This problem can really bring a dishonest manager’s decision making process to a breaking point: Overstating revenues (and hence earnings) is one thing, but if you want to draw a complete and consistent picture of this fraudulent behaviour you have to declare the overstated earnings to the tax authorities and consequently pay income taxes for them. However, this would mean that a company acutally has to spend a lot of lost money (cash) for establishing the imagination of a better business – and this again often raises the question whether it is necessary to deliver the full (and expensive) set of hokuspokus or whether the cheap version also suffices.

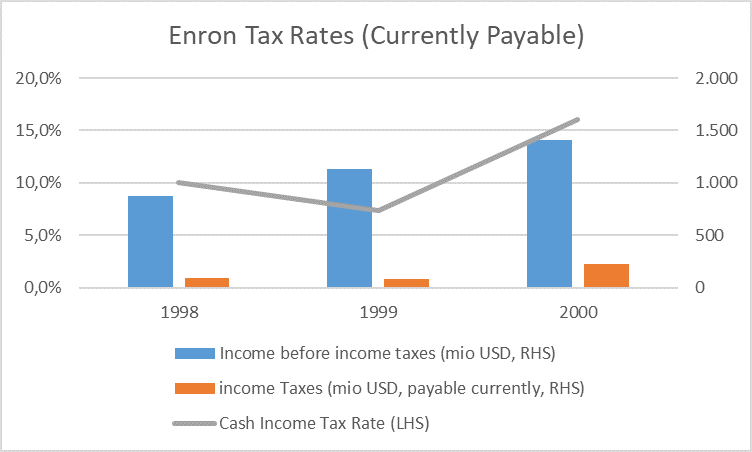

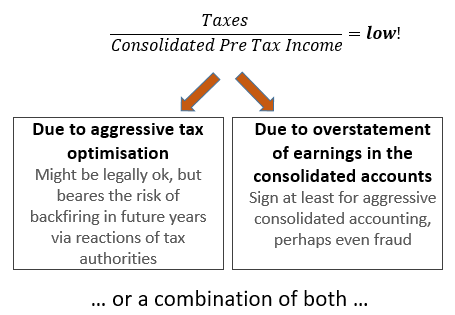

The management of Enron had a clear opinion on this: Tax authorities and investors are different sets of adressees, and tax accounting and US-GAAP are also different (at least to a certain degree). So why not also dealing differently with these two worlds? As a consequence, Enron decided for the cheap version: Management artificially inflated earnings in Enron’s consolidated accounts but told more or less the truth in the tax accounts. The interesting thing about this proceeding is – and now we get to the point – that it creates a nice little mismatch in the consolidated accounts: The tax rate, i.e. the taxes paid in relation to the consolidated pre-tax income, will be very small and very far away from the average statutory tax rate. In fact, with hindisght we know today that the low cash tax rates of Enron have been one of the rare warning signs that investors could have spotted before the full fraud was uncovered in 2001.

But just showing a low cash tax rate is not necessarily a warning sign for earnings overstatement per se. It could well be that it is not the consolidated part of accounting where the company is aggressive, it could also be that it is the tax accounting where optimisation is sought. Big internet companies have played this game very well in recent years. By using the flexibility and transitoriness of their business activities as well as the lack of international tax coordination they often end up with extremely low actual tax payments. Take Amazon.com Inc. as an example. In 2017 and 2018 the company managed to not paying federal taxes at all in the US (even getting reimbursements). As a consequence, at the very low point in recent years (in 2018) it showed an effective income tax rate of only 11%.

In the case of Amazon, the tax evasion possibilities are relatively well-known (but quantification is still a big problem). If such evasion opportunities are not known to investors, then a view on some comparable companies would help to find out that a lot of these internet companies are aggressively optimising tax payments – and such a broad phenomenon is also rather a sign of tax optimisation than of overstatement of consolidated earnings.

In the case of Enron, however, there were not such obvious tax reduction possibilities, and similar companies had much higher tax rates then Enron. What we have here are two cases – Enron and Amazon – with similar tax rates in the consolidated statements but with totally different economic explanations for it. Hence, this comparison shows how important it is for investors to understand at least the basics of tax determination in countries of operation and of the business model as a whole – although we admit that this is not at all an easy task when e.g. analysing a globally operating company with a huge number of different tax regimes that it touches.

