution companies it sold products to in period 2. Sales count in this period: 4! Financed with debt. And so on. By the way, here are already two products sold twice (or one product sold thrice)! You see where it is going? It is simply a trade-off of increasing revenues by the cost of acquisitions. The company can generate market demand by buying back this demand later. Remember, this is still a market where there is only demand for one product per period by end-customers!

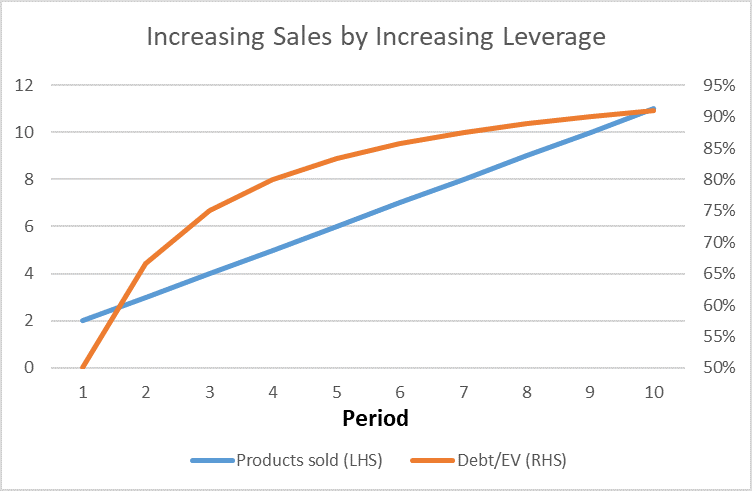

If we have a look at the balance sheet of the company, we can see that the leverage is growing over time. This is not a surprise. Effectively, the company has to take on new debt every period amounting to the additional revenues that it generates. If we start with a company that has two products on stock (50 Euros each) and a corresponding equity position of 100 Euros and we assume here for simplicity that it sells the products at a margin of zero (one to the end-customer, one to distributor 1), it needs fresh debt amounting to 50 Euros in the second period in order to produce a third product and sell it to distributor 2 or 3. This is how the debt / Enterprise Value relation develops over time:

It is a fantastic Ponzi-Scheme that is build up here. And the question is only: How long can the company do it. In order to perform this scheme within the rules of IFRS you particularly need two assumptions which are met in practice at a different degree of probability:

- The company needs several innocent enough, independent (!) distribution companies which perhaps do not oversee the real end-customer market potential.

- The company needs banks that are not able to not oversee the real end-customer market potential and hand out loans for the acquisition spree of the company.

From experience we can see that the first assumption is really a problem (sorry, a problem for the dishonest CFO, of course) in practice – in particular if companies want to play this game big. For bigger scopes of this scheme companies usually do not find independent distributors. But if companies do not play this game in such an exaggerated manner, if they only oversupply the market a bit, then the sometimes find at least some (or one) distribution companies. If not, then we are leaving he scope of GAAP. Then the field of accounting fraud begins. In this case companies “construct” the distributors themselves but pretend that they are independent – e.g. with no capital participation but perhaps with some interpersonal ties (where some employees of the company are founding the distribution company or similar). Fraud! But difficult to spot for some time if well hidden from the outside perspective and from auditors.

The second assumption is in most practical cases rather not a general problem but rather a problem of continuous application. If the company has some other activities and can back loans with these activities or if the company can even finance some of the M&A activities with equity or simply if the company uses its information advantage over banks to pretend a growing end-customer market: at least for a couple of periods companies might find financing for this technique. And this is often enough to greatly benefit from this scheme. So the example in the graph above with 10 periods of game playing is perhaps too much, but why not for 2,3 or 4 periods?

Just to make clear what this scheme means for other performance measures of the company:

- Earnings: This one is trickier to manipulate. In the example above we assumed for reasons of simplicity a zero-margin. This will not be the case in reality. But if you follow the logic of the example in more practical terms, the company will realise positive margins – at least for the sales to end-customers. However, the sales to the distributor will be neutral as long as these products do not go to the end-customers (which will eventually be the case for products that are sold several times). They will be neutral because the company reintegrates these products via M&A now at the higher value (already including the sell-in margin). But – no worries for dishonest CFOs – there are also ways of how to bring these margins up. One possibility is to depreciate product values in the course of the purchase price allocation following the acquisition (often done) with the difference now increasing the goodwill position. Another possibility is to increase the margins of sell-ins over time (this is rather possible if the company already controls the distributors beforehand). Or a mixture of both. Usually M&A accounting allows some discretion to management to also make the earnings benefit from this scheme.

