In one of our former blog posts we had a look at the accounting functioning of equity-settled stock option programs (HERE). Today we want to extend this framework for cash-settled programs – or more concretely: for programs that start out as equity-settled and become cash-settled on the way. It gets a bit more complex, though – but not less interesting.

Starting point is IFRS 2 Share Based Payments: This standard explains that for accounting purposes there is a big difference between equity-settled programs and cash-settled programs. While equity-settled programs, i.e. programs where the beneficiary receives shares of the company as a compensation, are fair-value-measured only once at the grant date – and then not remeasured – cash-settled programs are constantly remeasured until settlement. And there are good reasons for doing this.

Concretely, both equity-settled instruments (IFRS 2.14) as well as cash-settled instruments (IFRS 2.32-33) are initially measured at fair value at grant date. At this date there is no major difference between these two styles of settlement. But now, equity-settled programs leave the entity-sphere directly after granting. The entity owes a certain number of shares depending on certain conditions and perhaps for a certain fixed compensation (the strike). But this liability will not change anymore for equity-settled programs: it still stays the same number of shares – assuming a plain vanilla program. All economic changes to this promise – i.e. share price movements – take place outside of the entity’s sphere (at the capital market where the shares are traded). It might be that the company is covered (already owns the expected number of shares to give) or plans to go for a capital raising in the future or plans to buy-back shares from the market later. But the concrete way does not matter here, these are all transactions with the capital market, and hence they do not play a role in the entity-focused IFRS understanding.

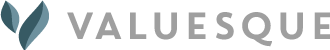

Cash-settled instruments, in contrast, are not left at their grant date value until settlement. In the case of cash-settlement the entity has a cash-liability to pay – and the amount of payment might change over time, depending on the value of the underlying shares. This is a big difference to equity-settled instruments: While in the equity-settled case the company owes a fixed number of shares (plain vanilla case) that does not change over time, in the cash-settled case the company owes a variable amount of money, an amount that will change over time depending on stock price changes until settlement. And as – again – IFRS is an entity accounting system, the liability in the cash-settled case has to be remeasured constantly depending on market dynamics (IFRS 2.30). The following graph highlights the different treatment of equity- and cash-settled schemes according to IFRS 2.

Now one might ask: ‘Where is the difference in economic terms? Existing shareholders will end up with the same consequences in both cases – tax issues aside. Either the entity has to deliver the shares at a certain value at settlement or the cash-equivalent of this. This should not matter.’

And this is even correct! As seen from the shareholders’ position the consequences are the same. But – again and again – IFRS is not a shareholder perspective accounting system, it is an entity-focussed accounting system. And on the entity level things are quite different.

This is an important point to consider when e.g. valuing ownership positions in a company (e.g. when determining the fair value of shares): For equity-settled instruments it might be necessary to do certain adjustments to the accounting set of information simply because we cannot fully rely on an entity-based accounting system if we want to determine shareholder positions. And this is not due to a bias in reporting, it is just because we now take a different perspective than the reporting system does.

But let’s stick to IFRS accounting here. In terms of P&L impact over the full time-span between grant and settlement the equity-settled instrument obviously carries a higher total expense if the value of shares decreases over time, and it carries a lower total expense if the shares increase over time (this is admittedly a simplified view as time value effects of option pricing usually leads to slightly different break-even points). Of course, you never know before in which direction share prices develop. But for a company in a growth stage with a sound business model it at least seems to be the ex-ante smarter way to focus on equity-settled instruments – if management has the P&L expense in mind.

