The IASB and the FASB have one important red line when it comes to intangibles accounting: With a couple of clearly defined exceptions (e.g. for IFRS following the criteria of IAS 38.45) it is NOT possible to recognise own developed intangibles as an asset! And this makes absolute sense – too big would be the degree of management discretion and leeway to initially and continuously value these economic assets. It would open the door for basically any asset recognition, and this would not be in line with the need for reliability of numbers.

Companies can, however, bring most of the intangibles onto the balance sheet if they buy them – also if it is as part of a company acquisition. In this latter case the purchase price allocation (PPA) allows for seeing customer relationships, brands and trademarks, etc. and of course: goodwill of the acquired target on the asset side of the buyer’s balance sheet. Obviously, the quantification problem at initial recognition is much smaller (though still existing due to distribution issues) if companies have paid a consideration for these assets in the first place.

I think the intentions of standard setters are quite clear. However, companies are not always super interested in standard setters’ intentions. In fact, for companies it would be very attractive to bring some more intangibles onto the balance sheet as it is the attractive shareholders’ equity which stands at the liability side against them. And as we know, often CFOs’ creativity is unlimited when it comes to moving the limits of accounting, so it would be very astonishing if they do not find a way…. and of course they do!

There is even a name for this accounting technique: BIOLSI – which is short for ‘Buy Intangible! Overstate Life! Stuff Intangible!’ We are going to explain below how it works. But for better understanding we have to start with some accounting basics first:

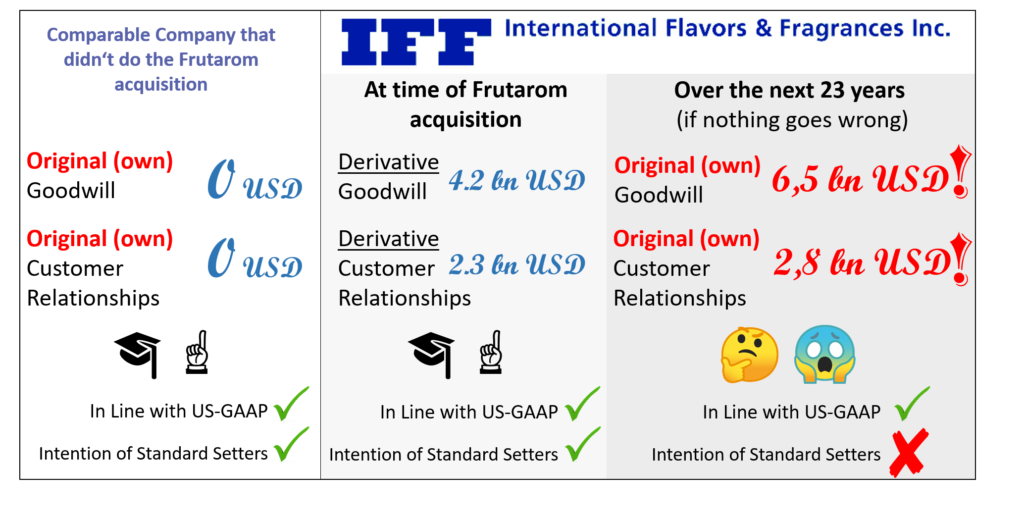

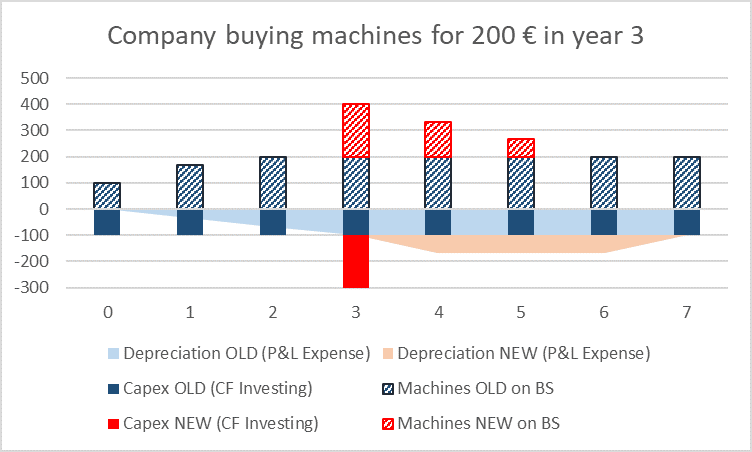

Imagine a company that produces some goods with the use of machines. Each machine has a useful life of let’s say 3 years. If the company wants to go concern, it has to replace the machines at the end of the useful life of each machine in order to continue with production at the same level (no growth assumed here). So this is how the relevant numbers of this company look like for running a total of 3 machines in the steady state and each machine costing 100 Euros. Due to ramping up our model, the steady state is not reached before the end of year 2.

