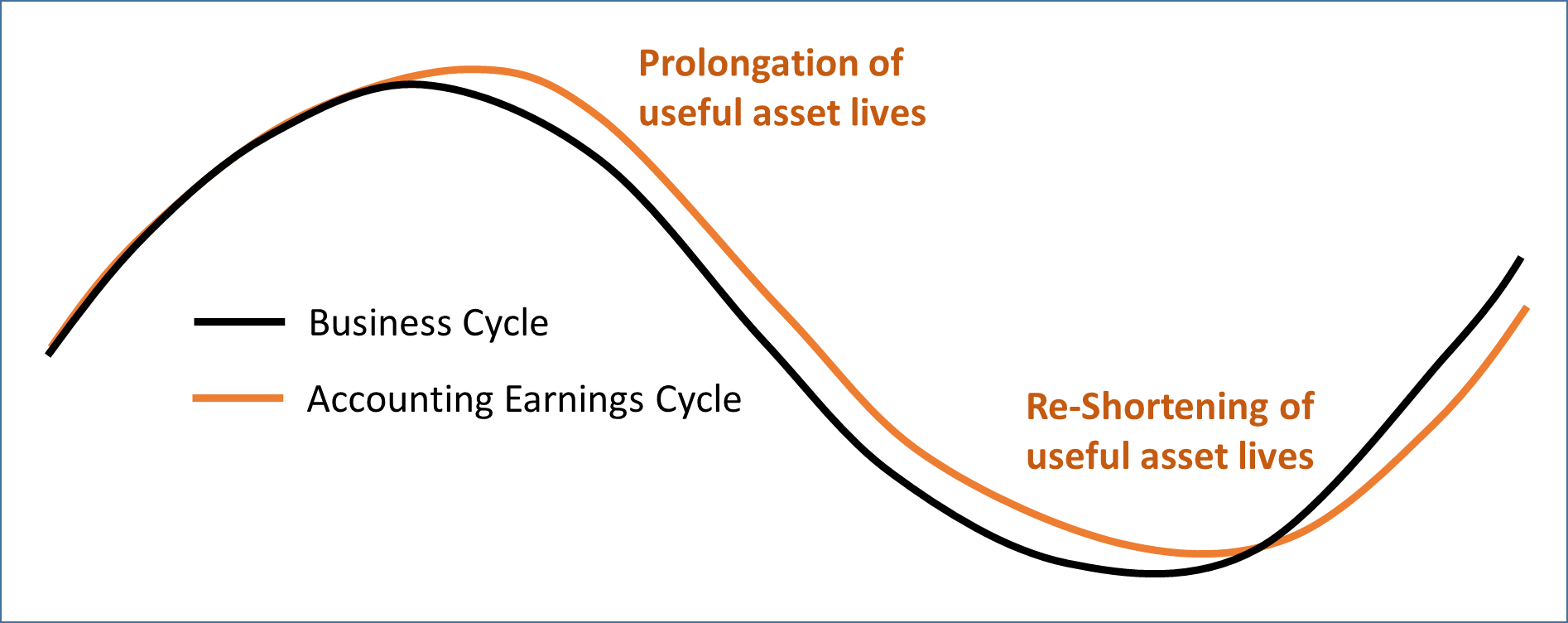

There is an old rule of thumb in financial analysis: The end of the cycle is near when companies start to increase the accounting useful lives of their assets! And this is in fact observable in quite a lot of cases – on a macro scale (for the whole economy) as well as on a micro scale (for single companies). But why should this useful-life-prolongation be such a good indicator for a down-swing? Five reasons for this:

First, it works as an earnings push-up! All other things being equal, increasing the useful life of assets means that the annual depreciation charge decreases (the depreciable value is now split over an increasing number of years). And this leads to increasing earnings (EBIT and Net Income).

Second, useful life adjustments can be played as an accounting-only game. If there is no support from the business environment anymore, companies can still kick their earnings once again. Third, it is not an exotic topic. Every company has at least some depreciable assets.

