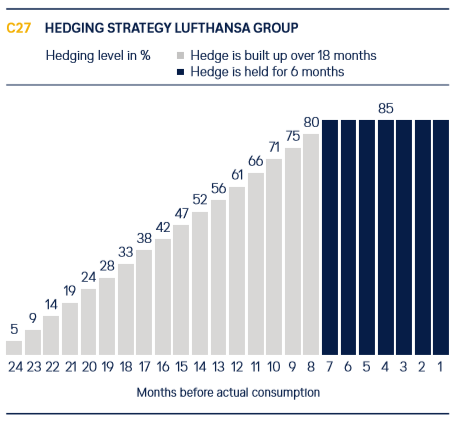

No matter whether it is about currencies or commodities: operating hedging requires two big decisions. First decision: how much volume do we want to hedge? This starts with the most straightforward strategy of only hedging what is sold or bought (but where payment is later), but often goes much further. Companies anticipate that they will also sell products, buy raw materials, etc. in the future, and therefore in many cases already hedge in expectation of future business activities. This is called “anticipatory hedging”. As companies do not know exactly how much they will sell or buy, they usually leave some future expected volumes open and gradually increase the hedging levels over time (as confidence about real volumes increases). As an example we show the anticipatory fuel cost hedging strategy of Deutsche Lufthansa AG which runs 24 months ahead of actual transactions.

Source: Deutsche Lufthansa AG, AR 2019, p. 72.

Second decision: do we want to fix prices the hard way or do we want to still benefit from price movements in our favour in the future? Of course, the second variant sounds much more attractive but this is also the much more expensive one. While the hard fixing involves relatively cheap futures or forward transactions, the flexible approach usually requires the use of costly options. In terms of flexibility, there is of course not only black and white. Companies can stay flexible within certain price ranges, or up to a certain level, or…. Every degree of flexibility can be built just by combination of different derivatives. However, in reality we often see that companies rather go for the hard-fixing (not always, not fully, but in tendency). The reason for this is that still in many financial departments hard costs are such a sensitive topic, and option costs are hard cost whereas forgone attractive prices (that is what companies suffer if they are on the wrong side of a forward/futures-based trade) are not.

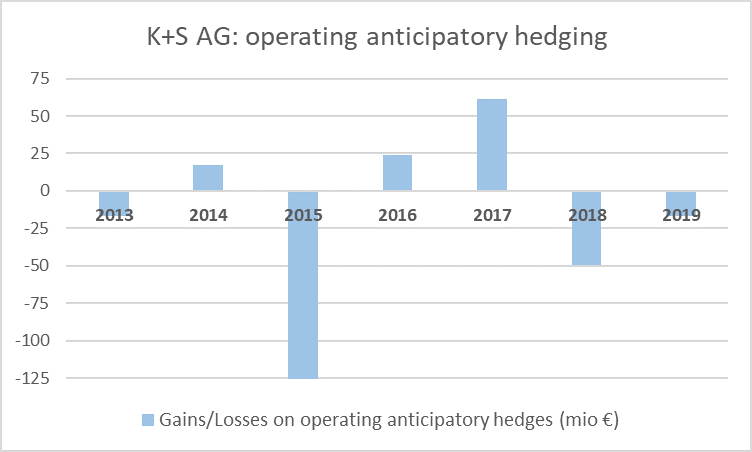

Regular movements in K+S anticipatory hedging portfolio

Anyway, in an ideal world, companies stay a little bit underhedged or are perfectly hedged, and hence there are no uncovered hedging positions left once the transaction is settled. However, in reality sometimes companies do not want to stay on the safe side and deliberately take some risk of being left with uncovered positions, only to early lock-in prices. E.g. the German chemical company K+S AG has been following this strategy for already a long time. The company writes: “…we enter into hedging transactions for future business, which can be anticipated with a high level of probability based on empirically reliable findings (anticipatory hedges).” (Source: K+S, Annual Report 2018, p. 111) Hedging of K+S mainly relates to covering future revenues in USD and futures expenses in CAD. Due to their high level of hedging, K+S regularly faces overhedging. As exchange rates can move in favour or against K+S between hedging and settlement, the net effect from overhedging can be positive or negative for K+S. The following graph shows the development of gains and losses on operating anticipatory hedges of K+S over time.

