During the last days we got a lot of questions about what EY could have seen and what is beyond the detection horizon of regular auditors. This is why we want to shed some more light on Wirecard’s accounting and the proceeding of auditors in this blog post. And we do it by way of the gross revenue accounting approach of Wirecard.

To be clear at the beginning: detecting fraud is not the job of the regular audit. A well-made (or call it whatever you want) outright cheating of companies is not necessarily something auditors of annual financial statements have to uncover. This is rather the job of special forensic investigations – such as the KPMG one (which was only mediocrely successful in our eyes, see HERE). However, routine checks, plausibility analyses and control over the input data delivery process are of course necessary for the job of a regular auditor. But where are the borders of both approaches?

Last Friday, the Financial Times reported that it has information that between 2016 and 2018 EY has not requested any bank confirmations from the OCBC bank in Singapore (where the escrow accounts where before they were transferred to Manila/Philipines in Q4/2020) but rather relied on certifications from the former trustee of these accounts (see HERE). If this is true then it could be indeed a quite problematic auditing proceeding. However, it is not only the treatment of escrow accounts which is at question. In one of our last blog posts we raised concerns about a probably problematic proceeding of EY (and some others did this, too): We commented that for Wirecard applying gross revenue accounting within its Third Party Acquirers (TPA) business it would be necessary to control the ultimate clients. And as – what we know today – many of these ultimate clients presumably do not exist EY should have realised the problems with the Wirecard business model as part of its audit.

We have already discussed the revenue recognition problem of Wirecard’s TPA business in former blog posts (see HERE for a description of the business model of Wirecard, and HERE for a discussion of the revenue recognition problem in the context of KPMG’s special audit). But it is necessary to repeat some points here in order to understand the problem. We mainly focus on IFRS 15 below (which is the IFRS standard for revenue recognition and which is in place since 2018) and hence particularly on Wirecard’s financial year 2018, and not on IAS 18 which was relevant in former years, and which might lead to some slightly different, but not materially different conclusions.

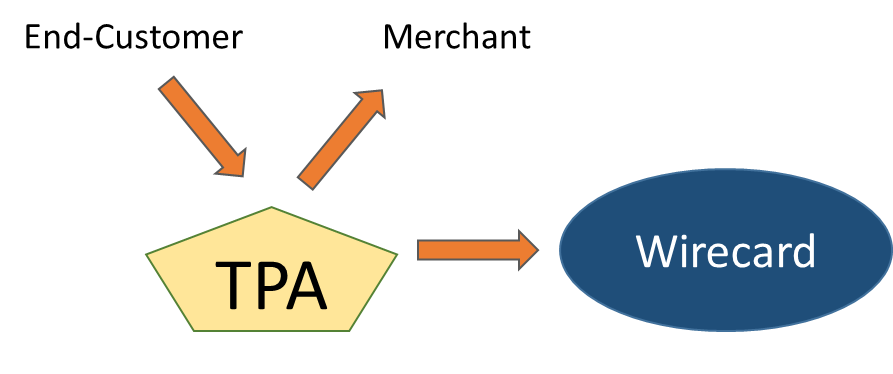

In Wirecard’s TPA business there are mainly three relevant parties for revenue recognition: Wirecard, the TPA and the merchant. The merchant pays for Wirecard’s services which are facilitated by the TPA, or the services that are provided by the TPA but which use some Wirecard input. This little “or” in the last sentence already sets the tone for the further discussions. For revenue recognition of such transactions it is now of utmost importance to understand who is sitting in the driver seat of the transaction: (1) Is it Wirecard because the TPA acts only on behalf Wirecard? (2) Or is it the TPA and Wirecard is only setting the frame for the transactions?

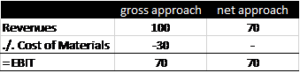

The first case (Wirecard is here the so called ‘principal’) leads to a gross revenue recognition, i.e. Wirecard’s recognition of full processing fees of the transaction as revenues and aditionally the recognition of the commission paid to the TPA as an expense – in the case of Wirecard as ‘cost of materials’. This is also the variant that Wirecard applied in practice. In the second case (Wirecard is here the so called ‘agent’), Wirecard would apply a net revenue accounting, i.e. it would recognise only the net amount that should flow through – processing fee minus commission paid to the TPA – as revenue and then no explicit additional expenses.

Some analysts commented that – while admitting that at the revenue level things look better when following the gross revenue accounting – it is only a minor and not super-material topic because at the EBIT line both variants (gross and net revenue accounting) are equal. But we think differently about this. In fact, it is true that things even out at the EBIT line but the signal to investors is quite a strong one if companies apply gross revenue accounting and this should not be underestimated.

Gross revenue accounting tells investors that Wirecard is controlling the transactions. If the TPA does not perform or similar then Wirecard can perhaps reroute the transactions to other TPAs or other channels. Customer’s (i.e. merchants) would not be directly affected because they would always see only Wirecard as the responsible counterpart, no matter who is acting on behalf of Wirecard to provide the services. This is a very strong statement with regard to stability of the business model and the sustainability of revenue generation.

In contrast, net revenue accounting would tell investors that Wirecard is just setting the frame. It is the TPA who is running the show and customers are aware of this. The quality of Wirecard’s business here would depend more on the good business rapport with the TPA and/or on the direct relationship between Wirecard and the TPA. This would make a much more fragile business model and more risky revenue generation. So, for investors the way of how to do the TPA business revenue recognition has a strong impact on risk assessment and cash flow forecasting.