Fourth, in many cases (though not in every case) it is extremely difficult for e.g. auditors to spot whether useful life assumptions are conservative, reasonable or aggressive. Don’t forget, we are often rather talking about decades than about years. Who would think himself to be able to clearly falsificate companies’ assumptions here? Even for companies with basically the same business model and almost commodity-like assets, CFOs can get away with totally different life-assumptions for their assets, as e.g. UBS-analyst Cristian Nedelcu highlighted in a very interesting recent study on aircraft accounting practices of European tour operators („A closer look at tour operators’ accounting“).

And finally: Fifth, when managers get proven wrong they often have long left the company or are even retired – thanks to the not seldomly quite long asset lives that are in play here. So, not a big risk to be found guilty as a window-dresser.

Of course, not every extension of accounting asset lives is a cheat. There might be good reasons for it (e.g. new evidence), the same way as there might be good reasons to shorten asset lives. But sometimes there are no good economic (or technical) reasons and then it is important for valuation experts to spot it and to draw the right analytical conclusions. The good news for equity investors: there is a fair chance that CFOs get caught by analysts in this cycle more often than in the past. Because this time things are different (and I know how careful capital market participants must be with this phrase).

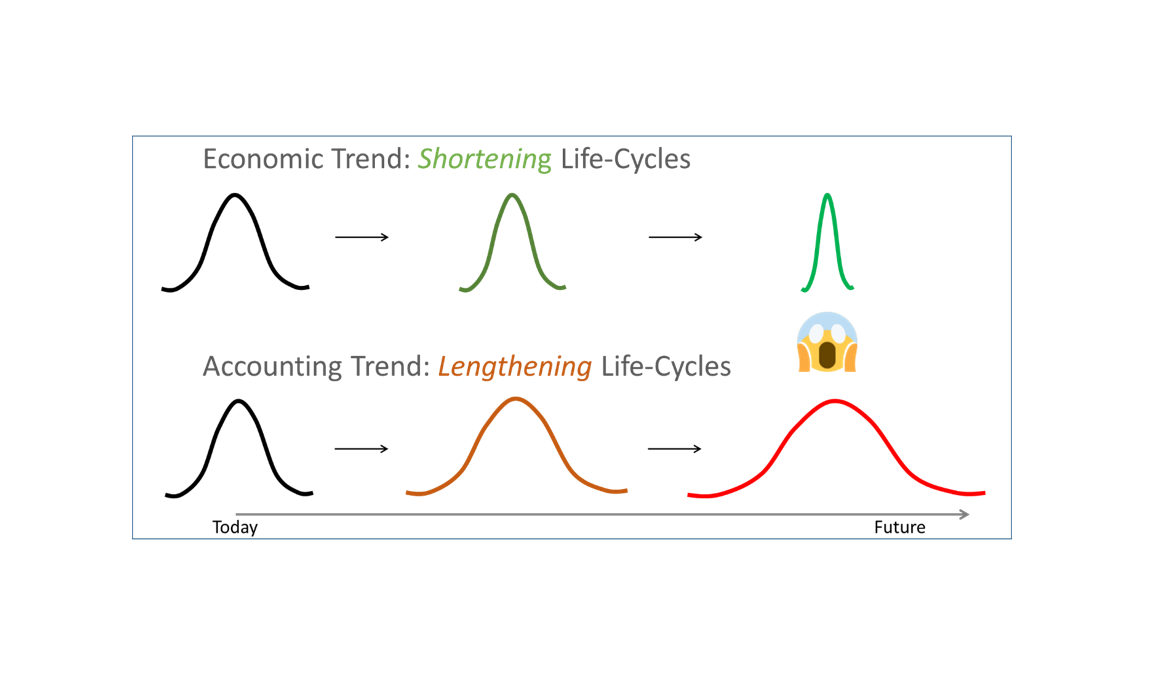

Things are different because since a couple of years we see a clear tendency towards shorter economic life cycles accross all sectors: product life cycles, busines life cycles and also useful-asset-life cycles. It is mainly the big mega-trends such as digitalisation, AI, climate change or new customer behavior that lead to this already observable but even more so future-expected trend. There are companies being reluctant to build new production facilities because they do not know whether this sort of facility will still be „useful“ (Sic!) in a couple of years when new digital solutions are available. We see oil companies struggling to understand how much of their reserves are already „stranded assets“ because they might not be burned in the future anymore. And we see more and more customers who want to keep their flexibility over time and therefore prefer to enter into subscription contracts rather than buying assets – just to be able to switch in and out or change it whenever they want, and thereby putting additional pressure on the useful lives of assets. All these trends (or at least the fear thereof) are certainly also one important – though not the only – reason for the general capital expenditure weakness we could observe in our economies in recent years.

If now these real economic asset-life-decreasing effects meet the accounting asset-life-increasing effect we can sometimes observe quite interesting things. And we do not even have to look far back. On 25 February 2019, the South Africa headquartered international fossil-fuel-to-liquid conversion company Sasol announced that it is extending the useful life-end of parts of its Sasolburg plant from 2034 to 2050. It was just in 2014 that Sasol has also prolonged the asset lifespan of its Secunda plant to 2050. In this context it is important to note that Sasol is – led by these two plants – currently the biggest CO2 emitter listed in South Africa, with higher p.a. emissions than whole Portugal. And South Africa – though still dependent on its coal – is not at all a climate hostile country. Against this background it is – to say the least – very hard to believe that a sound forecast on useful asset lives of super-CO2-emitters for the next 30 years is possible. And if something is to change, it is probably not an increase but rather a decrease. And if it really must be an increase, it is certainly not a doubling of remaining asset lives that a prudent, climate-discussion aware CEO, who has no accounting motivations, would set today.