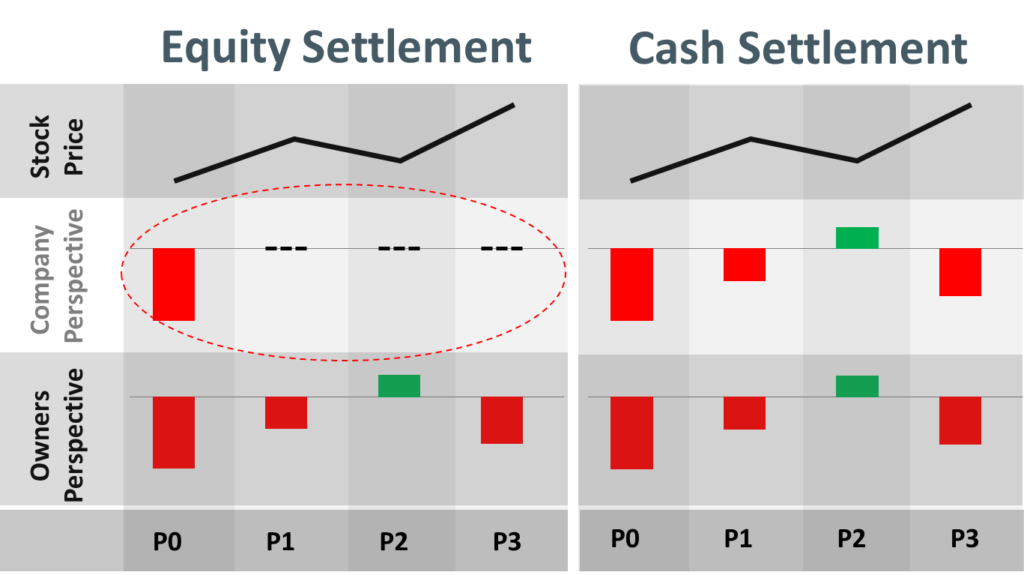

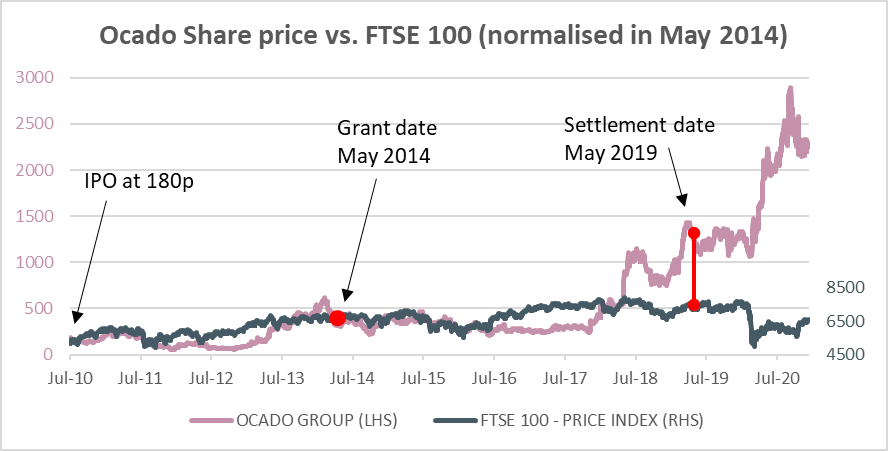

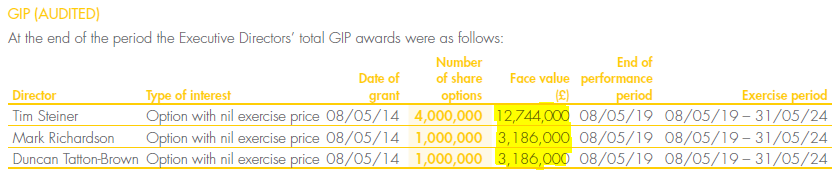

This brings us back to Ocado Group Plc. The company is a UK-based online grocer without any own stores. Founded in 2000 by three former investment bankers, it IPOd in July 2010. While already running several management incentive schemes, the company set up an additional incentive program in May 2014, the five-year (expiration on 8 May 2019) so called Growth Incentive Plan (GIP). This plan consisted of options with a zero strike and was subject to a single performance condition, the share price growth of Ocado relative to the growth of the FTSE 100 Share Index over that same period.

Source: Ocado AR 2014, p. 122.

