Belgian football is one of the most attractive in the world, even though the national first league is not so much loaded with international top stars as e.g. the Spanish or the English league. The country has brought out all-time top stars such as Jan Ceulemans, Enzo Scifo or Eden Hazard (to name but a few). And so it goes without saying that it is quite attractive for broadcasting entities to have the ability to show the games of the Belgian Division 1A (‘Jupiler Pro League’) to their customers. For the current season, the broadcasting rights owner Eleven Sports Belgium has entered into several distribution agreements for its three new football channels with companies such as Telenet, Orange Belgium, Proximus, VOO, Télésat/TV-Vlaanderen etc. For our today’s blog post, it is particular the two OTT (over-the-top, i.e. transmission of content via internet) players Orange Belgium and Proximus as well as the cable-TV provider Telenet (corresponding to their initial letters, the companies are called OPT-companies in the text below) that we are interested in.

With the Q3/2020 numbers two of these OPT-companies – Telenet and Orange Belgium – have shown the licence agreement with Eleven as ongoing expenses directly flowing through the P&L, while one company – Proximus – has capitalized the licence agreement as an intangible assets and recognises expenses only indirectly via amortisations through the P&L (as far as we understand, all three companies have the same contracts). This raised a lot of discussions among investors on whether such licences give rise to an intangible asset according to IFRS or not! Or putting it differently: Who is correct with the accounting treatment: Telenet and Orange Belgium on the one hand side? Or Proximus on the other hand side?

The question about how to deal with such licence agreements from an accounting point of view usually brings us directly to IAS 38 Intangible Assets. However, if IAS 38 is not relevant we might also check IFRS 16 Leases. In the definition of the scope of IFRS 16 it is explained that “rights held by a lessee under licensing agreements within the scope of IAS 38 Intangible Assets” are excluded from IFRS 16 (IFRS 16.3 e). This means by implication that if these licence agreements are not assets according IAS 38 (and only then) they might still be assets according to IFRS 16. And finally we should not forget to check IAS 2 Inventories.

We start with IAS 2. Although it makes little difference in practice to an IAS 38 asset – neither in terms of valuation at first recognition nor at subsequent amortisation – we have seen in the past some broadcasters that have classified broadcasting rights as part of their inventories. However, we think that broadcasting rights or licences do not really qualify as inventories. The right or the licence is a means of distributing content but the right or the licence is not the asset per se that is sold, and hence such rights and licences are not covered by the basic asset definition of IAS 2.6 a: “…held for sale in the ordinary course of business”. Therefore, we think it is not necessary here to go deeper into IAS 2.

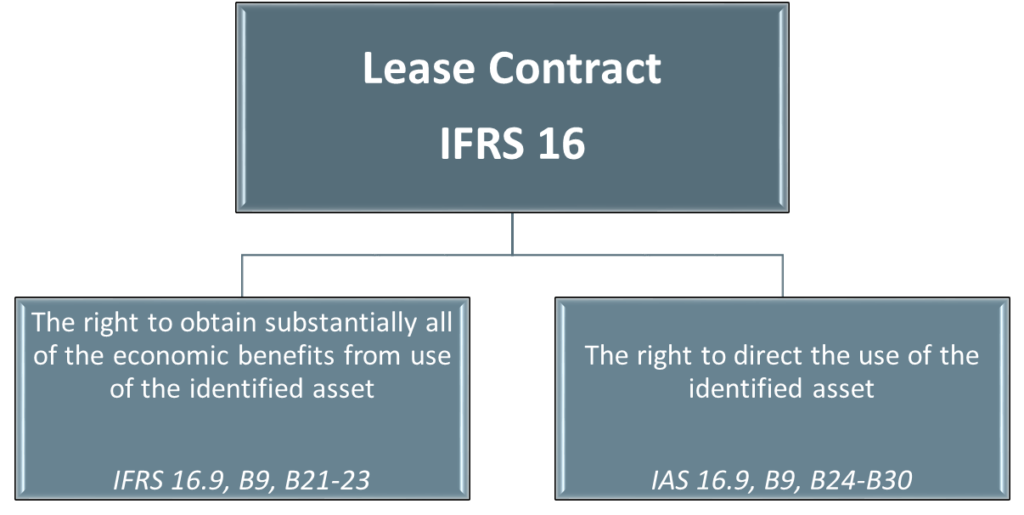

For didactical reasons we then first check IFRS 16. The following graph highlights the criteria of whether a contract can qualify for a lease asset.

At this point it is necessary to first look at the agreement of the OPT-companies with Eleven Sports in a bit more depth. In fact, the agreements do not grant a broadcasting right but they are rather some sort of selling or distribution licence of the broadcasting right. So it is rather some sort of a right to sell the original right. This is important when checking the criteria of IFRS 16 (and also later IAS 38).

With regard to the first criterion above (right to take economic benefits) things are more or less clear. The OPT entities are paid for customers using the licence, usually via different sorts of data- or other contracts. However, with regard of the ‘right to direct the use’ things are not that clear at first glance.