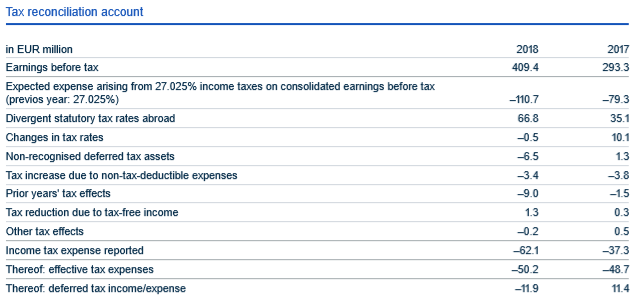

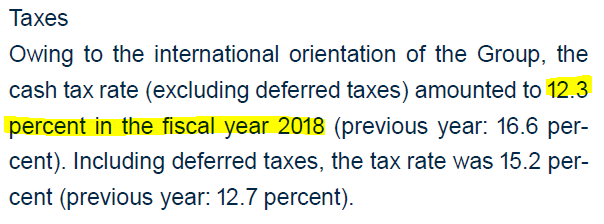

Speaking of globally operating companies brings us to Wirecard AG. This case has been already discussed a lot in our former blog posts HERE, HERE and HERE. Currently, it seems as if Wirecard has massively overstated its business activities in the Asia-Pacific region in its consolidated accounts (whoever was responsible for this) – and hence was in a similar situation as once the Enron management was: What to disclose to the tax authorities? Let’s have a look at the comments on its tax situation in the annual report 2018.

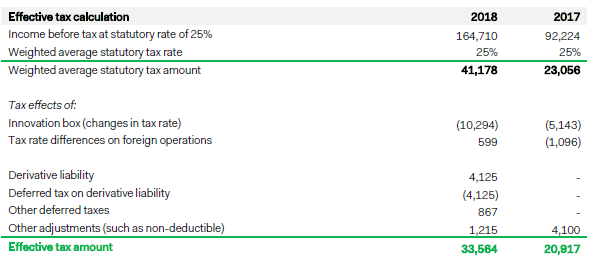

Source: Wirecard AR 2018, p. 183

In the second line, Wirecard shows the expected tax expense based on an income tax rate of 27.025% (the German tax rate). In the third line, Wirecard shows the effects from the effects that foreign tax rates are different from this 27.025% tax rate. Here in both years the effects are positive which means that average effective tax rates abroad must be much lower than the German tax rate.

Calculating the effective average group tax rate based on this information (for reasons of simplicity we exclude all the tax effects listed in the first table above which can be found below the “Divergent statutory tax rates abroad” line), we get to 10.7% in 2018, and 15,1% in 2017. Wirecard gets to slightly higher tax rate results but this is due to some more items included in the calculations.

Source: Wirecard AR 2018, p. 74, own emphasis

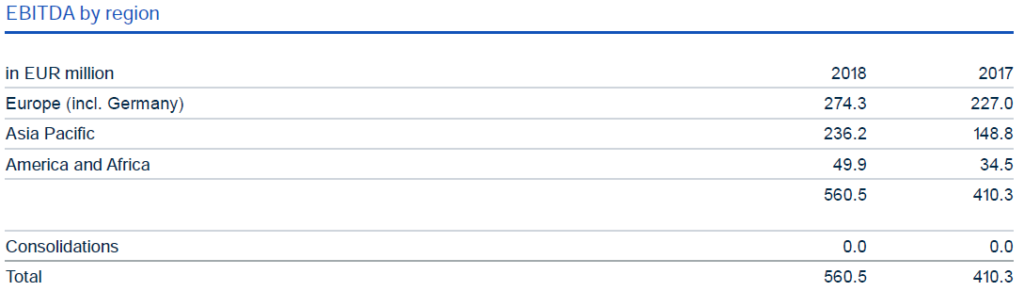

For the further analyses we need Wirecard’s EBITDA split of its business in different regions.

Source: Wirecard AR 2018, p. 194

We do not have a separate split-down to the performance of the pure German business, but we conservatively estimate that in 2018 an EBITDA of roughly 75 to 100 mio Euro, i.e. about 15-20%, relates to operations in Germany. To be fair, this is jut a guess but this would be in line with the still dominant role that the German market played in the European business (Wirecard Bank AG alone generated an EBITDA of roughly 30 mio Euros in 2018).