When determining whether Wirecard is the principal (gross revenue accounting) or the agent (net revenue accounting) the rules of IFRS 15 Revenue Recognition have to be applied. In most practical cases it is quite clear who is in the driver seat – i.e. who is in control of the transaction process. But there are some business models which are somewhere in the twilight zone and where it is not clear whether gross or net revenue accounting is appropriate. This is particularly true for business models that are service-based (such as the one here) rather than product-based: By nature of a service it is the TPA who delivers it to the client but it might still be at Wirecard’s discretion to do it. This is why IFRS 15.B37 contains some indicators on how to detect the controling party in such transactions.

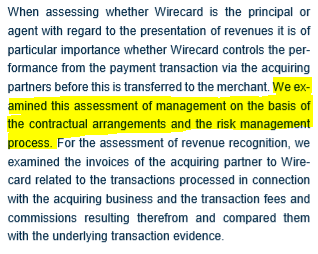

EY describes its proceeding regarding this aspect in its ‘independent auditor’s report’ (which is published as part of the Wirecard annual report 2018) as follows:

Source: Wirecard Annual Report 2018, p. 223 (independent auditor’s report)

Obviously, EY had access to the contractual arrangements – and data from risk management. With these data EY then presumably applied IFRS 15.B37 which allows to check by using 3 major indicators whether Wirecard is the principal or not.

| Indicator | Situation at Wirecard | Check? | Comment |

| Primarily responsible for fullfilling the promise to deliver the goods or services to the customer | This was presumably checked by contracts between Wirecard and TPAs | Yes, must be! | EY has probably not checked contracts beyond the concrete Wirecard-TPA sphere, but we do not know exactly |

| Holding inventory risk | Not applicable for services | X | |

| Discretion to set prices to end-customers | In ranges! Obviously internal data must have indicated also to EY that TPAs have certain discretion, too (see KPMG report, section 1.3.1.1.5) | 50/50 | Difficult to assess who really has the discretion here as both Wirecard (ranges) and TPAs (within ranges) have some price setting abilities. |

So, here we can conclude that EY must have seeen some contracts that indicated that Wirecard is the principal in the TPA business. For EY this was enough to confirm Wirecard’s proceeding.

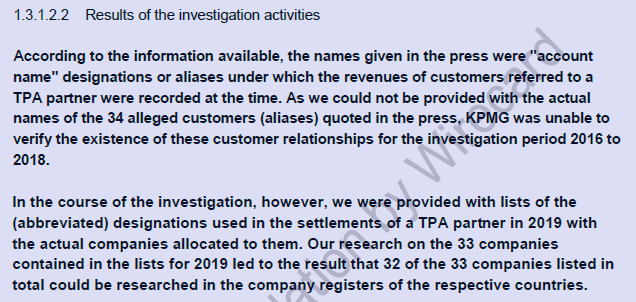

KPMG also analysed this aspect. It also requested contracts – however, not only the Wirecard-TPA contracts but also some contracts between e.g TPAs and merchants – and they were not provided the documents.

Source: KPMG special investigation report, p. 33

For KPMG, the checklist of IFRS 15.B37 should have looked as follows:

| Indicator | Situation at Wirecard | Check? | Comment |

| Primarily responsible for fullfilling the promise to deliver the goods or services to the customer | To be checked by contracts on different levels | No! | KPMG did not get insight into the contracts required, neither could they derive “control of consumer relations” based on actual business practices |

| Holding inventory risk | Not applicable for services | X | |

| Discretion to set prices to end-customers | In ranges! Obviously internal data must have indicated that TPAs have certain discretion, too (see KPMG report, section 1.3.1.1.5) | 50/50 | Difficult to assess who really has the discretion here as both Wirecard (ranges) and TPAs (within ranges) have some price setting abilities. |

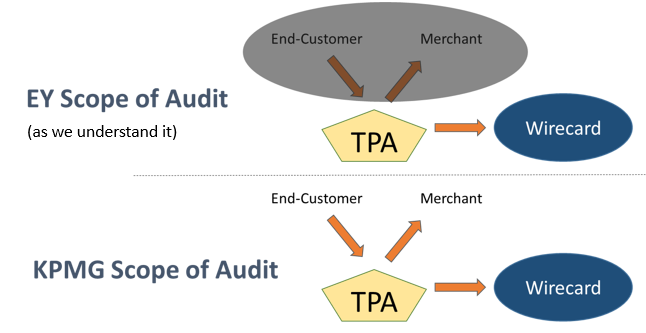

The differences between both approaches lie in the scope of the contractual arrangements checked (as far as we understand it). And this made all the difference here. Of course, this different scopes could be partly explained by the higher standards of a forensic investigation. However, the big question is here where a reasonable border is between both approaches.

Whether the processes and prodecures applied at EY for auditing the TPA revenue accounting were appropriate is impossible to determine here – but of course we give it all the credits as long as we do not know any better. In further analyses, much depends on whether the contractual data they received could be qualified as trustworthy and hence enough to agree with Wirecard’s accounting approach. But we are sure that this case will also have an impact on the general future of IFRS 15 principal/agent accounting and its regular auditing.

Disclaimer: We hold no direct economic stake in Wirecard – in whatsoever direction. And we have no major business relations to neither KPMG nor EY (only that we train staff in business valuation issues from time to time). We base our analysis on imperfect information and hence we might be wrong with some conclusions. This is just our subjective view and no investment recommendation at all.