Here it is important to differentiate between the original broadcasting right or the distribution licence. With regard to the original broadcasting rights the three OPT-companies certainly have no right to use. These rights are lying at Eleven Sports. With regard to the (non-exclusive) distribution licence we have to look deeper into the standard.

In IFRS 16 B24-B30 we find very detailed criteria what the ‘right to direct the use’ of a lease asset means. Some of these criteria might be fulfilled by the licence agreement but some of them are rather not fulfilled. E.g., IFRS 16 B24 b)i) says that entities should have the “right to operate or to direct others to operate the asset, without the supplier having the right to change those operating instructions”. We doubt that the OTT-companies have these rights. In particular they are not able to sub-licence. Furthermore, IFRS 16 B 26 a) states that entities should have the “rights to change the type of output that is produced by the asset”. It is also rather unlikely that OPT-companies have this discretion about how to use the licence. Hence, we do not think that the IFRS 16 criteria for asset recognition are fulfilled here.

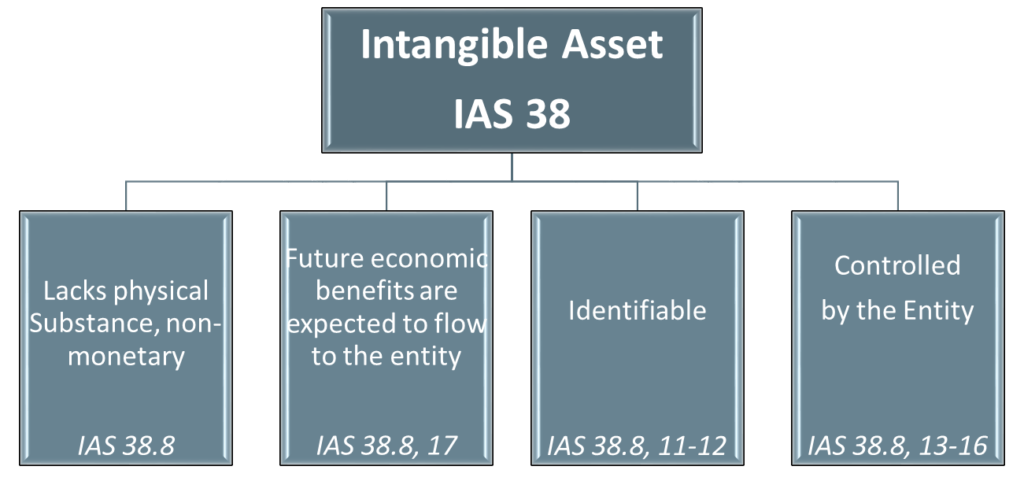

Finally, we have to check IAS 38 Intangible Assets. The criteria for asset recognition are listed in the below graph.

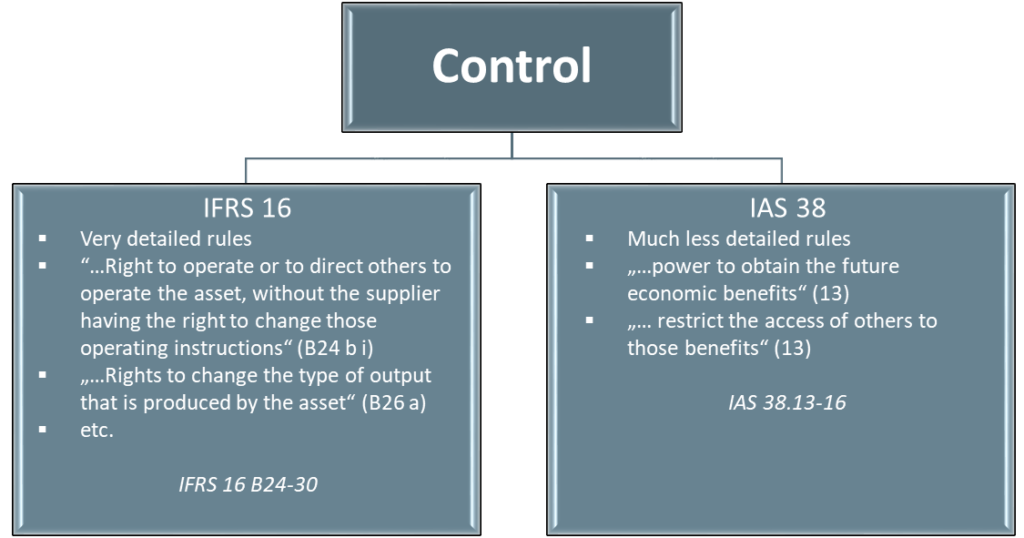

Here we can also check very quickly the first three criteria for the distribution licence. However, the IAS 38 ‘control’ criterion is not so clear. It also seems as if this criterion is very similar to the ‘right to direct the use’ criterion of IFRS 16. So let’s have a look at how IAS 38 defines control.