We do not know what exactly the original plans of Ocado were in 2014 (the time when they set up the incentive program under analysis here). But at least at time of settlement the company found an interesting way of not making the GIP program impact the profit & loss statement too much. But step by step: Originally, the plan was set up as an equity-settled instrument with all the accounting consequences thereof. But then in the 2019 annual report we could read the following.

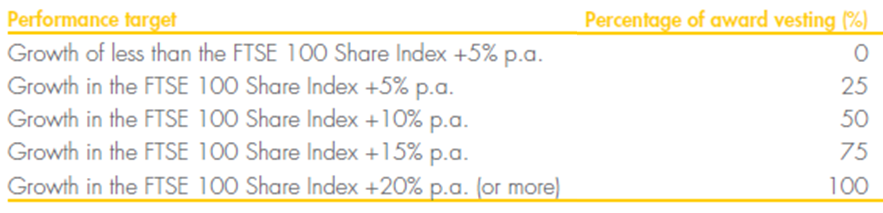

Source: Ocado AR 2019, p. 124, own emphasis.

Footnote 4 is important but difficult to read here. We rewrite it below (Ocado AR 2019, p. 124):

“(4) The nil cost options were exercised on 23 May 2019 at an option price of £12.402 with a total gain of £80,240,940 (lower than the figures presented in the single figure table). On the basis of the Directors’ intention to sell on exercise, in the interests of all stakeholders, the Committee decided to pay the gains in cash as permitted under the GIP scheme rules.”

Hence, Ocado cash-settled the originally equity-settled options at a value of 80.24 mio GBP. What exactly here ‘in the interest of all stakeholders’ means is at least unclear. In particular the question of why shareholders and other stakeholders should welcome the ‘directors’ intention to sell on exercise’-comment is a tricky, here not covered governance topic.

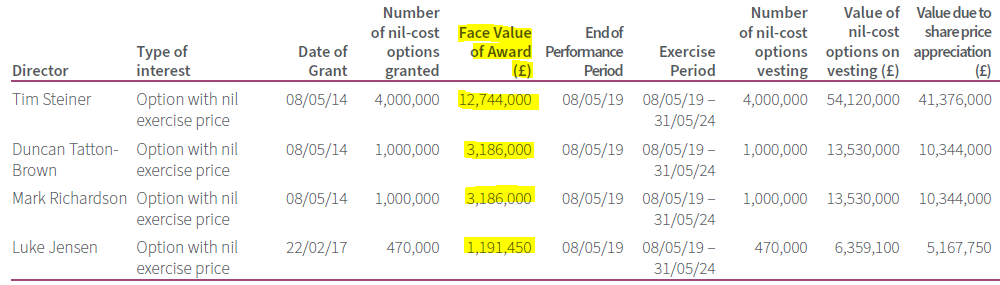

The table above also highlights the ‘value due to share price appreciation’ (very right column). This is the change in the instruments since grant date.

Looking at the Ocado share price development compared to the FTSE 100 between 2014 and 2019 (equalized at the grant date in the graph) it is not a big surprise that ‘share price appreciation’ is the main part of the value contribution.

Source: Ocado AR 2014, p. 121, own emphasis.