In the steady state there is one machine at 100 Euros (freshly bought), one machine at 66.67 Euros (one year old) and one machine at 33.33 Euros (two years old) – together 200 Euros book value. Each time an old machine exits the machine park, a new one is bought. So the total book value of machines stays constant over time. Depreciation starts in the year after the acquisition which is why the steady state for depreciation (3 times 33.33 Euros = 100 Euros) is reached in year 3.

Now let’s assume that the company additionally makes a one-time acquisition of two machines at the end of the year three. The numbers now look as follows.

This transaction leads to additional (investing) cash outflows, additional assets and additional depreciation over time.

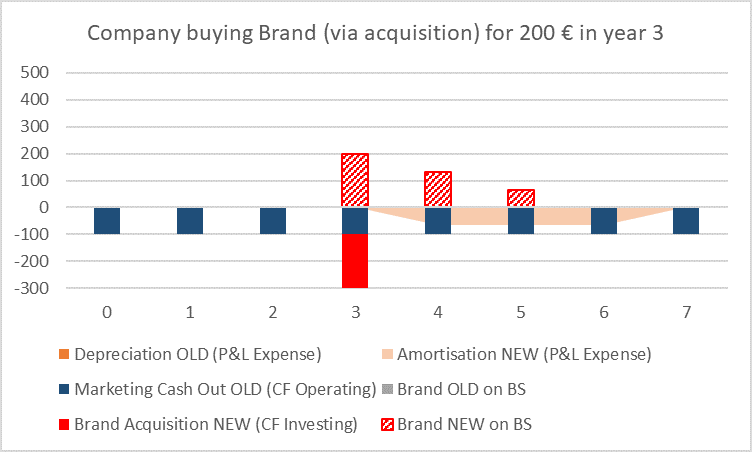

Now let’s switch to a slightly different business model. Imagine that another company provides some consulting services (no assets on the balance sheet so far) and invests a lot in marketing. In period three it acquires another consulting firm for 200 Euros. The PPA indicates that the whole 200 Euros are paid for the brand of this company. It is further assumed that this acquired brand value has a useful life of three years and is amortised following a straight-line method. Here the numbers look as follows.

Just as a remark: Letting the practical problems of useful life determination aside, setting a limited useful life for intangibles makes a lot of sense from an economic point of view. Intangibles such as brands, customer relationships simply have a limited economic useful life per se. If companies do not reinvest (marketing, customer acquisition and maintenance programs, etc.) to keep the asset base more or less constant, the value of the assets will fade. In reality, companies such as e.g. Coca-Cola really do a lot to keep the value of its brand at level.

Nevertheless, we can see that the graph above looks a lot like the case of the company that buys machines for 200 Euros in year 3 – which should not come as a surprise. From an economic point of view the two cases are not too different. Here, however, it is not machines but the derivative brand value from the transaction that it is about. What happens here is all within the rules of IFRS and US-GAAP and in line with standard setters intentions.

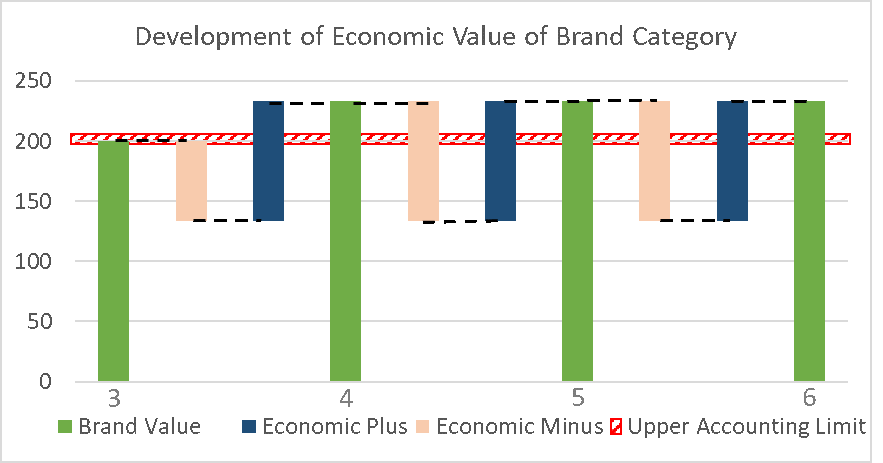

However, in reality we see it quite often that companies do not want to commit to such short asset lives. They rather set a longer life or – even better – a so called “indefinite” life. It is important to note that “indefinite” does not mean infinite. It only means that the asset is checked for impairment (or indications thereof) in regular intervals. The argument is here that IF the brand asset life is in fact only 3 years THEN we would have a similar book value path as in the graph above as the loss in fair value would be recognised every period. So nothing should change if companies use an indefinite asset life or a three year life…

But stop! This is not the case. And we do not talk about the discretion that management has when performing impairment tests – we only talk about the hard rules of US-GAAP and IFRS. The problem with the above line of arguments is that our accounting standards cannot isolate intangibles down to the smallest unit. Brand is the total brand that relates to a certain part of the organisation (and not split down to the viewpoint of single stakeholders), customer relationships are the total customer relationships of a certain part of the organisation (and only rarely split down to specific customers), etc. And the standards also do not differentiate with respect to the time of original build-up of the intangible (not like in the case of machines where we clearly see when each of them has been bought). In short: The standards see the single intangibles mainly as umbrella categories!