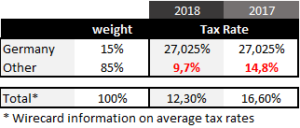

Further assuming that pre-tax earnings roughly show the same regional split as EBITDA (i.e. 15% in Germany, the rest abroad), we can calculate the average tax rate of Wirecard’s foreign business activities. This is the tax rate that leads in the table below to the weighted average group tax rates as disclosed by Wirecard.

It is worth commenting here that the higher the assumed portion of the German business, the lower the average tax rate on operations abroad. I.e. if we assume a weighting of 20% of the German pre-tax profits, we would get to 8.6% (2018) respectively 14.0% (2017) here.

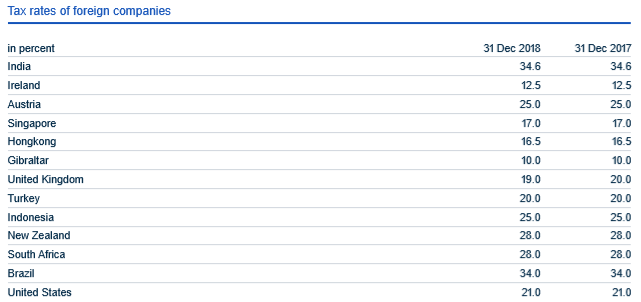

Now let’s have a look at the different tax rates of Wirecard subsidiaries abroad. From the table in the Wirecard annual report (below) we can see that not a single country tax rate – not even the one of Gibraltar – lies below the average tax rate on foreign activities of Wirecard in 2018 (and only Ireland and Gibraltar lie below in 2017).

Source: Wirecard AR 2018, p. 152

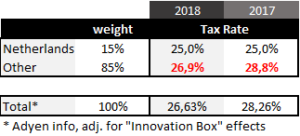

In a next step we have a look at the tax situation of Wirecard’s close peer Adyen N.V. in 2018. The Dutch company follows a similar style of disclosure as Wirecard does – only that the starting point is now a Dutch statutory tax rate.

Source: Adyen AR 2018, p. 83

We can see here that the tax rate differences on foreign operations are relatively small. Adyen states its effective tax rate as 20,38% (2018) respectively 22,40% (2017). However, this downside difference from the statutory tax rate is mainly due to the so called Dutch “Innovation Box” which is a tax incentive scheme for innovative companies in the Netherlands. Excluding the effects from the “Innovation Box” we get to effective tax rates of 26.6% (2018) respectively 28.3% (2017).

The regional split of Adyen’s revenues according to its annual report 2018 was as follows:

Source: Adyen AR 2018, p. 75

Futher assuming that the organisations in the Netherland make about 15% of the business (this is not a super-critical assumption here as Dutch and foreign tax rates are close to each other here anyway) and that pre-tax profit is similarily regionally-distributed as revenues brings us to the following conclusions regarding foreign tax rates. Again, this is a rough estimate as we do not take into account any other tax effects listed in the “Effective tax calculation” table above. But it is the ballpark that is relevant here.

Admittedly, our analysis is based on a couple of simplified assumptions and the two companies Wirecard and Adyen – are not perfectly comparable in terms of regional business split. However, the results are quite remarkable. The effective tax rates in international operations differ massively between Wirecard (10-15%) and Adyen (25-30%).

Summary:

- Wirecards tax rate on foreign operations is very low. In 2018 it was below 10% on an adjusted basis. This is lower than each single corporate tax rate in the countries where Wirecard has foreign operations.

- Reasons for this phenomenon might be certain tax optimisation efforts in foreign countries, although the sheer amount of effective tax rate differnces makes it unlikely that this is the only reason.

- A comparison with close peer Adyen shows that the Dutch company is not able to benefit from such low tax rates abroad, far from it. This again raises the question whether tax optimisation is really at the core of Wirecard’s low tax rates.

- We think that this is a clear sign for at least a quite aggressive revenue recognition in Wirecard’s consolidated accounts. Because of the size of the tax rate differences to the statutory tax rates this might have even been a warning sign for a potential fraud.

Disclaimer: We hold no direct economic stake in Wirecard – in whatsoever direction. We base our analysis on imperfect information and hence we might be wrong with some conclusions. This is just our subjective view and no investment recommendation at all.