In IAS 28.13-16 we can read about the control definition. It is evident that the criteria written here are much softer than in IFRS 16. In particular, the standard states in IAS 38.13 that control requires a) the power to obtain the future economic benefits and b) the ability to restrict the access of others to those benefits.

As customers have to pay (directly or indirectly) for watching the football content, the OPT companies have the power to obtain the future economic benefits – each OPT company separately within its licence. And as each OPT-company also has the ability to exclude from the use of their licence those viewers that do not want to pay or that have no contract with the specific OPT-company, OPT-companies also have the ability to restrict the access of others to those benefits. The OPT companies even have legal claims for this. So we can conclude here that at our opinion the criteria for recognition of an intangible asset according to IAS 38 are met!

The relevant analytical step for this conclusion is here to differentiate between the criteria for control of IFRS 16 and IAS 38, see in the summary graph below.

Four points are still worth mentioning here:

- Some argue that due to the non-exclusivity of the licences it cannot be possible for each single OPT-company to restrict others from seeing the football content (customers can simply sign for a contract with another OPT-company or with Télésat/TV-Vlaanderen of VOO), and hence the control criterion of IAS 38 is not met. This is, however, only true as long as we talk about the original broadcasting rights. If we talk about the single licences then OPT-companies can restrict others from using this licence. And it is the licences which are the assets here.

- Other arguments relate to the problem that by splitting the original broadcasting rights into several sub-licences (as seen from the viewpoint of Eleven Sports) there would be a magic multiplication of intangible values without any economic justification for it. That is why these licences should not be seen as IAS 38 assets. However, only because there are several (non-exclusive) sub-licences there is no creation of value-out-of-nowhere. Of course, the single licence-partners know that there is no exclusivity and they will pay for the licence accordingly, i.e. certainly much less than for an exclusive licence.

- Some observers pointed to the ‘IASB Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting 2018’. In paragraph 4.20 it is stated: “An entity controls an economic resource if it has the present ability to direct the use of the economic resource and obtain the economic benefits that may flow from it. Control includes the present ability to prevent other parties from directing the use of the economic resource and from obtaining the economic benefits that may flow from it. It follows that, if one party controls an economic resource, no other party controls that resource.” So according to these observers, this general rule – which is very similar to the IFRS 16 wording – should be also applied when looking at IAS 38 and hence there is no difference in the control-concepts of the two standards which means that the licences are no IAS 38 assets. However, in practical application the Conceptual Framework only has subsidiary character. This has been made clear by the IASB itself: “The staff have performed an analysis and have concluded that if an IFRS Standard specifically applies to a transaction, other event or condition, an entity applies the requirements of that Standard, even if those requirements conflict with concepts in the Conceptual Framework.” (Source, Deloitte report of the May 2018 IFRS Interpretations Committee meeting, HERE). Hence, the wording of IAS 38 is still the relevant one here.

- From a pure analytical point of view, things are manageable. If an analyst thinks that the licences are assets in an accounting sense she has to adjust the financial statements of Orange Belgium and Telenet. If she thinks the licences are not then she has to adjust the financial statements of Proximus for analytical purposes. Don’t forget that such adjustments also touch the aspect of whether the payments for these licences to Eleven Sports are to be seen as part of the operating cash-flow (no-asset case) or the investing cash-flow (yes-asset case). However, such analytical exercises are (at least roughly) manageable with the available set of information. We do not follow the assessment of one big brokerage house in recent weeks which commented that they are cautious regarding Proximus simply because of its accounting treatment of these licences. Again, if one is not happy with the accounting treatment one can easily adjust it. This is even more true as our analysis has shown here that between capitalizing and not-capitalizing is very fine line.

- All these analyses are performed based on our understanding of the licence contracts. They might look differently in reality (which we do not know) and this might also change the assessment regarding the accounting treatment of these licences. However, we also want to emphasize that it would be a very special case if these licences would not allow OPT-companies to “to restrict the access of others” to these licences (the core criterion here).

And as a bonus here for all of you who managed to read through till the end: A picture of the famous “Wrong Socks” game of the Belgium national team at the Football World Cup 1954. Watch the colour combination of the socks, compare it to the correct colour combination at the wristband, and see how Huysmans and van den Bosch (the players at the very right hand side) deal with this issue.

17 June 1954, Basel, Stade Saint-Jacque, England-Belgium 4:4, from left to right: Mermans, Anoul, Carré, Dries, Mees, Gernaey, Houf, Coppens, Van Brandt, Huysmans, van den Bosch

Disclaimer:

We hold no economic stake in the companies mentioned or involved in this blog post – in whatsoever direction. We base our analysis on imperfect information and hence we might be wrong with some conclusions. This is just our subjective view and no investment recommendation at all.

Appendix:

Here you can see how Proximus reports about its accounting treatment. Obviously, the company does not feel super-sure about its proceeding. We understand this and welcome the quite cautious wording of Proximus.

Source: Proximus Q3/2020-Report, p. 11.

Source: Proximus Q3/2020-Report, p. 26.