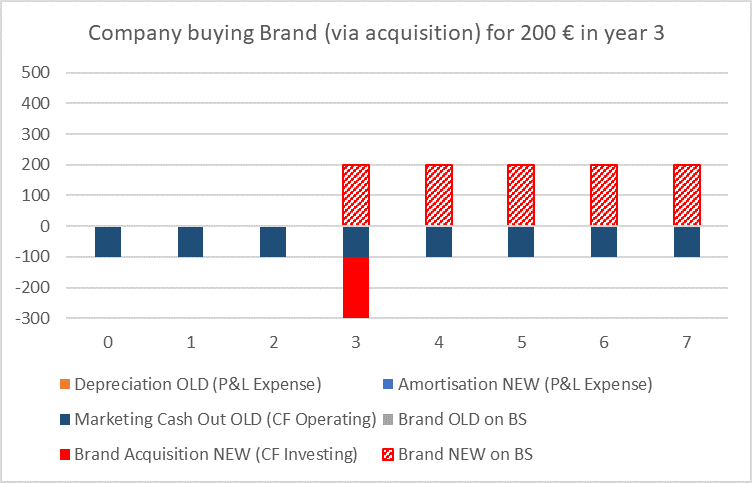

While this might be understandable from a practical point of view, it has a highly negative side-effect: Due to this umbrella categorisation periodical pay-outs/expenses (e.g. for marketing) that generate new intangibles from an economic point of view (but not from an accounting point of view) are simply thrown into the big category-pot – and are considered in the revaluation of the intangible. These pay-outs work the same way as fresh investments in these intangibles. In the case of the brand that was bought in year 3 in our example above, the assumption of an indefinite life would lead to the following situation.

The brand would lose in value (economic minus) according to the economic three year useful life (-66,67 Euros in year 4) but would get support from the 100 Euro marketing pay-out (this is the economic plus). This leads to a value of 233.33 Euros. If it is now checked for impairment one would see no reasons for write-downs. As the upper accounting limit is 200 Euros, the accounting value of the brand would not change in year 4. Similar in year 5: now the amortisation is higher (because of the higher brand value) but still the fair value of the brand would not drop below 200. And so on. Our general example would look as follows.

Now it is not only the assets which are higher in the future. It is also the amortisation charge which is missing totally in the numbers now. This obviously leads to higher earnings (a.o.t.b.e) as compared to the example before.

It is highly important to note that this development is due to the umbrella categorisation of intangibles which allow periodic investments to be recognised as value drivers for already recognised intangibles. And this finally means: Companies can build-up own (original) intangibles by means of their periodic cash-outs that follow the initial recognition of the intangibles. This is in line with the standards – but I guess not in line with the intentions of the standard setters.

By the way, what works for intangibles in general, certainly also works for goodwill in particular. And if you now want to know how companies can best benefit (?!) from this accounting loophole we come back to the already mentioned BIOLSI-technique.

Some companies play this BIOLSI game very aggressively. For example, the European beverage sector (ABInbev, Pernod Ricard, etc.) has always delivered great examples of ultra-long intangible asset lifetimes following acquisitions. Not only the goodwill positions (which by definition of the impairment-only approach have an indefinite life) but also the accounting brand lives were often set “indefinite”. A nice current example – although not a European beverage company – is New York-based specialty chemical company International Flavours & Fragrances (IFF).

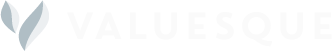

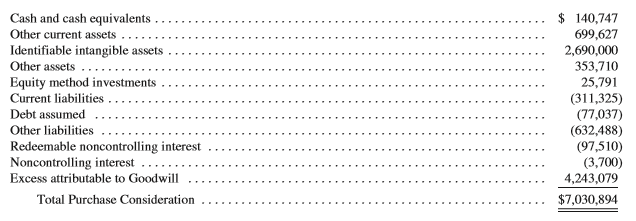

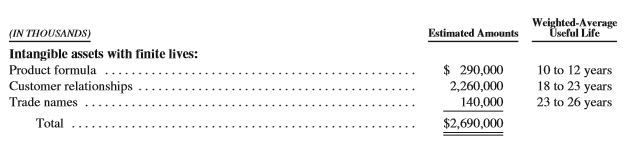

On 4 October 2018 IFF completed the (transformative) acquisition of Frutarom Industries Ltd. In the following purchase price allocation process (PPA) the company managed to isolate a lot of intangibles (Step 1: Buy Intangible! “BI”). Moreover, IFF also managed to recognise a huge part (ca. 60%) of the consideration as goodwill (indefinite life) and to assign very long useful lives of on average roughly 20 years to the non-goodwill intangible assets (Step 2: Overstate Life! “OL”).