- Cash flows: Net cash flows are not increasing here. How should they? Ok, admittedly, the will be impacted slightly by a bit of timing issues but not more. But due to the split of the transactions into an operating part (selling products) and an investing part (reintegration via M&A) the split into the partial cash flows will be impacted a lot. Operating cash flow will look good and growing while investing cash flow will be deeply negative. As long as investors see some positives in the M&A activity of the company – because they here falsely hope for future returns to these investments – they will not weigh negatively the negative investing cash flow as strong as they weigh the positives of the positive operating cash flow.

So, you don’t believe that companies play these games? Here are examples:

The most striking one is Valeant Pharmaceuticals International. The company – which meanwhile after a couple of accounting and business scandals renamed itself into Bausch Health – understood the functioning of the above revenue inflation technique very well. The company had a distribution company named Philidor which was originally set-up or at least supported by Valeant employees. As these employees knew that this interpersonal connection might be a bit problematic they didn’t use their real names but some more or less creative fake names such as “Peter Parker” (Spiderman) or “Brian Wilson” (the creative head of the “Beach Boys”). Before Valeant acquired Philidor (transaction clarity has come in December 2014 when they bought an option to acquire Philidor for zero USD) the company sold products to Philidor and recognised them as sales. After this date they (now rightly) consolidated Philidor and by this move reintegrated the revenues and were able to recognise them again. However, due to too many irregularities in the whole company setting, Valeant soon was in the middle of public accusations and investigations. These investigations also revealed their revenue double-counting trick. So Valeant eventually did not manage to set up a growing scheme of distribution company selling-and-reintegrating because they were caught before.

But as already mentioned, there is also the soft version of this game. In this case the distributor is independent at first and just doing normal business – and markets are usually not one-product markets – and gets caught by the acquisition by surprise (or at least without any long-term plan in place). In these cases companies benefit in revenue-terms from acquisitions of distributors mostly “en passant”. This means there are clear business logics to buy the distributor to which the companies have sold products beforehand – e.g. in order to establish a local distribution hub in a foreign country – but companies also benefit from the reintegration-based sales boost. It is important to note that there were no accounting-relevant relations before the transactions, so here everything takes place within the allowed scope of GAAP – and without any bad intentions.

Spectris Plc., a producer of specialised measurement instruments and controls, did it a couple of times e.g. in Taiwan, South-Korea, Japan and China. Brazilian Foods SA bought one of its suppliers (2,500 employees) in the United Arab Emirates in 2015. In 2017, Japan Tobacco just integrated a whole value-chain by buying a producer PT Karyandibya Mahardhika and its distributor, PT Surya Mustika Nusantara in Indonesia in one go. In 2016, NuVasive Inc, a US-based medical devices company, bought one of its distributor in Brazil, and so on. These are just a couple of examples. And again, as far as we know they did these transactions for good economic reasons – but they also somehow benefited in terms of the revenue effect: en passant. And of course there are also some suspect-companies out there which don’t do it with good intentions (at least this is what I think) but I cannot uncover them here because their proceeding is still ongoing.

For analysts this customer-as-a-partner variant is a tricky situation as in most cases a clear adjustment of sales is not possible. But a rough adjustment is always better than none. In particular, analysts should look at the following points:

- Always be ready for revenue (and cash flow and – perhaps – earnings) adjustments if a company buys a distributor or reseller

- Try to find out what the sales to the distributor are before the transactions. Take into account the shelf-life of the inventories. In food it is rather low, in some industrial products it can be high (the high shelf-life products are more probable to be sold twice)

- Try to find out what the margins of a) sales to the distributor and b) sales to the end-customer are. Make adjustments to your forecasts.

- Check the notes regarding the purchase price allocation after the acquisition. Are there any value adjustments to inventory (a depreciation would allow to not only increase sales but also to stabilize or even increase the margins of these future sales)