This graph shows an interesting finding: Overhedging is not always a bad thing. And even for companies that do not have high hedging levels in advance it sometimes works as a softener to a weakening core business. E.g., in the years directly after the 2008 financial crisis there were lots of companies which benefited from exchange rate movements due to empty hedge contracts that had to be unwound. German car maker Daimler AG, for example, could record massive gains from selling GBP-hedges in 2009, just after the GBP has lost more than 20% since the middle of 2007.

Overhedging effects at European Airlines 2020 (and beyond)

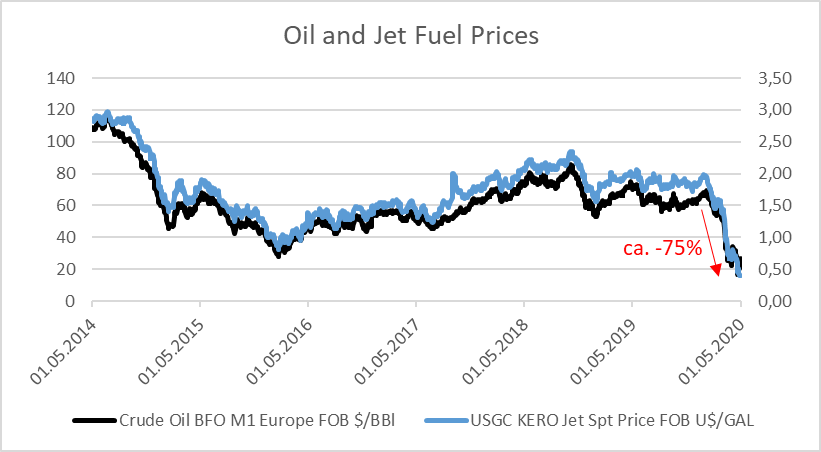

But this is nothing companies can count on. During the financial crisis there were also many companies which suffered from a double whammy: low revenues AND losses on overhedges. In fact, overhedging is always a risk factor if it is the result of a volume-breakdown, such as during the financial crisis or currently in the coronavirus-crisis. Let’s have a look at airlines’ fuel hedging activities during the current coronavirus-crisis which clearly resulted in overhedging due to the massive recent flight cancellations and which were accompanied by the sudden and strong oil price decrease.

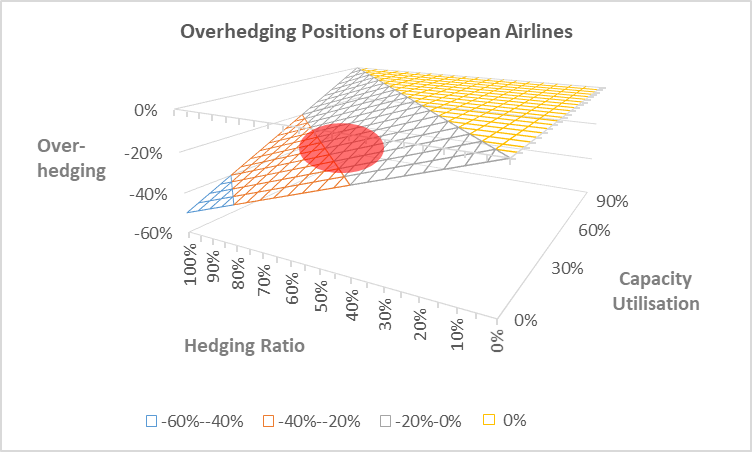

For airlines the overhedging effect is particularly high if a) already a lot of anticipated volume is hedged, such as in the case of Ryanair or IAG, and/or b) high prices are locked-in, such as in the case of Lufthansa and EasyJet (attention: information about the affected companies is informal information). The following graph shows our assumed overhedging position area (red oval) for most European Airlines for 2020.