Remark: IFF also made somehow clear that they would rather have indefinite useful lives for the non-goodwill intangible assets. We can read this from the reaction of management to exclude basically all intangibles amortizations from their non-GAAP performance measures. However, obviously here the auditors didn’t want to go the way of indefinite life assumptions for e.g. customer relationships, but instead agreed to a (rather weak) compromise – but this does not make things much better from an economic point of view!

Finally, IFF has to invest further in these intangibles in order to keep them alive (or better: in order to allow for a lot of own goodwill and own intangible recognition in the future) – Step 3: Stuff Intangible! ‘SI’! Looking at the 2018 accounts, IFF has roughly 700 mio USD SG&A expenses (this is the position where most reinvestments in intangibles are hidden). As we will see, this should be enough for benefiting maximally from the BIOLSI-technique (if not something unexpected happens in the next years).

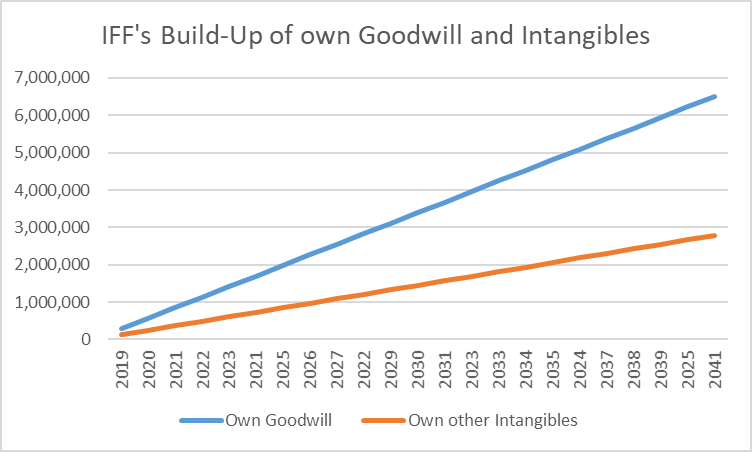

Now our analysis: Given this information we first assigned useful lives that are more economically sound to the single assets that IFF acquired (before reinvestments): 15 years for goodwill and 10 years for the non-goodwill intangibles (which are admittedly still quite high numbers). This allows us to find out how much IFF will implicitly (and hidden from the eyes of investors) recognise as assets now on trade names, customer relationships and goodwill over the coming years: it is the difference between the goodwill respectively the carrying value of the other intangibles on the one hand side and the economic value on the other hand side. This is roughly 400 mio USD per year! Against the background of the ca. 700 mio USD SG&A expenses already mentioned above we think these 400 mio USD reinvestments in intangibles can be delivered in order not to trigger an impairment in a normal business environment, even if we assume that a lot of these 700 mio USD accounting expenses will be real periodic expenses. This is even more true as a) it is not only SG&A which reinvests in these intangibles but also other pay-outs – in particularly if it is about backing the goodwill position – and b) as we assume that SG&A will rise anyway in the coming years in the combined company.

Altogether, as long as the general environment does not deteriorate (which might trigger impairments), IFF should be able to bring roughly 6.5 bn USD of OWN original goodwill and 2.8 bn USD of OWN intangibles over the coming 23 years by way of the BIOLSI-technique onto the balance sheet!

So what? Is it bad what IFF does? This is not very easy to answer. First, many companies do it like IFF although IFF is one of the most aggressive ones currently. Second, in particular for goodwill it is not the company who is doing something wrong it is the standards that force this build-up of own goodwill by the mandatory impairment-only approach (which means that there is no way out of the indefinite life assumption for goodwill). Third, from an economic point there is nothing wrong with bringing economic assets onto the balance sheet. But fourth, the big problem is that IFF is doing something that a company which does not grow by acquisitions cannot do. This clearly weakens the comparability to other companies and obscures a lot of what they do.

As a summary, analysts should be aware that our accounting standards often allow more than the standard setters originally intended. In the case of the goodwill impairment-only topic or the BIOLSI technique, however, it is possible without too many assumptions to adjust the numbers to a more economic setting (and to generate a higher degree of comparability with other – non-acquisitive companies).