This prolongation move of the Sasol management looks even more dubious when taking into consideration that it was just in November 2018 that Sasol management got heavily under fire from all sides at the Annual General Meeting because of their huge CO2 emissions, and that the sustainable development scenario of the International Energy Agency (IEA) does not at all foresee a long coal-burning future of the Secunda plant. But none of this convinced the auditors, and the company reached its goal: a noticeable reduction of its annual depreciation charges.

Not of the same quality but at least the same direction is power equipment provider Aggreko’s recent move to increase asset lives of their transfomers resp. switchgears (equipment that sees constant technological development, driven also by carbon footprint reduction trends) by 50%, thereby pushing pre-tax earnings up by 5%.

The fashion online retailer Asos does not explicitly disclose changes in useful life assumptions, but a fundamental analysis (roughly: average useful life equals gross assets devided by depreciation/amortisation) suggests that the company has strongly increased the average useful life of both its software assets and ist physical assets over the years. Not a really intuitive move for a company in such a fast changing business environment but perhaps triggered by the weakening cash flow profile over the years.

These examples already highlight: It will get trickier for companies in this current business environment to play the useful-life-game without being spoted. This, however, does not mean that still some companies will sell this story successfully to the markets. And of course, in several cases it will be absolutely appropriate from an economic or technical perspective to adjust the life a bit downward or upward. Nevertheless: For analysts and equity investors it is important to keep the drivers of generally shortening economic life cycles in mind when checking such corporate moves for plausibility.

Two final remarks on this topic:

First, even super-fundamental analysts and DCF-supporters cannot claim here that depreciation is a non-cash charge (see here for a short analysis of the cash/non-cash nature of write-downs[in German]) and that it doesn’t matter at all whether it is high or low. They cannot claim this because useful life assumptions also set the timing for replacement capex forecasts and hence will directly feed through to future cash flow assumptions (if analysts believe in them).

Second, it is by the way interesting to see that some companies are preparing this end-of-cycle adrenaline-rush to their results for a very long time (by reducing asset lives beforehand and building up reserves) – or at least that they look for a good timing to perform inevitable decreases of asset lives. E.g., the Canadian media company Corus Entertainment waited until the operating ad-business showed clear signs of stabilisation end of 2018 until it finally performed the long expected reduction of the useful life of tv brands from eternal down to 3-20 years.