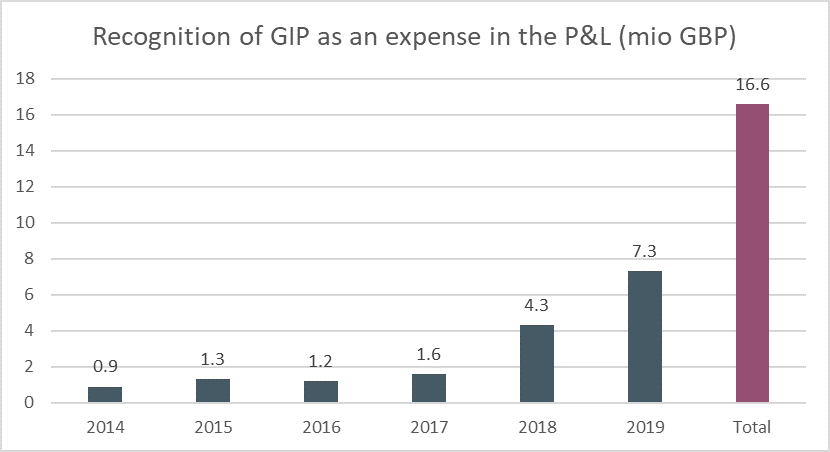

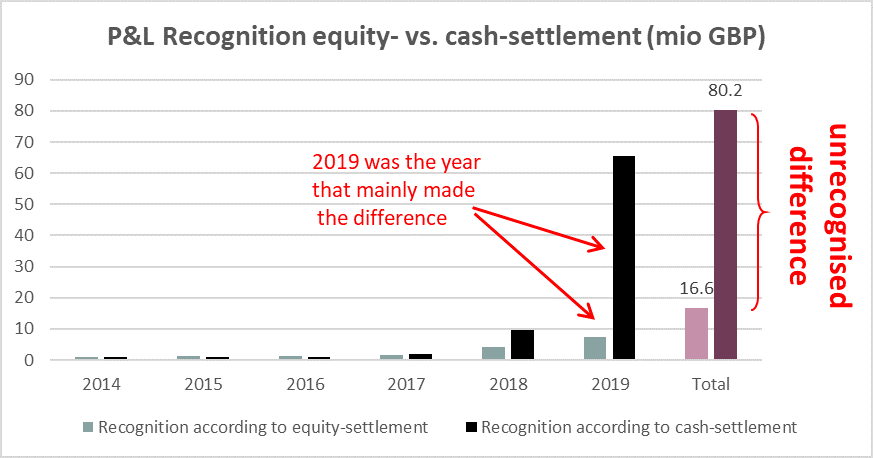

Now, one thing is clear. If Ocado had structured the plan with a cash-settlement already at initiation of the scheme, the company would have had to expense the full 80.24 mio GBP through the P&L. Now as they switched horses at the end of the race, they don’t do it, they only recognise 16.6 mio GBP between 2014 and 2019 – which also falls short of the 20.31 mio GBP face value of the total GIP program (see table above).

Source: Ocado ARs

Anyway, the steepening-up of actual P&L expense allocations over time is because the ‘expectation of meeting the performance criteria was taken into account when calculating this expense’ (Source: Ocado ARs) and the probability of meeting these criteria increased over time with the increasing Ocado share price. (It is worth noting that Ocado even in 2019 took the probability of meeting the performance criteria into account for the valuation, see AR 2019, p. 200; this does not make a lot of sense as the program ran out in May 2019 with a clear result: 100% vesting!).

Below we have rebuilt – roughly – a comparison of the actual P&L expense vs. the P&L expense if the company had already qualified the program as cash-settled at initiation. The concrete numbers might differ a bit as we do not have all the numbers available, but in total this should provide a good picture of what the relations are. It is striking that it is particularly the year 2019 that makes most of the difference because in the first months of 2019 a) the Ocado stock price rose quite strongly and b) the probabilities of full vesting (against the benchmark of FTSE + 20% p.a.) stepped up to 100%.

This all looks at the very least like a quite unlucky accounting behaviour. But we are also not really sure whether this is within the rules of IFRS. The ‘Guidance on Implementing IFRS 2 Share-based Payment’ (this guidance accompanies, but is not part of, IFRS 2) shows an example for such a switch from equity-settlement to cash-settlement (example 9 in the guidance). But this example is made for the case that the share price DECREASE over time. In this example, the company should still stick to its original relatively high expense based on equity-settled scheme in the year of change, and then explicitly show the benefit of the now lower built-up liability in the consequent years to map the lower expected settlement costs.