Comparing volume hedge levels with actual capacity utilisation, and hedged prices with actual spot prices we get to a hedging loss in 2020 which amounts – on average – to roughly 4-5% of total costs base before hedging losses. However, differences for single airlines are quite material in our calculation.

With the experience of the financial crisis 2008, we further think the room for renegotiation, rolling over, etc. of hedging contracts – in order to not leave too many hedging contracts stranded – is usually limited for companies (but we do not know this exactly). Hence, we do not think that airlines come out of this overhedge-topic much better than we have described it here.

In this whole context it is, however, also worth mentioning that the current price distortions are not only bad for European airlines. The low jet fuel prices are also a chance for locking-in now cheap prices for the future. However, investors have to be careful with this „new hedging“. So far it is not at all clear how long airlines have to live with materially lower capacity utilisation. Hence, while prices are cheap, there is risk of still overhedging for the future.

Business Flexibility and the Fixed/Variable Cost Question

In terms of general risk assessment of airlines there is another interesting point to watch for: The impact of hedging on business flexibility (for a general assessment of business flexibility in times of coronavirus, see HERE). Fuel costs have always been a strange animal in the cost-circus of airlines. While in theory they should be a typical variable cost, in practice they are not – or only a bit. And there are several reasons for this. The first one is that airlines have not always been able or willing to pass them through. There were times of increasing jet fuel prices at which it was more important for airlines to protect airport slots or to gain market share. And there were times in some local markets – in particular following the bankruptcy of an airline or some M&A consolidation, i.e. when competition decreased – where airlines could keep their pricing level even against the background of decreasing fuel costs. And historically pricing power was also business model dependent. Usually legacy carriers have better possibilities than low-cost carriers to pass-through increasing fuel prices or not passing through decreasing fuel prices, simply as premium passenger demand is less price elastic.

The second reason is that due to fuel price hedging activities airlines have a lagged P&L reaction to fuel market price movements. This also restricts flexibility of companies (but of course at the benefit of being better able to plan costs). The consequence of both is that even in a normal environment in our calculation effectively only ca. 65%-85% of fuel costs can really be seen as more or less variable.

But now things get even worse. For overhedged fuel positions there is no revenue standing against them. They are hard costs anyway, and this means: fixed costs. As there are also some volumes hedged for the years beyond 2020 (although less than for 2020, see the Lufthansa hedging strategy above as an example) this fixed cost effect will not be a one-time effect. We will also see some of it at least in 2021.

Airlines are only the obvious ones, more to come from other companies in Q2/2020

Of course, airlines – with their massive loss in volumes and the simultaneous strong reduction in oil prices – are the obvious first victims of overhedging effects of the coronavirus-crisis. But this does not mean that they are the only ones. For many industries the full cut in volumes (both on the revenue as well as on the cost side) will only be seen starting in Q2/2020. So we expect that there will be more companies that will disclose some overhedging effects in the future – probably mainly based on currency hedges. As already stated, these effects can be positive or negative – depending on the concrete currencies and positions. So be prepared for this. However, we also have to state that we do not expect lots of material overhedging effects – but in some cases they will still be non-negligible.

Next years will see more option-based hedging (and less forward/futures-based hedging)

And finally, there is also a nice lesson from history: Whenever companies got cought on the wrong foot with their „cheap“ hedging strategy they think about switching instruments for the future (i.e. more options, less forwards/futures) which allows them to be more flexible and benefit more from both directions of price developments. This has been the case with many financial institutions which once – in highest trouble and facing insolvency threats – hedged their equity investment portfolio in late 2002, early 2003 „at low cost“ (i.e. using forwards and futures), only to wake up a couple of months later and seeing the stock market rallye takes place without them.

And this is also what we are going to see in the coming months. Vanessa Hudson, CFO of Australia’s Quantas Airways Ltd., gives a foretaste: “We are thinking around how to structure our hedge profile to ensure that we’ve got both our participation (in a price fall) but protection as well from a higher fuel price.“ and „Because what we’ve seen in the past is that when demand returns and recovers, that fuel price most likely will increase. So we are staying flexible and thinking about both sides of the recovery process.” (both quotes: Reuters, 23 March 2020).