However, in the Ocado case it is an INCREASE in share prices that lays the basis of the accounting treatment. And additionally there are no further periods anymore where any changes in the liability could be accounted for (as the change was made in 2019, basically at settlement). The guidance example explicitly refers to IFRS 2.27 (“The entity shall recognise, as a minimum, the services received measured at the grant date fair value…”) which is admittedly not violated by Ocado here – the minimum expenses are recognised. But even some auditing firms (see e.g. KPMG 2018, Share based payments, IFRS 2 handbook, available HERE, p. 191f.) express doubts that this is the best proceeding. With a view on the ‘fair presentation’ requirements of IAS 1 we are in doubt about this proceeding, too.

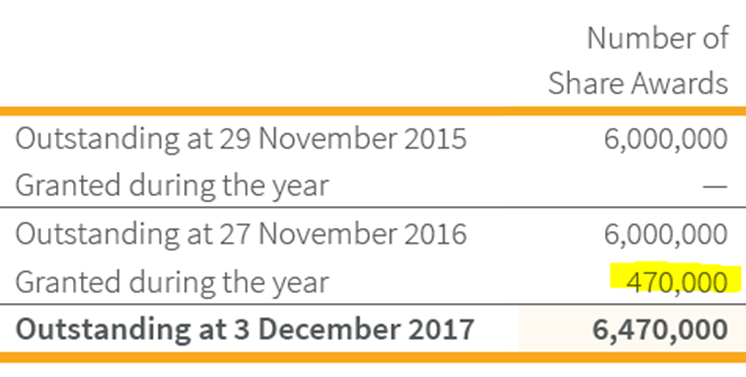

Four more comments are necessary here. For the first one we have to go back to 2017. In this year the company reported as part of the ‘Directors’ Remuneration Report’: “Granted: No awards under the GIP were granted during the period.” (AR 2017, p. 101), only to show several pages later the following GIP-related graph:

Source: Ocado AR 2017, p. 172, own emphasis. Important, this is not a calendar mismatch (i.e. not due to 27 November 2016 to 31 December 2016 not covered in the table), as also in the 2016 annual report it is made clear: “Granted: No awards under the GIP were granted during the period.”, AR 2016, p. 108)

It was impossible to find out from the 2017 AR how this discrepancy of 470,000 shares can be explained. Only later in the 2018 AR we learned that the 470,000 shares were awarded to Luke Jensen, who was at financial year end 2017 only the upcoming CEO Ocado Solutions (starting 1 March 2018) and hence not a ‘director’ at the time of the AR 2017 date. This is why the shares were not mentioned in the directors’ remuneration report of 2017. He was an exception for the GIP because he got awarded the share awards before he became a director. It would have been nice if this important tweak of the GIP had been explained already in the 2017 AR. There were no reasons to hide it (we are not aware of whether the company explained this verbally at some occasions). It would have prevented a lot of confusion on the Ocado incentive plans at that time.

Second, Ocado’ accounting treatment also benefited from the fact that recent amendments to IFRS 2 have only dealt with similar situations but not the concrete Ocado situation. E.g., on 20 June 2016, the IASB published an amendment to IFRS where they clarified the accounting consequences of vesting conditions for cash-settled programs, the classification of share-based programs with a net settlement feature (i.e. where the company withholds part of the shares to settle the tax duties arising of this program) and the treatment of programs that change from cash-settlement to equity settlement due to some modifications in terms and conditions. But changes from equity-settlement to cash-settlement were not addressed in this amendment paper.

Third, we still struggle to understand why the sum of P&L expenses amounts to only 16.6 mio GBP while the face value of instruments is 20.3 mio GBP (see table below). None of the instruments have been cancelled and vesting was at 100% (even for the Luke Jensen part). We have no clue where the difference of 3.7 mio GBP got lost here.

Source: Ocado AR 2019, p. 124, own emphasis.

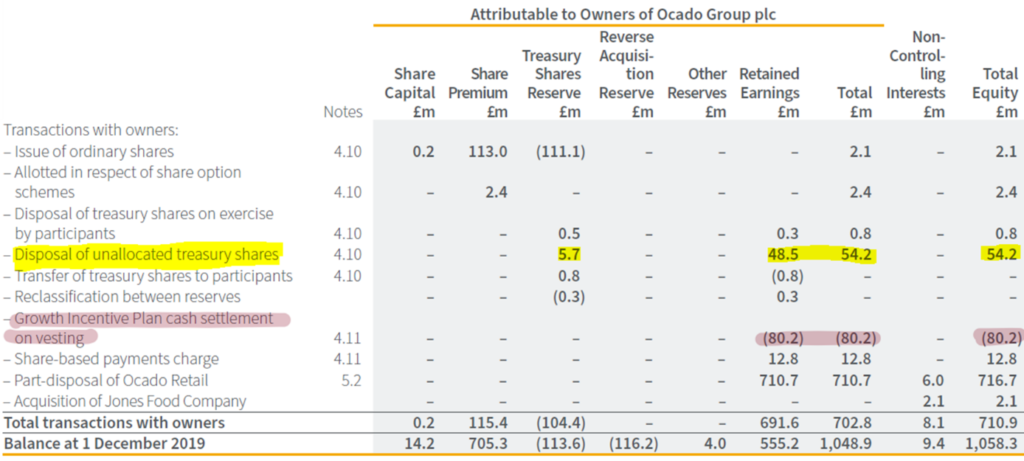

And fourth: Some market observers stated that the 2019 GIP settlement has been ‘trued-up’ (i.e. backed by market transactions) at least partially by selling treasury shares in the amount of 54.2 mio GBP in 2019 (see the excerpt from the change-in-equity account below). However, we also have doubts that this is the case.

Source: Ocado AR 2019, p. 14, own emphasis (yellow: disposal of treasury shares, red: cash payment from the incentive plan)

The here relevant ‘unallocated treasury shares’ are related to the company’s ‘treasury share reserve’ (see the link ‘4.10’ in the table above). This reserve, however, according to the comments in the annual report 2019 (p. 194) relates to two different incentive programs of the company, the ‘JSOS’ (Joint Share Ownership Scheme) and the ‘VCP’ (Value Creation Plan) – important to note that Ocado clearly separates the disclosure for the seven different schemes JSOS, VCP, GIP, ESOS (Executive Share Ownership Scheme), LTIP (Long Term Incentive Plan), SIP (Share Incentive Plan) and SAYE (the so called Sharesave Scheme). The here relevant JSOS and VCP schemes’ treasury shares are managed by trustees, i.e. not the company itself. Furthermore, the wording ‘unallocated’ does NOT mean that the treasury shares are NOT related to the JSOS plan (and hence perhaps relate to the GIP plan). In fact, they still relate to JSOS as is explained on page 198 of the 2019 annual report in section ‘4.11 Share Options and Other Equity Instruments, (b) JSOS’ (“Of these ordinary shares, 735,557 (2018: 4,516,292) are held by the Employee Benefit Trust on an unallocated basis.”). We think it is unlikely that the trustees of a different (JSOS) plan should serve for a truing-up for the GIP plan. This is not what trustees are allowed to do.

What could be an explanation for this proceeding is that Ocado jumps around in the wording of JSOS, i.e. that in the context of treasury shares JSOS does not only relate to the one particular JSOS scheme but rather as an umbrella term for all incentive schemes. But then, it is a) bad disclosure, b) still the true-up is only a part of the 80.2 mio GBP payment and c) expenses still do not show up in the P&L. Important: This is only a hypothetical explanation of what was going on in 2019 at Ocado. According to the wording in the annual report it is rather unlikely that this is the case.

This fourth comment should also serve as a reminder that it is usually very difficult to understand the management remuneration system of companies in total. With so many different schemes an analyst really has to take care – in particularly for corporate governance reasons – what is awarded under which scheme and how this relates to management incentives. Without going deep into the single schemes investors cannot prevent to get surprised by wrong management incentives and hence sometimes wrong management decisions.

Disclaimer: We hold no economic stake in Ocado – in whatsoever direction. We base our analysis on imperfect information and hence we might be wrong with some conclusions. This is just our subjective view and no investment recommendation at all!